1. Key messages for those responsible for the commissioning of mental health inpatient services

1.1 As well as improving experience and outcomes, this will support people to strengthen their relationships, sense of belonging and connection to local services.

1.2 Creating this strategic plan and achieving its aims will require strong collaboration, particularly with local authorities and public health, and the harnessing of local information such as that within the Joint Strategic Needs Assessment. This framework summarises the issues the plan will need to address as a minimum.

1.3 The strategic plan also needs to identify how data will be collected, reported, and used to monitor progress across NHS and independent sector providers. This will include how services will be commissioned with models of care that mitigate the risks identified in this guidance, including those associated with placing people at distance.

1.4 Local strategies need to cover within them how they will cease the practice of sending people to inpatient services at distance from their home and/or to outdated or risky models of provision. This includes acute and rehabilitation inpatient services.

1.5 Localising care will require a phased implementation approach, which may include shortening stays, preventing inappropriate readmissions to inpatient services and redirecting resources from poor quality, and outdated inpatient provision towards the community.

1.6 Achieving the vision of ‘what good looks like’ will require new relationships, the shifting of resources and power and reshaping of the provider market. Provision across the NHS and Independent Sector needs to be balanced, achieving the right outcomes for local people and represent good quality. This includes making appropriate use of the skills and expertise within Voluntary, Community, Faith and Social Enterprise organisations.

1.7 Commissioners of mental health inpatient services will need to forge strong networks within and across systems, recognising their interdependency with a range of services across the community including social care, education and health and justice agencies.

1.8 Building community services, including housing and support, will be crucial in enabling people to return to the place they call home. Thorough planning with people, particularly those who have been in hospital and/or out of area for a long time, will be important to determine where, how and with whom they would like to live.

1.9 New models of care and support should be co-designed with people with recent lived experience of inpatient provision, families, and advocates, those who work within them, as well as the wider community. This will include working together to reduce the risks associated with transitions across multiple interfaces experienced by people and families.

1.10 The speed of change locally will depend on the availability of a skilled and competent workforce, including specialist professionals who can work across the system. Ensuring the capability, capacity as well as the wellbeing and safety of the inpatient workforce is paramount. This includes recognising and mitigating the risk of compassion fatigue, and continued action to address longstanding problems such as staff shortages.

1.11 To deliver a local workforce who can localise provision will require a system-wide approach to workforce planning; one that includes all NHS commissioned services including those within the independent and voluntary sectors.

1.12 Future commissioning, design and delivery of mental health inpatient services should meet the requirement for inclusive, local, high quality, effective and compassionate care. Barriers to delivering the right care and support at the right time need to be removed.

1.13 Integrated care systems and providers of inpatient mental health services are required to use data and intelligence to inform improvement and decision making, setting clear standards of what high quality care and outcomes look like (NHS England, 2021). This includes identifying and monitoring groups within their local population who have poorer access, experience, and outcomes from care.

1.14 Commissioners are required to evaluate the outcomes, effectiveness, and safety of current inpatient provision (both local and out of area services) with a particular focus on the experience of people and families.

“If we are going to truly change things for the better, we need to think about people as a whole – what makes their lives, and their needs, wants and ambitions… these varied and personal needs must be reflected in the support and treatment we receive from public services too. Here we should be striving for needs-based not diagnosis-based care and treatment… we also need to empower and enable clinicians to work with us to understand our needs as a whole before agreeing a course of actions to keep us well. We need choice and to practice shared decision-making.” Person with lived experience.

2. Introduction

2.1 Mental health inpatient services form a vital part of a landscape of care, treatment and support for individuals who are experiencing mental ill health. This includes primary care, social care, and specialist healthcare teams.

2.2 Many mental health inpatient services across the country are delivering good care and outcomes. They show what is possible and achievable.

2.3 However, while significant progress has been made, some parts of the country still over rely on certain types of bed-based provision (including out of area placements) and the use of poor quality and outdated services (RCPsych, 2022; GIRFT, 2022).

2.4 Recent high-profile quality failings in both NHS and independent sector hospitals have rightly sharpened the focus of providers, commissioners, and regulators on mental health inpatient provision (The Independent, 2022; Department of Health and Social Care, 2023; Samuel M, 2022).

2.5 In 2022/23 the NHS England mental health, learning disability and autism quality transformation team undertook an extensive engagement exercise with key stakeholders. The aim of this exercise was to gather the views and expertise of individuals concerned with the commissioning, delivery, and improvement of mental health inpatient services. This included clinicians and people with lived experience of inpatient services and their families. In doing so, identifying key themes and priorities where intervention and support to improve quality could be employed to best effect.

2.6 This ‘ask’ included a clear request for a shared understanding of ‘what good looks like’ for mental health inpatient services and a call to action. To support commissioners and providers to build on existing good practice to ensure that every person who is admitted to an inpatient service, experiences safe, personalised, effective, and compassionate care.

2.7 This guidance forms part of that support, which is comprised of several workstreams, including work focussed on improving the culture of inpatient services and existing commitments such as those contained within the NHS Patient Safety Strategy. It is aimed at improving the quality and safety of care that people experience in mental health, learning disability and autism inpatient settings.

2.8 This guidance is about how integrated care boards can use the funds they are currently investing in inpatient care to provide better services which are tailored to patient need, not about additional funding. If we collectively shift our investment from services which do not help people get better to more proactive support for all, we should be able to achieve better results within our existing funding.

