Idea #1 Mapping the family and support network

What’s the idea?

There may be a range of people in the mother’s family and wider support network who are important to her mental health and may be able to contribute to her recovery, as well as needing support themselves.

Mapping the family is an opportunity to consider relevant family members’ interpersonal experiences, including any experiences of perinatal loss.

Why implement it?

Mapping can:

- identify the people who the mother relies on for support

- give clinical indications about the focus of the intervention, such as family therapy or couple work that directly involves others

- form the basis for providing joined-up care between services (see Idea #10: Partnership working and transitions)

- provide information about interpersonal traumas such as loss or abuse which may impact on mental health and recovery.

Actions to consider

- Explore who is in the mother’s family and support network, at the earliest opportunity.

- Regularly ask questions about the family system throughout the mother’s involvement with the service, as key relationships and wishes may change.

- Hold in mind that mothers may not want others involved or may feel conflicted about their involvement, particularly if coercive control features in their relationships.

Perinatal loss

Some mothers, partners or other family members may have experienced pregnancy loss or the death of a baby before or during the current episode of care. Regardless of gestation, age, or reason, such losses can exacerbate pre-existing mental health disorders or precipitate new mental health difficulties.

Any parent who has experienced perinatal loss is at increased risk of depression, anxiety disorders, including tokophobia (extreme fear of childbirth) and birth-related trauma. Although grief itself should not be pathologised, it is important to ensure that mental health needs and symptoms are not mistakenly attributed to grief

Practice tips: box 1

Asking about the family and support network: Genograms

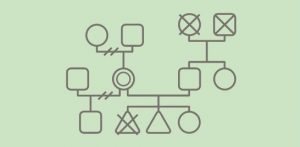

A genogram can be a useful tool to start conversations and map the family system [ref. 11 and 12]. Genograms can also be used to explore the strength or quality of different relationships, patterns of responding and coping that may be contributing to the current difficulties, and experiences of loss, including previous perinatal losses.

Although it can be helpful to follow standardised formats when producing the genogram, do not feel constrained about drawing a genogram ‘correctly’. Do not let IT systems limit what you ask or what you record. For example, you may draw a genogram by hand and save the scanned image.

Example of a genogram

Practice tips: box 2

Asking about the family and support network: Open questions and systemic approaches

Ask open questions to discover who is in the family system and who is important to the mother, without making assumptions. Stay curious.

Who is in the family system, and how does she experience these relationships?

- Who does she consent for information to be shared with?

- Who may she want to be invited into assessment or treatment sessions, or to be involved in aspects of her care?

- Who would she want to be told about her involvement in the service and who would she not want to be told?

- Who is she close to? Is there anyone she has a more difficult relationship with?

- Who does she turn to for support? Who does she feel is not supportive?

What are the culture, beliefs and values within the family system? These will affect the approaches needed to foster engagement.

- How is the role of men/fathers viewed? Are fathers expected to be involved in childcare or would this be unusual? Be sensitive to different cultural, ethnic and religious influences.

- How are mental health disorders and services viewed? Is she worried about the views of other family members and does she plan to keep her involvement with the service hidden from them?

- Who has similar/different values and beliefs to the mother?

Which other services or groups may be important?

- Has she received support from other health or mental health care providers, third sector organisations, religious or community groups? What did she find helpful?

- Does she have other networks that are important to her (for example work or social networks)?

Practice example: Staying curious about the family

Coombe Wood Mother and Baby Unit (MBU), Central and North West London NHS Foundation Trust

Coombe Wood MBU is committed to a “think family” approach. Recognising that supporting families can help mothers to recover quicker, the unit aims to support partners and other family members in order to enable the mother’s recovery whilst also helping families achieve their best level of functioning.

They feel it is important that families hear this message from the first contact with their service. Mothers are told that “we work with you and your family” when they arrive at the MBU, and staff see the family within 72 hours of the mother’s admission.

They use a genogram approach to explore the mother’s support network, using questions such as: “Who is in your family?” “Is there anyone who supports you?” “Are there any difficulties in your family or friendships at the moment?” These can be followed by questions such as “Would you like them to be here?” Staff find this approach helps make sense of what has happened prior to admission.

The information generated enables them to develop clinical formulations and treatment plans that take these factors into account, potentially locating the ‘problem’ outside the mother in the wider system. This then determines the type of support and treatment offered to the mother and her family, such as family therapy, couple-focused work, or one-to-one support for mothers.

If supportive others are not identified by the mother, staff note who does and doesn’t visit and use these observations to start conversations about support networks.

When a mother does not want others involved in her care, staff explore this and whether ruptures in relationships may be contributing to her current difficulties, to identify where it may be helpful for repairs to be made. If partners and other family members are not directly involved in the mother’s care, staff ensure that they are held in mind throughout.

