Why a new approach is needed

1. There is an urgent need to transform the health and care system. We need to move to a neighbourhood health service that will deliver more care at home or closer to home, improve people’s access, experience and outcomes, and ensure the sustainability of health and social care delivery. More people are living with multiple and more complex problems, and as highlighted by Lord Darzi, the absolute and relative proportion of our lives spent in ill-health has increased.

2. Addressing these issues requires an integrated response from all parts of the health and care system. Currently, too many people experience fragmentation, poor communication and siloed working, resulting in delays, duplication, waste and suboptimal care. It is also frustrating for people working in health and social care.

3. Neighbourhood health reinforces a new way of working for the NHS, local government, social care and their partners, where integrated working is the norm and not the exception. Some places have already made progress in developing an integrated local approach to NHS and social care delivery. The full vision for the health system will be set out in the 10 Year Health Plan, including proposals to help make this emerging vision for neighbourhood health a reality, informed by existing work and public, staff and stakeholder engagement.

4. This document sets out guidelines to help integrated care boards (ICBs), local authorities and health and care providers continue to progress neighbourhood health in 2025/26 in advance of the publication of the 10 Year Health Plan. The appendix provides more specificity around the initial 6 components of neighbourhood health to create a common understanding of what lies at its core, but the guidelines are deliberately short and permissive about how neighbourhood health should be implemented, setting out a framework for action that can be tailored to local needs.

5. Neighbourhood health aims to create healthier communities, helping people of all ages live healthy, active and independent lives for as long as possible while improving their experience of health and social care, and increasing their agency in managing their own care. This will be achieved by better connecting and optimising health and care resource through 3 key shifts at the core of the government’s health mission:

- from hospital to community – providing better care close to or in people’s own homes, helping them to maintain their independence for as long as possible, only using hospitals when it is clinically necessary for their care

- from treatment to prevention – promoting health literacy, supporting early intervention and reducing health deterioration or avoidable exacerbations of ill health

- from analogue to digital – greater use of digital infrastructure and solutions to improve care

The plan to reform elective care is an example of this commitment in action, improving experience and convenience by providing more direct access to tests, scans and surgery in dedicated local centres and empowering people with more choice over when and where they will be treated, including through the NHS app.

6. All parts of the health and care system – primary care, social care, community health, mental health, acute, and wider system partners – will need to work closely together to support people’s needs more systematically, building on existing cross-team working, such as primary care networks, provider collaboratives and collaboration with the voluntary, community, faith and social enterprise (VCFSE) sector. In some parts of the country this is already happening, and much can be learned from these experiences. System* leaders will need to work with partners across local communities, together creating a collaborative high-support, high-challenge culture, to develop a shared vision and outcomes, define population boundaries for neighbourhood health and introduce joint accountability arrangements.

* Use of the term “system” in this publication refers to integrated care system.