Aims of the framework

The overarching framework summarises the commissioning guidance relating to mental health inpatient provision. It aims to:

- Provide guidance for those responsible for the commissioning of mental health inpatient services and within this, advance the system-wide requirement to ensure that services are local, inclusive and deliver safe, personalised, and therapeutic care.

- Support systems to develop local plans for change, so that inpatient provision better fits the needs of the population, makes more effective use of the funds available, and protects and improves the lives of citizens in the locality.

2.9 The detailed guidance is comprised of:

a) Acute inpatient mental health services for adults and older adults

b) National guidance to support integrated care boards to commission acute mental health inpatient services for adults with a learning disability and autistic adults

c) Commissioner guidance for adult mental health rehabilitation inpatient services

2.10 The detailed guidance documents were developed with frontline clinicians and people with lived experience of inpatient services, either directly or as a carer. This included visits to inpatient provision, workshops, reference and task and finish groups. In addition, the design and content of this overarching framework has been informed by a commissioner advisory group whose membership represents regional, system and provider collaborative commissioners (see Appendix 4).

Audience

2.11. This framework has been developed for use by those who have commissioning responsibility for the mental health needs of their local population. For this guidance, it is recognised that commissioning is a function and can be carried out by different individuals and organisations, separately and collaboratively, depending on local arrangements. For ease, within this document, those with commissioning responsibility will be referred to as “the commissioner”.

2.12. The commissioner of mental health inpatient services may vary nationally, and could be:

- An integrated care board (ICB)

- A provider collaborative

- An NHS-led provider collaborative

2.13. The framework also has relevance for mental health providers, professionals, and partnership organisations across Integrated Care Systems and may include:

- Local Authority Commissioners

- Commissioners of Specialised Mental Health, Learning Disability and Autism Services and Health and Justice Services

- Providers of community and hospital healthcare provision both NHS and independent sector

- Voluntary, Community, Faith and Social Enterprises (VCFSE)

- People with lived experience and organisations that advocate for and represent them.

Scope

2.14. The scope of this framework (Table 1) was determined by the views of stakeholders and shaped by work underway or planned, e.g., within clinical reference groups, and by reviewing the evidence for serious quality failings in those types of services that have recently and frequently featured in such reports.

Table 1: Scope of the commissioning framework

| Scope | Adults |

|---|---|

| Included | Acute mental health inpatient services including services for people with a learning disability or who are autistic, and psychiatric intensive care units. Mental health rehabilitation inpatient services including services for autistic people and people with a learning disability – open and ‘locked’. |

| Excluded | All adult secure Adult eating disorder services Mother and baby units Adult D/deaf Obsessive-compulsive disorder, body dysmorphic disorder services |

2.15 While the primary focus of this framework is inpatient provision, improved models and pathways will depend to a large degree on the capacity and capability within the local community, its assets and strengths. Alongside this is the need for relevant expertise to lead the design.

2.16 It is therefore essential that local system partners forge strong relationships and collaborate to establish joined up, effective pathways and transitions, and share knowledge, skills and support.

2.17 Central to this is addressing the way we directly care for people, and specifically what is often called the ‘therapeutic relationship’ (O’Brien L, 2001). One definition of this is a “partnership that promotes safe engagement and constructive, respectful, and non-judgemental intervention” (McCormack B, McCance T, 2016). The primary importance of the therapeutic relationship, and the culture of care more broadly, will be covered through the Culture of care standards for mental health inpatient services.

3. Case for change

Too many people are detained on wards that are far below the standards anyone would want for themselves or their loved ones. Sir Simon Wessely: Independent Review of the Mental Health Act 2018.

3.1 The views of stakeholders, including clinicians, providers, commissioners, regulators and, specifically, people with lived experience, confirm the case for change.

3.2 Reports continue to detail quality failings within mental health inpatient services, including those specifically for people with learning disabilities and autistic people (House of Commons Health and Social Care Committee, 2021).

3.3 Detentions under the Mental Health Act have been rising alongside increasing concerns about the use of long-term segregation, seclusion, restraint, and other coercive measures.

3.4 Many people who have experienced poor or abusive mental health inpatient care share characteristics that make them more susceptible to discrimination and inequality NHS Race and Health Observatory, 2022). This includes people given a particular diagnosis such as ‘personality disorder’ (Klein P, Fairweather AK, Lawn S, 2022) and/or who are labelled as ‘challenging’ and/or ‘complex’ (Cambridge P, Beadle-Brown J, Milne A, Mansell J, Whelton B, 2007). They may find themselves denied access to mental health services and even be at risk of criminalisation.

3.5 Recent inquiries and rapid reviews (NHS England, 2023) into mental health inpatient services, including those specifically for people with a learning disability and autistic people, have identified particular ‘setting conditions’ and/or characteristics of service models that are associated with serious quality failings (see paragraph 3.12 below). These factors can undermine the delivery of high quality, person-centred care and also increase the risk of a ‘closed culture’ developing.

3.6 The CQC describes a closed culture as “a poor culture in a health or care service that increases the risk of harm. This includes abuse and human rights breaches. The development of closed cultures can be deliberate or unintentional – either way it can cause unacceptable harm to a person and their loved ones.” (Care Quality Commission, 2022).