Asking about domestic violence and abuse (DVA)

While working with families it is important to be aware that:

- One in four mothers in contact with mental health services may be experiencing violence, abuse and coercive control.

- DVA often starts or intensifies in the perinatal period.

What is DVA?

In the UK it is defined as: ‘Any incident or pattern of incidents of controlling, coercive, threatening behaviour, violence or abuse between those aged 16 or over who are, or have been, intimate partners or family members regardless of gender or sexuality. The abuse can encompass, but is not limited to: psychological, physical, sexual, financial, and emotional’ [ref. 13].

All staff working in perinatal mental health services should know how to enquire about, identify, and respond to DVA. Services need to link in with their local safeguarding processes, information-sharing processes and multi-disciplinary teams (MDTs).

The Department for Work and Pensions launched a national Reducing Parental Conflict Programme to support implementation of evidence-based interventions. Local authorities have since been working to increase provision to tackle parental conflict.

Practice tips: box 3

Identifying and responding to Domestic Violence and Abuse

Informed by the King’s College London (2019) Linking Abuse and Recovery through Advocacy for Victims and Perpetrators (LARA-VP) guidelines.

How should I ask mothers about DVA?

- Ask at assessment and follow-up appointments as people may not disclose the first time they are asked.

- Ensure you are somewhere private and that you have explained the limits of confidentiality.

- Ask about psychological, sexual and financial abuse as well as physical abuse.

What if a partner or other family member discloses being a perpetrator?

- Be clear that violence and abuse is unacceptable. Assess any immediate risks.

- Consider signposting to Respect – a charity offering information and advice to people who are abusive towards their partners or family members.

What should I do next?

Discuss any disclosures with your line manager or MDT.

- Make sure you know who is your trust’s:

-

- adult safeguarding lead

- child safeguarding lead

- Multi Agency Risk Assessment Conference (MARAC) representative

- local DVA.

-

- Follow local safeguarding procedures for any immediate risks of harm.

- Keep the mother informed about what is happening.

What about false allegations?

Many DVA incidents go unreported, and false accusations of DVA are rare. This applies to all types of DVA. Therefore, you should take any disclosure of abuse seriously; being disbelieved can be distressing and damaging.

Confidentiality and consent to inform and involve others

Once the family structure has been explored and mapped with the mother, it is important to seek consent from the mother about who can be involved and informed about her care, and how much information can be shared (full, partial or no information).

These decisions also need to be clearly documented in the mother’s notes.

Actions to consider

Services should:

- assess the mother’s capacity to consent to sharing information. If she does not have capacity, then follow local safeguarding and Mental Capacity Act policies. A clinical decision will need to be made about whether it is in the mother’s and baby’s best interests to involve others

- fulfil the duty to share specific information relating to the baby’s care and wellbeing with the other parent, if there is shared parental responsibility for the baby. This may be particularly important if the mother’s mental health disorder is affecting her ability to provide care for the baby

- once consent has been provided to make contact and/or share information, ensure this is done.

Services could:

- consider whether generic information can be shared without breaching confidentiality, if consent is not given to share specific details. For example, if a mother does not want information about her health or care to be shared with her partner or family member, can general information be provided on mental health disorders?

- check whether there is an advance decision in place about who should be involved and how, if the mother’s current capacity or decision-making is impaired

- encourage the mother to make an advance decision about involving others if she is currently well enough, which may be helpful if her symptoms deteriorate or she becomes unwell again in the future

- be aware that if a mother is experiencing delusions these may involve her partner or other family members. This may result in her refusing contact or consent from them to be involved in her care. Although this can be very upsetting and destabilising for the family, the mother’s wishes should be adhered to, subject to any advance decisions. Safeguarding policies must be complied with at all times. It may take some time to establish whether the mother’s concerns about a family member are due to a delusion or a reality. The partner or family member may feel excluded and under suspicion. Take care to sensitively gain objective perspectives, where possible

- hold the whole family in mind when developing care plans, even if the mother has not consented for the family to be directly involved. The care plan may have implications for the family, such as planning leave or discharge back home. Discuss with the mother whether and how to involve the family for these aspects of the care plan

- check consent decisions periodically, because consent is a dynamic process and feelings about others may change over the course of the mother’s contact with services.

Parental responsibility (PR)

Always prioritise safeguarding. Escalate concerns and consult with relevant legal departments within the trust.

- Some partners may not have PR. For example, where the baby’s birth has not yet been registered and the couple are not married or in a civil partnership, the father does not have PR. Stepparents may be at home with older children, without PR for those children.

- In some families both parents have PR but disagree about the child’s best interests. For example, parents may be separating and a father with PR may refuse permission for the child to be admitted to a MBU.

- Sometimes it is necessary to override the wishes of parents with PR even if they agree with each other. For example, a partner who is on the sex offenders register may not be allowed to visit a mother and baby in an MBU, despite the wishes of both parents.