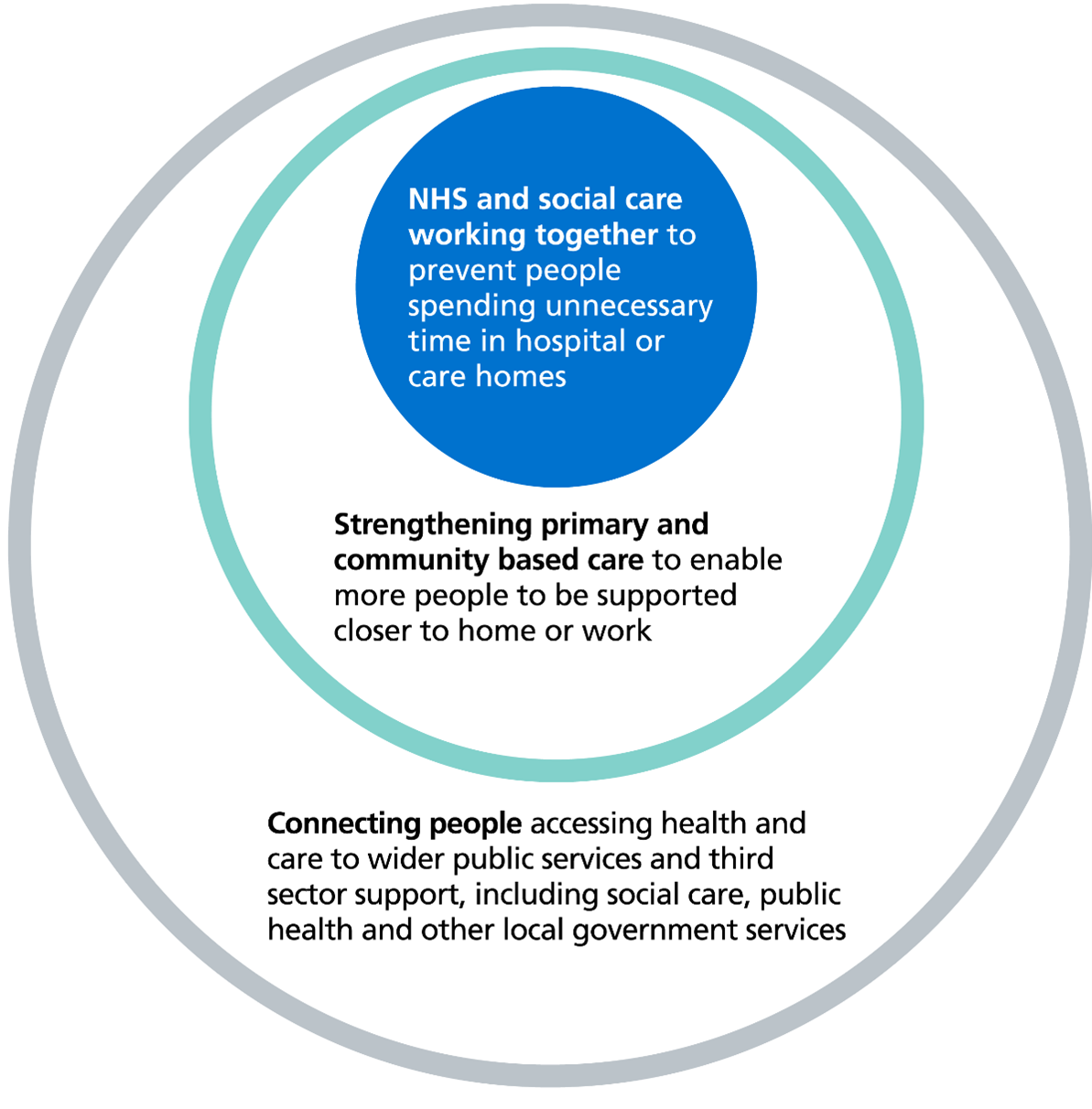

7. In the coming months, drawing on learnings from existing work, the focus will be on creating the national and local conditions for different ways of working. The diagram below shows the aims for all neighbourhoods over the next 5 to 10 years. For 2025/26, through the standardisation and scaling of the initial 6 components, we are asking systems to focus on the innermost circle to prevent people spending unnecessary time in hospital and care homes. As core relationships between the local partners grow stronger, we expect systems to focus increasingly on the outer circles. This will involve exploring their own ways of building or reinforcing links with wider public services, the third sector and local communities to fully transform the delivery of health and social care according to local needs:

Diagram showing the aims for all neighbourhoods over the next 5 to 10 years

Image text:

- NHS and social care working together to prevent people spending unnecessary time in hospital or care homes.

- Strengthening primary and community based care to enable more people to be supported closer to home or work.

- Connecting people accessing health and care to wider public services and third sector support, including social care, public health and other local government services.