3.7 Understanding this picture is imperative as the design of some inpatient service models mean that people are more likely to be at risk of deliberate or unintentional harm. Even when care is deemed acceptable, it may be a service model that represents poor value for money, limited or non-existent outcomes as seen within inpatient mental health rehabilitation services (Care Quality Commission, 2020).

“No-one had an overview. I was the only one keeping tabs on what was happening… it shouldn’t have been me doing it.” Family carer of someone placed out of area.

3.8 Sending people away from their home communities risks dislocating their care and increasing their length of stay and sense of isolation; however, this is something experienced by all too many people.

3.9 People who are admitted to an out of area hospital have, on average, longer lengths of stay (Crossley N, Sweeney B, 2022), poorer clinical outcomes (including increased risk of suicide (Royal College of Psychiatrists, 2022) and poorer experience of care (GIRFT, 2022).

3.10 The Getting It Right First Time (GIRFT) national report for mental health rehabilitation noted that half of the 3,500 people who use inpatient mental health rehabilitation beds in England receive care outside their local area, mainly from independent providers, away from their families and support network.

3.11 A 2021 NHS England report detailing the lessons learned from safe and wellbeing reviews, noted that 57% of people with a learning disability and autistic people were placed outside their originating ICS or transforming care partnership. Several factors are leading to this situation, not least a lack of locally available alternatives.

3.12 The design and location of specific service models can exacerbate this position, by their design and location. The types of hospital that often feature in reports detailing quality failings commonly:

- make use of ‘spot contracts’

- admit people from across the country

- are disconnected from local pathways

- are in single site, often isolated, locations

- admit into one service people with different diagnosis but who are often described as ‘challenging’ and/or ‘complex’.

3.13 Moreover, once someone is detained within an inpatient service, they may be subject to further coercive and restrictive practices including seclusion, segregation, and restraint, as identified in the CQC review Out of sight – who cares? (2020).

3.14 Involuntary admission to hospital can be a traumatic, frightening, and confusing experience for people. The case for reducing compulsion is inarguable and set out in detail in the Independent Review of the Mental Health Act and the proposed reforms in the Draft Mental Health Bill.

3.15 The number of people detained in hospital continues to rise year on year and there is disproportionate use across the population; in the year to March 2022, black people were almost five times as likely as white people to be detained under the Mental Health Act.[18]

3.16 People with learning disability and autistic people are disproportionately likely to experience restrictive interventions while in hospital, illustrated, for example, by the high number of autistic people in long-term segregation (Department of Health and Social Care, 2021).

3.17 Legislation requires mental health inpatient services to increase transparency, accountability and reduce the use of restrictive practice. The Mental Health Units (Use of Force) Act, commonly known as Seni’s Law, gained Royal Assent in 2018, but despite this progress in reducing restrictions has been patchy.

3.18 In 2020 the CQC published a report on the use of restraint, seclusion and segregation for autistic people, people with a learning disability and/or mental health condition, noting that of those subject to these restrictions: “Almost 71% had been segregated or secluded for three months or longer. A few people we met had been in hospital for more than 25 years, but how long they had been in segregation or seclusion had not been recorded beyond 13 years.” (CQC, 2020).

3.19 Without a concerted effort to localise and realign inpatient services in a way that harnesses the potential of people and communities, people may continue to find themselves:

- stranded in hospital when they are ready to leave, often for many months or years

- sent away to services at distance from home and the people who care about them

- subject to overly restrictive practice, including the use of long-term segregation

- susceptible to poor and abusive care

- stigmatised and discriminated against and at risk of criminalisation.

3.20 We know that the design of services has a major role in creating the setting conditions for people who experience, and those who work within, inpatient services to flourish.

3.21 It is vital that service models are intentionally and primarily designed around the needs of people who experience them and are not driven by market or other external forces.

3.22 Maintaining the status quo is not an option as some service models are hindering rather than helping the delivery of high quality, safe and compassionate care. It is imperative that the commissioned inpatient provision meets our legal, moral and ethical obligations, and systems can co-produce a bold and radical vision for the future; one that not only delivers inpatient services that are the best that they can be, but also helps people feel they belong and are recognised as full citizens with all the rights and responsibilities that denotes.

4. Commissioning to achieve ‘what good looks like’

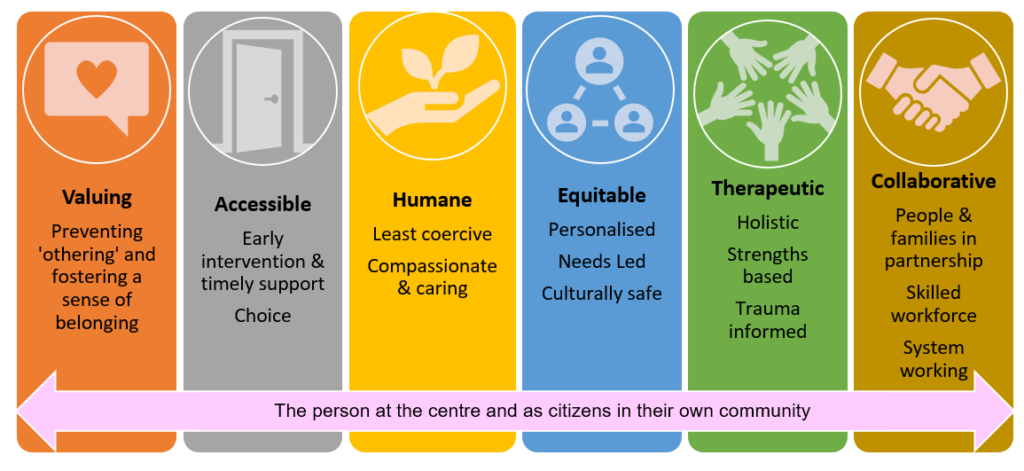

4.1 Each of the detailed mental health inpatient service documents provides the specific vision and key principles for that service, but there is common ground between them across the descriptors of ‘what good looks like’ as described in Figure 1 below:

Figure 1: What good looks like principles

The person at the centre and as citizens in their own community

- Valuing: preventing ‘othering’ and fostering a sense of belonging

- Accessible: early intervention and timely support. Choice

- Humane: least coercive. Compassionate and caring

- Equitable: personalised. Needs led. Culturally safe

- Therapeutic: Holistic. Strength based. Trauma informed

- Collaborative: People and families in partnership. Skilled workforce. System working

4.2 This emphasis on the descriptors of a good service rather than an overly prescriptive structure or ‘best practice’ model recognises that the configuration of services should be determined by local systems and co-produced with experts by experience. They provide a scaffold for the commissioning of inpatient mental health services, including those specifically for people with a learning disability and autistic people.

4.3 Complementary to this are the Culture of care standards for mental health inpatient services.

4.4 We know that across the country there are services already working to a similar vision, descriptors and commissioning principles, using the investments provided in the NHS Long Term Plan to bring about change. Therefore, the content of later focused sections on acute inpatient services, rehabilitation inpatient services may be familiar to people with experience within the sector.

I and We statements

4.5 Below we embellish these descriptors of ‘what good looks like’ with ‘I and we’ statements. ‘I’ statements describe what good looks like from an individual perspective and ‘we’ statements are indicators or signposts for commissioners on how they can work together with people, families, staff and other stakeholders to achieve the vision of ‘what good looks like’ in mental health inpatient care. Good mental health inpatient services are;

Valuing: Preventing ‘othering’ and fostering a sense of belonging

I statements

- I am valued as a person, and my individual needs and wishes are respected.

- I feel listened to and that my voice is heard.

- I have a sense of belonging and feel part of my own community.

We statements

- We will ensure that the people who experience inpatient services and the staff who work within them, feel valued and cared for, benefitting from a culture that lives its values.

- We will work to ensure we can hear the voice of people who may need to call on mental health services and their families; we employ a range of communication methods to reflect individual preferences and needs.

- We will commission and provide services that are part of a local pathway of care that promotes inclusion, strengthens individuals’ rights, and is orientated towards citizenship.

- We will work with people in ways that prevent othering, foster a sense of belonging, reduce stigma, and enable people to maintain their social ties.

- We respect people as citizens and valued members of their community. We are here for all our people when they need us, irrespective of where they live, their background, age, ethnicity, sex, gender, sexuality, disability, or health conditions.

Accessible: Early intervention and timely support

I statements

- I can access services based on my need and I do not feel excluded or stigmatised by my diagnosis.

We statements

- We provide services that are needs led and accessible to all who need them, and we are proactive in facilitating choice.

- We will ensure that admissions are appropriate, purposeful, therapeutic, and timely.

- We will employ interventions designed to avoid unnecessary admission to hospital, but when inpatient care is appropriate, it will neither be impeded nor regarded as the ‘last resort’.

Humane: Least coercive; compassionate and caring

I statements

- I am first and foremost treated as a human being.

- I am cared for in an environment that is considerate of my individual strengths and needs.

- I am supported by staff who talk with me, not to me, using a way of communication that is preferred by me.

- I am supported to plan and prepare for important changes such as transitions between services, or discharge home.

We statements

- We are unwavering in our commitment to commission inpatient services that are least restrictive and where people are not confined in conditions of greater security than required.

- We will plan discharge with each person from the very start of their admission, mitigating the risk of delays and ensuring that transitions between services are carefully considered.

- We are person-centred in our approach and staff are supported to respond to people’s distress with compassion.

- We will pay attention to our hospital environment and the impact it has on the wellbeing of people experiencing inpatient services and the staff working within them.

Equitable: Personalised, needs led, culturally safe

I statements

- I feel valued and respected for who I am.

- I can be myself around peers and staff.

- I am not discriminated against for who I am and the choices I make.

- I feel difference is understood, respected, and celebrated.

- I feel that my cultural needs and preferences are respected by all the staff who support me.

We statements

- We will commission and deliver services where everyone counts, is treated with dignity and is safe. Where a person’s identity is not contested, their individuality is recognised and who they are and what they need is respected.

- We will work with people (and those who know and love them) to identify ‘what matters to them’ and make sure that the care they receive is personalised, needs led and respects their human rights.

- We will work with people to make sure we share decision making, acknowledging that even when people are acutely unwell, they are experts in their own lives and have valuable contributions to make about the support they need.

- We will be relentless in our pursuit to identify and address inequalities that exist within our local pathway. We are committed to ensuring everyone is valued irrespective of where they live, their background, age, ethnicity, sex, gender, sexuality, disability, or health conditions.