Neighbourhood health is an important part of wider public sector reform. Previous estimates suggest around 1 in 5 GP appointments are taken up for non-medical reasons, such as loneliness or to seek advice on housing or debts. A less complex and simpler connection between health and wider local public services, as depicted in the outer circle of the diagram, has the potential to improve outcomes for people and wider public sector productivity, and to reduce pressure on GP surgeries, emergency departments, acute hospital services and providers of long-term social care. It is an opportunity to enhance the partnership between councils, local public agencies like job centres, the third sector and NHS partners, and to design much clearer pathways for non-medical support from the local public and third sectors.

8. NHS England regional teams, working with local government partners and informed by the evidence generated from existing work in systems, should work with systems to agree locally what specific impacts they will seek to achieve during 2025/26. We expect these to include, as a minimum, improving timely access to general practice and urgent and emergency care, preventing long and costly admissions to hospital and preventing avoidable long-term admissions to residential or nursing care homes.

9. This document provides further guidelines on neighbourhood health. These draw together key points from earlier guidance and build on existing local best practice. It should be read alongside the 2025/26 NHS operational planning guidance and 2025 to 2026 Better Care Fund policy framework, so systems can make progress against the above aims in advance of the publication of the 10 Year Health Plan.

Making a start on delivery

10. Many local organisations across England have collaborated over the past few years to develop great examples of one or more of the individual components that make up an effective neighbourhood health service. Many of these best practice examples have informed the development of national policy or guidance, including the Fuller Stocktake and Intermediate care framework. The priority now is to connect those components and implement them system-wide, starting with frontline services for people with the most complex health and care needs.

11. While 2025/26 will be a challenging financial year for the NHS, local government and social care, the coming months offer a significant opportunity to build on current momentum for a neighbourhood health approach in order to ensure the ongoing sustainability of health and social care delivery. Systems are asked to do this by:

- standardising 6 core components of existing practice to achieve greater consistency of approach

- bringing together the different components into an integrated service offer to improve coordination and quality of care, with a focus on people with the most complex needs

- scaling up to enable more widespread adoption

- rigorously evaluating the impact of these actions, ways of working and enablers both in terms of outcomes for local people and effective use of public money

This will set the foundations for scaling and expanding the neighbourhood approach over the coming years.

12. The focus in 2025/26 should be supporting adults, children and young people with complex health and social care needs who require support from multiple services and organisations. This cohort has been estimated at around 7% of the population and associated with around 46% of hospital costs, according to NHS England analysis from adapted Bridges to Health data. It is likely that systems will initially prioritise specific groups within this cohort where there is the greatest potential to improve levels of independence and reduce reliance on hospital care and long-term residential or nursing home care, both improving outcomes and freeing up resources so systems can go further on prevention and early intervention. This approach is likely to focus on around 2% to 4% of the population. Examples of population cohorts with complex needs include:

- adults with moderate or severe frailty (physical frailty or cognitive frailty, for example, dementia)

- people of all ages with palliative care or end of life care needs

- adults with complex physical disabilities or multiple long-term health conditions

- children and young people who need wider input, including specialist paediatric expertise into their physical and mental health and wellbeing

- people of all ages with high intensity use of emergency departments

13. Increasing coordination, consistency and scale in delivering health and social care to specific sub-cohorts should result in the following benefits over time:

- avoiding or slowing health deterioration, preventing complications and the onset of additional conditions, and maximising recovery whenever possible to increase healthy years of life

- streamlining access to the right care at the right time, including continued focus on access to general practice and more responsive and accessible follow-up care enabled through remote monitoring and digital support for patient-initiated follow-up

- maximising the use of community services so that better care is provided close to or in people’s own homes

- reducing emergency department attendances and hospital admissions, and where a hospital stay is needed, reducing the amount of time spent away from home and the likelihood of being readmitted to hospital

- reducing avoidable long-term admissions to residential or nursing care homes

- reducing health inequalities, supporting equity of access and consistency of service provision

- improving people’s experience of care, including through increased agency to manage and improve their own health and wellbeing