- We will strive to achieve parity of esteem, valuing mental health equally to physical heath, enabling people living with a mental health condition to have an equal chance of a long and fulfilling life.

- We ensure our environments are inclusive and accessible for everyone. We are thoughtful about people’s cultural needs and people with disabilities. We pay close attention to people’s individual sensory needs, particularly for autistic people and trauma survivors.

Therapeutic: Holistic, strengths based, trauma informed

I statements

- I will be able to access a range of support that meets my need.

- I feel I have the time and space to form trusting relationships with the people involved in my care.

We statements

- We know that therapeutic relationships are the strongest predictor of good clinical outcomes, so we will support staff to prioritise building relationships with people and enable continuity of care.

- We recognise that many people who are admitted to inpatient services will have experienced trauma at some point in their lives. Therefore, we will place emphasis on creating physical and emotional environments that promote feelings of safety and therapeutic relationships that are based on trust, respect, and compassion.

- We will invest in inpatient services that demonstrate a holistic, strengths based, integrated approach to care and make sure that mental and physical health conditions are considered, managed, and monitored.

- We will undertake assessments, interventions, and treatments that are evidence-based and delivered in a timely way.

- We are committed to delivering services that demonstrate therapeutic benefit. This includes continuous improvement of the inpatient pathway, co-producing service developments, making best use of data and using quality improvement methodology.

- We will develop a workforce that is consistent with national workforce profiles and has the right skills and knowledge to ensure people have access to a full range of multidisciplinary interventions and treatments.

Collaborative: People and families in partnership, skilled workforce and system working

I statements

- I have a voice and I feel my views and choices are respected.

- I am able to access independent advocacy if I want to.

- I can make use of peer support as I wish.

We statements

- We respect the views and advanced choices of the people we serve and the contribution of people who know and care for them.

- We will invest in peer support and facilitate easy access to independent advocacy.

- We understand that safe and high quality inpatient mental health care relies on staff being able to ‘be with’ and work in partnership with people in a high state of distress. We will provide support for our staff to enable them to do this compassionately, safely, and respectfully.

- We are committed to providing the right resources for all our staff to ensure their time is protected to care, and that they can respond appropriately to the therapeutic aspects of their work.

- We will work in partnership across our system to ensure that locally, there is a range of services to support people within their local communities.

- We are committed to working together so that no-one is inappropriately admitted to hospital or experiences a delayed discharge.

Support people as citizens: The person at the centre and as citizens within their own communities

I statements

- I am supported to access the things that matter to me.

- I feel my hopes, dreams, and plans for the future, are heard.

- I have a sense of belonging with the community I identify with.

We statements

- We will actively work to promote the social inclusion of people with mental health need.

- We will ensure that mental health services, by their design and activities, support the active participation of people in their local community.

- We respect everyone’s rights and responsibilities as citizens, supporting them to make real their hopes and aspirations, to contribute and to lead fulfilling lives.

“Being able to make decisions about one’s life, including the right to choose one’s own healthcare – is key to a person’s autonomy and personhood.” (World Health Organisation (2022) ).

5. All means all

5.1 A core value enshrined in the NHS Constitution is that ‘everyone counts’, that nobody is excluded, discriminated against or left behind. There is also a national strategy to advance mental health equalities.

5.2 However, we know that many of the problems and issues identified in section 3 apply disproportionately to some groups, and that our fundamental duty to promote equality and respect human rights is not universally upheld.

5.3 Inpatient mental health services need to work for everyone and be committed to meeting the responsibilities under the Equality Act 2010, including the duty to make reasonable adjustments using tools such as the Reasonable Adjustment Flag and the The Reasonable Adjustment Digital Flag action checklist).

5.4 Adjustments should meet the needs of the individual, not of any characteristics or conditions used to describe the person. Any required adjustments should be identified through personalised care and support planning conversations around what matters to the person and what good support looks like to them. The person may already have a plan that can be reviewed and amended to include information about reasonable adjustments.

5.5 Inpatient services also need to demonstrate that they are anti-racist to counter systemic racism; that is, go beyond increasing access and ensuring culturally sensitive and competent provision.

5.6 Mental health inpatient services serve people who face discrimination in their daily lives, based on their race, class, gender or sexuality. These forms of discrimination often intersect, amplifying their detrimental effects; and people who face discrimination may also be alcohol or drug dependent, have other health needs and/or disabilities.

5.7 The use of particular diagnostic labels and descriptions attributed to some people and their relationship with services such as people who are labelled as having a ‘personality disorder’ or described as ‘high users’, can further exacerbate the discrimination they face (NHS England, 2023).

5.8 It is essential that locally agreed plans are in place to manage transitions between services, agencies and localities, safely and effectively. Transitions between services can present significant risks for people of all ages, as often several interfaces need to be crossed – between different providers as well as different health, social care, education and criminal justice agencies. Sometimes, ‘boundary disputes’ occur at these points of transition and/or where partnership working is weak, adding to the stress for the person and their families.

5.9 A guiding principle is that access to mental health services should be premised on the needs of the individual, and not determined by exclusion criteria. The use of mainstream mental health services must always be the ‘default’ position, including for people with a learning disability and autistic people.

5.10 Where people require reasonable adjustments or have additional needs that fall outside the remit of inpatient mental health services, expertise and support may be sought from specialists, e.g. learning disability, autism, and drug and alcohol services.

5.11 Mental health inpatient wards should have appropriate signage, soft furnishings and flooring, and be sensory friendly to meet the diverse needs of the people who access inpatient provision, including people who may be older, have physical and/or sensory impairments or sensitivities, have a learning disability or who are autistic people. Further guidance on meeting autistic adults needs can be found here: NHS England » Meeting the needs of autistic adults in mental health services.

5.12 Communication preferences should be understood and accommodated, including by providing access to interpreters and information in a range of formats, using augmentative and alternative communication, and meeting the requirements of the Accessible Information Standard.

5.13 Ward environments need to be in line with the guidance on same-sex accommodation, which includes ensuring trans individuals are cared for on the appropriate gendered ward.

5.14 Inpatient services need to make sure that people have access to and are supported to meet with independent advocates who are culturally appropriate and peer support workers, regardless of the legal status of their admission.

5.15 Staff within inpatient provision should be representative of the local community and be sufficient in number and have the skills and training to support people sensitively and effectively.

5.16 We need to take a systematic approach to understanding the communities we serve, who is over and under-represented in our services, and who has poorer experiences and outcomes. Actions to address discrimination and inequalities within services need to be taken in partnership with marginalised communities as described in the NHS England » Patient and carer race equality framework. Detailed information on and resources for advancing health equality are provided in Appendix 3.

“Every single person working in mental health has a role to play in making our services and systems fairer and challenging racism in all its forms.” Dr Jacqui Dyer, Mental Health Equalities Advisor, NHS England

6. Acute inpatient mental health care for adults and older adults

6.1 This section summarises the detailed guidance on ‘what good looks like’ in Acute inpatient mental health care guidance for adults and older adults, with emphasis given to the information of relevance to commissioners.

- Care is personalised to people’s individual needs, and mental health professionals work in partnership with people to provide choices about their care and treatment, and to reach shared decisions.

- Admissions are timely and purposeful – When a person requires care and treatment that can only be provided in a mental health inpatient setting and cannot be provided in the community, they receive prompt access to the best hospital provision available for their needs, which is close to home so that they can maintain their support networks and community links. The purpose of the admission is clear to the person, their carers, the inpatient team and any supporting services.

- Hospital stays are therapeutic – People receive timely access to the assessments, interventions, and treatments that they need, so that their time in hospital delivers therapeutic benefit. Care should be delivered in a therapeutic environment and in a way that is trauma-informed, working with people to understand any traumatic experiences they have had and how in hospital they can be supported in a way that minimises re-traumatisation.

- Discharge is timely and effective – People are discharged to a less restrictive setting as soon as the purpose of their admission is met and they no longer require care and treatment that can only be provided in hospital. For this to happen, discharge planning needs to start on admission. A range of community support available and supported living options also need to be available to meet different needs and enable people to maintain their wellbeing and live as independently as possible after discharge.

- Care is joined up across the health and care system – Inpatient services work in a cohesive way with partner organisations at admission, during a person’s inpatient stay and to support effective discharge, so that people are supported to stay well when they leave hospital.

- Services actively identify and address inequalities that exist within their local inpatient pathway, in partnership with people from affected groups and communities. This must include ensuring that people are not prevented from accessing or receiving good quality acute mental health inpatient care simply because of a disability, diagnostic label or any other protected characteristic.

- Services grow and develop the acute inpatient mental health workforce in line with national workforce profiles, so that inpatient services can offer a full range of multidisciplinary interventions and treatment. Staff wellbeing, training and development should be supported, so that inpatient services are a great place to work and staff are enabled to offer compassionate, high quality care.

- There is continuous improvement of the inpatient pathway – services strive to improve by making the best use of data, regularly developing, testing and refining change ideas using quality improvement methodology, and ensuring that service improvements are co-produced with people with experience of inpatient services and their carers

6.2 This section applies to all people who use acute inpatient services for adults and older adults including people with a learning disability and autistic people, people who have experienced trauma and people from racialised communities.

6.3 Further guidance on adjustments to acute mental health inpatient care for adults with a learning disability and autistic people can be found on the NHS England website including guidance on acute mental health inpatient services specifically for adults with a learning disability and autistic adults.

6.4 There are also tools such as the Green Light Toolkit that can help services think about the improvements that they could make to support people with a learning disability and autistic people.

6.5 In general, these specific acute mental health inpatient services will be staffed by specialist professionals with the skills and knowledge to deliver appropriate care and treatment to people whose needs would not be met in a mainstream service. For example, a multi-disciplinary team that includes registered learning disability nurses, and other clinicians with relevant expertise to support people with a learning disability and autistic people.

6.6 These services are also likely to have been designed specifically for people with a learning disability and autistic people in mind and therefore have more flexibility in terms of the environment and staffing requirements. This means offering a choice, e.g., of shared space and a cautious approach to environments that may become segregated ‘by default’ e.g., individual suites.

6.7 Specific policy requirements, guidance and resources relating to the care and treatment of people with learning disabilities and autistic people are detailed in Appendix 2.