- improving staff experience

- connecting communities and making optimal use of wider public services, including those provided by the VCFSE sector

14. Evidence from services and research has identified elements of partnership working that are critical for effective implementation of neighbourhood health:

- a mechanism for joint senior leadership, such as a joint neighbourhood health taskforce, in each place to drive integrated working, comprising senior leaders from the constituent organisations across health and care, including the acute hospital

- a collaborative high-support, high-challenge culture, which fosters strong relationships between all system partners, including the NHS, local government, social care providers and the VCFSE sector. This culture is supported by shared values, outcomes, clear lines of accountability and definitions for how services are organised at place and neighbourhood level (aligning service delivery across organisations to agreed populations at these levels)

- visible clinical and professional leadership and management, at both system and place level, supported through the effective clinical and care professional leadership framework. This includes working in partnership with communities (including people and carers* with lived experience and local third sector organisations) to co-develop neighbourhood health locally, and to mobilise change

- effective processes (including communication channels, IT systems and information governance processes) and training and workforce development to enable collaborative working

- making best use of all funding arrangements, including those that are formally pooled, to facilitate partnership working

* Wherever “carer” is used in this publication, it refers to both paid and unpaid carers, however there are key differences between the two. Unlike paid carers (professionals either employed by the individual receiving care, or via NHS or local authority funding or services), unpaid carers can be anyone – including children – who look after a family member, partner or friend who cannot cope without their support. The Care Act 2014 requires local authorities to assess, provide support and promote the wellbeing of unpaid carers.

15. Learning from work in 2025/26, alongside emerging research and innovation, will inform the future development of the neighbourhood health and care model as it extends to other population cohorts. This learning will also shape support offers to systems, and a more formal evaluation framework for the future delivery of neighbourhood health systems will be developed. We now ask systems to:

- consider how they will evaluate the impact of the changes they make in a systematic, consistent and scalable way to build the case for future expansion and link to the triple aim of improving population health outcomes, people’s experience of health and care services and value for money

- embrace the government’s “test and learn” approach to enable continuous improvement in real-time and build on existing good practice such as the NHS IMPACT Improving Patient Care Together framework

Summary of requirements for 2025/26

16. Building on the foundations laid by the Fuller Stocktake, approaches to tackle health inequalities, such as Core20PLUS5 and Core20PLUS5 for children and young people, outreach work and using data and local insights, systems should work with partner organisations to:

- apply a consistent, system-wide population health management approach which draws on quantitative data and qualitative insights to understand needs and risks for different population cohorts

- use this information to design and deliver the most appropriate care for each population cohort and to inform best-value commissioning decisions that empower frontline staff to provide more person-centred care, enabling people to live independently for longer

- continue to embed, standardise and scale the 6 initial core components of a neighbourhood health service (detailed in appendix 1) and ensure capacity and structures across providers are aligned to best meet demand

17. Best practice also suggests systems should consider:

- improving coordination, personalisation and continuity of care for people with complex needs, including increased agency in managing their own care, supported by:

- a single electronic health and care record that is actively used in real-time by frontline health and social care staff

- a care coordination function between the person or their carer and the wider multi-professional team supporting them if needed, working across organisational boundaries

- applying learnings from existing or emerging neighbourhood health models, such as enhanced health in care homes, the 24/7 neighbourhood mental health centres, women’s health hubs, family hubs and the Health and Growth Accelerators, ensuring that services are delivered at an efficient and effective scale

18. Systems should also tackle health inequalities when developing their neighbourhood health service. This will include:

- getting the basics right (such as ensuring services are accessible to people with disabilities and implementing reasonable adjustments as needed)

- engaging with local communities and working with them as equals to design and deliver services, working particularly closely with specific communities that have been historically underserved

- analysing outcomes by population demographics, deprivation, age, ethnicity, disability (supported by the reasonable adjustment digital flag) and inclusion health groups