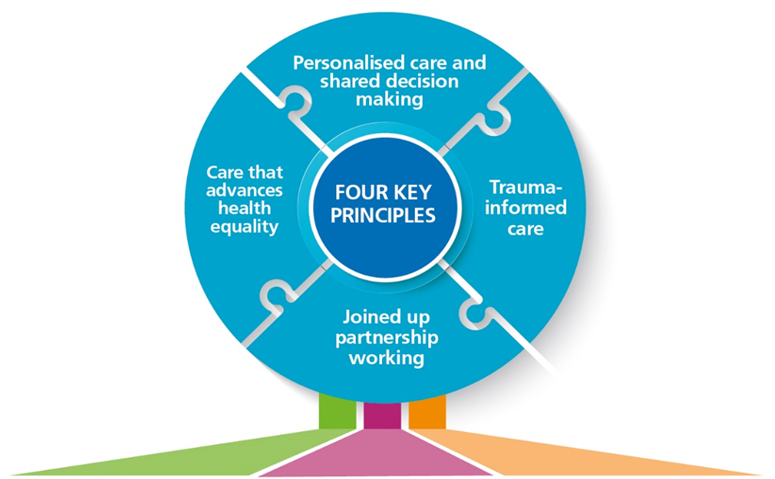

The following diagram illustrates the key elements that underpin effective acute mental health inpatient care. The 4 key principles and the 2 key enablers apply across the inpatient pathway and the 3 key stages relate to pre-admission, inpatient stay, and discharge.

Key elements of the inpatient pathway

Four key principles

- Personalised care and shared decision making

- Trauma-informed care

- Joined up partnership working

- Care that advances health equality

Three key stages

Purposeful admissions

People are only admitted to inpatient care when they require assessments, interventions or treatment that can be provided in hospital, and if admitted, it is to the most suitable available bed for the person’s needs and there is a clearly stated purpose for the admission.

Therapeutic inpatient care

Care is planned and regularly reviewed with the person and their chose carer/s, so that they receive the therapeutic activities, interventions and treatments they need each day to support their recovery and meet their purpose of admission.

Proactive discharge planning and effective post-discharge support

Discharge is planned with the person and their chosen carer/s for the start of their inpatient stay, so that they can leave hospital as soon as they no longer require assessments, interventions or treatments that can only be provided in an inpatient setting, with all planned post-discharge support provided promptly on leaving hospital.

Two key enablers

1. A fully multidisciplinary, skilled and supported workforce.

2. Continuous improvement of the inpatient pathway. Using data, co-production and quality improvement methodology.

Key stages of the acute inpatient pathway

Key stage 1. From the point of presentation to within 72 hours of admission

- Holistic assessment conducted to understand the person’s needs. This assessment should build on information contained within the person’s electronic patient record (EPR), including any recorded advanced choices and reasonable adjustments.

- Decision reached, considering as fully as possible the person’s preferences, including any advanced choice documents (ACDs), those of their chosen carer/s, and the views of relevant partner services, that the person’s needs can only be met in an inpatient setting and cannot be supported in the community. For people with a learning disability and autistic people, a care, education, and treatment review C(E)TR should take place pre-admission to support this decision (or if this is not possible, within 28 days of admission).

- Purpose of admission discussed and agreed with the person and their chosen carer/s and uploaded to the person’s electronic patient record (EPR).

- Prompt access facilitated to the most suitable hospital provision available for the person’s needs.

- Formulation review completed to gain an in-depth understanding of the person, the circumstances leading up to their admission and what will help them to recover.

- This, together with recorded ACDs and the findings of a C(E)TR (for people with a learning disability and autistic people), should be used as the basis to co-develop a personalised care plan with the person and their chosen carer/s, which should then be uploaded to the person’s EPR.

- Discharge planning begun with person and their chosen carer/s, including identifying any factors that could delay discharge (e.g., housing, social care), agreeing an estimated date of discharge (EDD) and an intended discharge destination, and uploading these to the person’s EPR.

- Interventions and treatment for physical and mental health conditions commenced or maintained, and a physical health check completed.

Key stage 2. During the hospital stay

- Daily reviews (e.g., using the Red to Green approach) completed to check the person is receiving prompt access to the assessments, interventions and treatment they require, in line with their purpose of admission and care plan. Assessments, intervention, and treatment should be adapted to meet reasonable adjustments and the needs of people from groups who experience health inequalities.

- Purpose of admission, care plan, discharge plan and EDD reviewed and updated regularly with the person and their chosen carer/s. If the purpose of admission is close to being met, additional focus should be given to discharge planning.

- Any factors that could delay discharge, (e.g., the need for step down provision, home adaptations, housing, supported living or care home placement) reviewed every two to three days and proactively addressed with partner services.

- Monitoring visits completed by commissioners every eight weeks for adults with a learning disability and autistic people, and every six weeks for young people aged up to 25, who have an Education, Health, and Care (EHC) plan.

Key Stage 3. At and following discharge

- Person centred discharge plan refined with the person and their chosen carer/s. The plan should set out who is responsible for providing the assessments, interventions, and treatments that the person will receive after leaving hospital and when the person can expect this support.

- Discharge facilitated promptly once a decision is reached that the person is clinically ready for discharge (CRFD) (i.e., the person does not require any further assessments, interventions and/or treatments, which can only be provided in the current inpatient setting), and that it is possible to discharge them (i.e. because the planned discharge support is available at that time). If a person is CRFD, but it is not possible to discharge them, they should continue receiving interventions, activities and support in hospital so that they remain CRFD and can be discharged as soon as planned support is in place.