Next steps

19. ICBs and local authorities are asked to jointly plan a neighbourhood health and care model for their local populations that consistently delivers and connects the initial core components at scale, with an initial focus on people with the most complex health and care needs. More mature systems will be working to develop an integrated neighbourhood delivery plan across the 6 initial core components, published as part of Joint Forward Plans and informed by engagement with local communities, that includes:

- improving collaboration and enabling effective ways of working

- agreeing commissioning models, new funding flows and contractual mechanisms between the NHS and local authorities

- workforce planning and development

- evaluation

- exploring the use of neighbourhood buildings across all partners, including local government, following on from recent ICB-led estates strategy work

20. We will provide further details of a national implementation programme over the coming months, designed for all parts of the health and social care system involved in delivering neighbourhood health. The initial phase of this programme will aim to work with at least one place in every system. These places will already be demonstrating a more developed approach to delivery at local level, with clear leadership across the ICB, local NHS and local authority. System partners in these places will be provided with facilitation support, as well as support to ensure robust evaluation and monitoring of progress. This test and learn approach will help to identify what is working most effectively and the conditions that are required to deliver a set of target outcomes. The national implementation programme will sit alongside a very small number of learning and evidence sites, which will test the model at scale, including its impact on flows in and out of an acute hospital.

21. We have shared case studies of existing good practice. NHS England regional teams, working with local government partners, will continue to have a key role in sharing and spreading emerging best practice and learning with systems.

22. We will continue to work with systems to co-develop the vision for neighbourhood health, focusing on removing barriers and creating the conditions for success. These guidelines will be kept under review as further learning emerges.

Appendix 1

The foundations of a neighbourhood health service are already in place in many areas across the country. This appendix describes 6 core components (A to F) associated with an effective neighbourhood service, as identified from the current evidence.

Initial 6 core components

Local systems will need to consider each component within the context of the needs of their local population and the current configuration of services. They will also need to evaluate how effectively individual interventions link together to improve the way services are delivered for their local population and the outcomes people achieve.

Given local projections of future need and demand, systems will want to consider how to have the greatest impact on health and wellbeing outcomes for the local population as well as benefits for the system when prioritising resource allocation, strategic leadership and quality improvement efforts.

A. Population health management

- Ensure there is a person-level, longitudinal, linked dataset encompassing:

- general practice and wider primary care

- community health services

- mental health

- acute care

- social care

- public health

Over time, this dataset should be broadened to include other data held by local or central government, including employment, education, safeguarding and housing status. It should be supported by appropriate data sharing and processing agreements. This should enable analysis of population health outcomes, biopsychosocial risk drivers and health and care system resource use. NHS England will continue to work with the National Data Guardian to support integrated care boards (ICBs) to navigate the necessary information governance requirements, but partners should already share existing data wherever possible.

- Apply a single, consistent system-wide population health management method to ICB analytics platforms to segment and risk stratify populations, based on complexity and forecasted resource use. Where systems do not already have an existing tool, they must work with the NHS Federated Data Platform team to select one which is compatible. In 2025/26, NHS England will work with ICBs to review the impact and evidence behind effective risk stratification to enable further signposting to validated tools.

- A population health management approach should be supported by a system-wide intelligence function used to:

- inform strategic commissioning and resource allocation

- enable providers to work together to best organise their workforce to deliver health and care

Systems should ensure they complement these analytical approaches with wider quantitative and qualitative insight into groups that might be under-represented in NHS datasets, for example, people with severe mental illness or learning disability or autistic people. Implementation of the Reasonable Adjustment digital flag information standard will also help analyse data for some of these population groups.

- Clinical data systems should have complementary functionality, including compatibility and integration between GP systems, digital social care records and other provider systems. This will support effective case finding, care navigation and risk-based prioritisation of proactive, planned, responsive and urgent care. This will also inform the design and work of neighbourhood multidisciplinary teams.

- Further guidance on using data to segment and risk stratify populations will follow in 2025, to complement existing resources and the Population Health Academy.

- Learn more in case study 1: Linking data and embedding a single system-wide population health management approach.

- Read case study 4: Transforming care through modern general practice and population segmentation to learn more about how automated stratification is integral to Brookside Group Practice’s approach.

B. Modern general practice

- ICBs are asked to continue to support general practices with the delivery of the modern general practice model, to deliver improvements in access, continuity and overall experience for people and their carers. This is a response to increasing demand and a foundational step to enable practices to move from a model of reactive to more proactive care.

- ICBs are expected to streamline the end-to-end access journey for people, carers and staff, making it quicker and easier to connect with the right healthcare professional, team or service, including community pharmacy, use of Pharmacy First and digital self-service options such as repeat prescription ordering via the NHS app. This approach will accommodate the needs of different groups and patients and support continuity of care.

- People and their carers should have the ability to access services equitably in different ways (online, telephone and in person) with highly usable and accessible online systems (the NHS app, practice websites, online consultation tools) and telephone systems. There should also be structured information gathering at the point of contact (regardless of contact channel) and clear navigation and triage based on risk and complexity of needs.

- Staff should have access to structured information about the complexity of the presenting complaint and need. This information should be organised alongside population segmentation (including by age) and risk stratification information into a single workflow. This approach will support staff in efficiently navigating and triaging needs safely and fairly, including enabling risk-based prioritisation of continuity of care and optimising use of the general practice and wider multi-professional team.

- Read case study 3: Improving access and workforce wellbeing through a modern general practice model for more information about Lime Tree Surgery’s approach, including using an online consultation platform and making use of Additional Roles Reimbursement Scheme (ARRS) staff.

- Read case study 4: Transforming care through modern general practice and population segmentation to learn more about how Brookside Group Practice have used digital innovation to improve primary care and health outcomes.

C. Standardising community health services

- Many community health services will play a key role in delivering neighbourhood health and care, and many of these services should be commissioned as part of an integrated neighbourhood health offer.

- When designing, commissioning and delivering neighbourhood health, ICBs and providers should be using the Standardising community health services publication (covering NHS-funded specialist support for people with physical health needs and neurodevelopmental services for children and young people). This will ensure funding is used to best meet local needs and priorities.

- Some people will have both physical and mental health needs, or drug and alcohol dependency. It is essential that care is planned to meet all health and social care needs and that service boundaries do not prevent seamless, joined-up care. Systems should continue to make use of the mental health Additional Roles Reimbursement Scheme, which is jointly funded with primary care, to improve primary care mental health and access to community-based mental health services for people of all ages, as well as through services such as NHS Talking Therapies for anxiety and depression. For children and young people, it’s also critical to join up with mental health services and mental health support teams in schools and further education. For people with co-occurring drug and alcohol dependency, services should engage with local authority commissioned substance misuse services. It will also be important to link in with VCFSE sector support for adults, children and young people around mental health, social isolation and substance misuse.

- Read more in case study 2: Addressing health inequalities faced by people with severe mental illness through mental health practitioners in primary care teams.

- Read case study 5: Standardising community health services to address variation and improve outcomes to learn more about how North Central London ICS developed a core offer as part of a 5-year plan.

D. Neighbourhood multidisciplinary teams (MDTs)

- The approach to establishing integrated neighbourhood teams has been well defined in the Fuller Stocktake. Such teams bring a wider range of expertise together, from across health, social care, VCFSE and wider partners to benefit a shared population. As part of this approach, there will need to be multidisciplinary coordination of care for population cohorts with complex health and care or social needs who require support from multiple services and organisations. They are expected to deliver proactive, planned and responsive care, and prioritise care based on individual people’s needs and the opportunity for greatest impact. Footprints should be designed to optimise neighbourhood working and partnership with local authorities. Detailed guidance on neighbourhood MDTs for children and young people has been published.

- Functions include overseeing or delivering holistic joint assessments, case reviews and deployment of coordinated provision, medication reviews, care planning for long-term conditions and personalised care and support planning, including social prescribing, comprehensive geriatric assessments and advanced care plans. For people with co-occurring severe mental illness, we would expect these functions to remain within core community mental health services. However, we would expect a joined-up approach to planning care for people with significant mental and physical health needs across teams.

- In best practice models, a core team is assigned for complex case management, with links to an extended team that enables access to additional specialist resource as needed. The composition of teams may vary depending on the population being served by the MDT and local prioritisation of clinical need. Teams could include GPs, specialist nurses or consultants (such as, specialist dementia nurses and secondary care clinicians, including paediatricians and geriatricians), district nurses, GP nurses, acute hospital consultants, allied health professionals, health visitors, mental health professionals, social prescribing link workers and social workers, home care staff, residential care home and nursing home staff, as well as wider system and community partners (such as from public health and the VCFSE sector).

- It is best practice to assign a care coordinator to every person or their carer in the population cohort as a clear point of contact to improve both their experience and continuity of care. The role could be undertaken by any member of the core team and will link into clinical triage and onward referrals as required. It will also set expectations with the person or their carer as part of the care plan process, so that all parties understand their part in improving outcomes.

- Case study 6: Strong working relationships as the bedrock of neighbourhood multidisciplinary teams (children and young people focused) highlights relevant learning from Connecting Care for Children.

- Learn more about Northamptonshire’s co-produced model of care in case study 7: Working with communities to mobilise change through neighbourhood multidisciplinary teams (frailty focused).

- Read more in case study 8: Provision of person-centred holistic care delivered by neighbourhood multidisciplinary teams (high intensity use focused).

- Case study 9: Women’s health hubs providing integrated care at neighbourhood level highlights learning about harnessing the skills of multidisciplinary teams.

- Case study 10: Strong relationships between system partners and multi-professional teams (palliative care and end-of-life care focused) looks at an example of collaboration across primary care, community care and the voluntary sector.

E. Integrated intermediate care with a ‘Home First’ approach

- Systems are asked to deliver short-term rehabilitation, reablement and recovery services (integrated intermediate care) taking a therapy-led approach (rehab or reablement care overseen by a registered therapist) working in integrated ways across health and social care and other sectors.

- Ensure referrals can be made directly from the community (step-up) or as part of hospital discharge planning (step-down), applying a ‘Home First’ approach, with assessments and interventions delivered at home where possible and working closely with urgent neighbourhood services.

- Implement good operational case management systems and measure outcomes (with reference to the objectives and metrics set out in the Better Care Fund policy framework for 2025 to 2026) to ensure best use of resources.

- Read more about how this can work in practice in case study 11: Supporting effective collaboration for ‘Home First’ rehabilitation, reablement and recovery services through a system-wide reporting suite and common analytics dashboard.

F. Urgent neighbourhood services

- Standardise and scale urgent neighbourhood services for people with an escalating or acute health need. This means ensuring urgent community response and hospital at home (virtual ward) services are aligned to local demand and work together (with access increasingly through a single point of access) to deliver a co-ordinated service. These urgent neighbourhood services should align with services at the front door of the hospital, such as urgent treatment centres and same day emergency care, which are also increasingly accessed through a single point of access.

- As part of ambulance service improvement of See and Treat and Hear and Treat pathways, senior clinical decision makers in a single point of access should provide advice and referral to appropriate services either before ambulance dispatch or as part of a “call before convey” approach. Single points of access should also provide clinical advice to other healthcare professionals and care home workers, so staff avoid calling 999.

- As outlined in the integrated intermediate care section above, ensure step-up pathways (to prevent avoidable admissions) and step-down pathways (to support timely and effective discharge) use resources efficiently and effectively. Service footprints should be determined locally, balancing scale of delivery with building on local relationships to ensure smooth referral pathways into urgent and planned care services. Where footprints span multiple neighbourhoods, services should still operate in a way that feels like a seamless service for people and carers.

- Read more in case study 12: Clear lines of accountability and clinical governance structures to deliver effective urgent neighbourhood services.

Secondary care contribution to neighbourhood health

Local acute services can provide significant contribution to the development of a neighbourhood health service. Home First and person-centred approaches need to be embedded throughout the health and care system so that appropriate risk-based decisions are always made, and hospital care only used when clinically necessary. In this way, every part of the system works collaboratively to reduce the risks associated with a hospital admission and a lengthy hospital stay if admission is unavoidable.

Clinicians in hospitals can continue to work collaboratively with community-based teams to ensure that their patients benefit from a neighbourhood health service by:

- supporting continuity of care in the community for people under the care of a specialist hospital team such as respiratory, diabetes, stroke or cardiology. This might include providing specialist input to neighbourhood MDTs such as through clinics delivered jointly in primary or community settings, using digital technology and infrastructure, or by establishing pathways into the hospital which avoid the emergency department, for example, by using urgent treatment centres, same day emergency care pathways or outpatient clinics.

- supporting the development of hospital at home (virtual ward), single point of access and community diagnostic centres*, including providing clinical advice and oversight as required.

- ensuring that frailty services are joined up in all settings, whilst maximising the delivery of these services within community settings. This will include the development of frailty-attuned hospital services, ensuring they connect with community frailty provision to support integrated end-to-end frailty pathways, and support for care transfer hubs, which arrange support services to assist discharge from hospital for those with the most complex needs.

By delivering proactive, planned, responsive and urgent care close to or in people’s own homes, effective local neighbourhood services will relieve pressure on acute services.

* Community diagnostic centres are likely to be considered anchor sites between primary, community and secondary care, enabling direct referral for diagnostic tests from a range of providers and optimising onward referrals to a range of health care settings for adults and children. 170 community diagnostic centres will be open by March 2025, with more than one in each ICB. The development of neighbourhood health services should include close working with associated community diagnostics centres to ensure that pathways are streamlined.

Planning for a flexible workforce

A flexible workforce working within and for local communities will be crucial for delivering neighbourhood health services.

To prepare for the move towards neighbourhood health, ICBs and local authorities are encouraged to connect as broadly as possible across their local communities to agree how best to use their collective local resources.

- Building on partnerships developed through the Better Care Fund, continue to develop joint demand and capacity assessment, modelling and planning across health and social care. This will provide a clear understanding of the capacity available to serve the local population across all providers and commissioners. This should include joint bottom-up mapping of existing workforce capacity, skills and capabilities across all partners and providers (including hospitals and mental health services) to optimise staff deployed across pathways, irrespective of organisational boundaries. This co-ordinated approach will help staff be deployed more flexibly where needed most, enable continuity of care, and create opportunities for streamlined joint recruitment, training and staff rotation across services.

- Take a user-centred approach to the design of teams, including job planning across different settings. This may include upskilling teams within the MDTs to cover multiple functions that traditionally may have been delivered separately so they are safely able to work in a more agile way and increase continuity for people and carers.

- Ensure staff are aware of, and are involved in building, the local neighbourhood service model to optimise the use of all services, including wider primary care, general practice, mental health, community health services, neighbourhood MDTs, social care services and “self-access” options where appropriate, supported by shared digital tools.

- Identify barriers and opportunities to better enable productive integrated working so that staff have the skills and tools to safely work across organisational boundaries and serve their local populations, ensuring best use of funding to meet local need, and improving workforce interactions and experience. This should include ensuring care workers can deliver delegated healthcare activities such as blood pressure checks and other healthcare interventions. The government has recently published new guidance on safe delegation to care staff.

Case studies

These case studies provide examples of existing good practice that forms the foundations of neighbourhood health.

Publication reference: PRN01756