- At least 48 hours’ notice of the decision to discharge given to the person, their chosen carer/s and any services (e.g., community based mental health and learning disability teams, Crisis Resolution Home Treatment Teams (CRHTTs), housing services, social services) that will be involved in the persons ongoing care.

- Risk assessment updated and uploaded to the person’s EPR which includes information on how any risks to self or others will be managed once the person is discharged.

- Follow up meeting arranged pre-discharge, including providing written details of when, where and who the follow up will take place with.

- Clear information provided to the person and their chosen carer/s about how to access crisis support after discharge (including direct contact details for CRHT.

- Prompt access provided to all planned post discharge support including in the person’s discharge plan. The person should also be supported to develop advanced choice documents and a crisis plan.

- Follow up completed (face to face wherever possible) within 72 hours of discharge for all adults discharged (NB this has been included in the NHS Standard Contract since 2020/21). If the follow up indicates additional support is required, action is taken promptly to put this in place.

- Relevant information relating to a person’s discharge (which may include a copy of the person’s discharge plan) shared with the services involved in the person’s ongoing care and treatment. Discharge summary shared with the persons GP and other relevant parties, where appropriate, within a week of discharge.

- Multi-Agency Discharge Events used where there are complex discharges requiring agreement across multiple partners and follow locally agreed escalation procedures where there are concerns about delayed discharges.

7. Adult mental health rehabilitation inpatient services

7.1 GIRFT (2020) Mental Health – Rehabilitation – Getting It Right First Time – GIRFT describes modern mental health rehabilitation as: “A whole system approach to recovery from mental ill health which maximises an individual’s quality of life and social inclusion by encouraging their skills, promoting independence and autonomy in order to give them hope for the future and which leads to successful community living through appropriate support.”

7.2 Wherever possible mental health rehabilitation needs should be met in the community. However, where someone’s needs exceed what can be safely and effectively treated in the community, admission to a mental health rehabilitation inpatient service may be required. This should always be local and consider the least restrictive option, which should be kept under review.

7.3 Mental health rehabilitation inpatient services provide care and treatment for adults and older adults who have an identified mental health rehabilitation need. This includes people who may also have a learning disability, who are autistic or who have been given a diagnosis of personality disorder. People may be detained under the Mental Health Act (1983), and some may be restricted under Section 37/41 (MHA). The decision to admit will be based on a comprehensive clinical assessment.

7.4 NICE (2009) Clinical guideline Borderline personality disorder: recognition and management) contain the following set of principles for mental health rehabilitation inpatient services, in that they should:

- Be embedded in a local comprehensive mental healthcare service.

- Provide a recovery-orientated approach that has a shared ethos and agreed goals, a sense of hope and optimism, and aims to reduce stigma.

- Deliver individualised, person-centred care through collaboration and shared decision making with service users and their carers involved.

- Be offered in the least restrictive environment and aim to help people progress from more intensive support to greater independence through the rehabilitation pathway.

- Recognise that not everyone returns to the same level of independence they had before their illness and may require supported accommodation (such as residential care, supported housing or floating outreach) in the long term.

7.5 This section summarises ‘what good looks like’ in mental health rehabilitation inpatient services, emphasising the information relevant to commissioners. It applies to all people who have a mental health rehabilitation need, including those with a learning disability, or who are autistic and those who have experienced trauma and those from racialised communities.

7.6 Each person is an individual and there may be other needs to consider in addition to the assessed mental health rehabilitation need. These may be relating to physical health, degenerative neurological conditions or acquired brain injuries for example. Commissioners should make commissioning decisions based on analysis of their local population need, size of population, historical activity, geography and accessibility.

7.7 It is important to note that there are currently some mental health inpatient services registered with CQC as ‘rehabilitation’ services, which are commissioned for people who have received a diagnosis of personality disorder, specifically a diagnosis of borderline personality disorder. The provision of such services is not in line with NICE guidelines for the care and treatment of people who have received this diagnosis and as per the recommendations of GIRFT national report for mental health rehabilitation, should not be described or commissioned as such. This misuse of the term ‘rehabilitation’ is unhelpful and confusing for everyone but particularly for the people themselves, their families and carers. The needs of this group who are currently being admitted to these types of services should be met locally, through co-produced alternative, community services which provide therapeutic, least restrictive and trauma informed care and support. Commissioners will want to consider the development of trauma-specific services to meet the needs of people who are currently admitted to these inpatient services given the majority of them will have experienced significant trauma and adversity.

7.8 However, the additional diagnostic label of personality disorder should not preclude admission where there is an identified mental health rehabilitation need. These commissioned services should not be overly restrictive and should focus on relational approaches to safety as the most effective way to keep the person safe.

7.9. The principles described in section 4 of this framework apply to all mental health rehabilitation inpatient services. The information that follows focusses on types of mental health rehabilitation inpatient services and stages of the pathway.

7.10. The variation in the language and terminology used to describe mental health rehabilitation inpatient services is confusing and persists despite previous attempts to tackle it. Stakeholders identified this as the most important issue to address in this guidance, the GIRFT report on mental health rehabilitation supports the need for clarification and ‘standardisation of rehabilitation care’.

7.11 Mental health rehabilitation inpatient services should be commissioned and described as:

Level 1 mental health rehabilitation inpatient services

Level 1 services have many of the characteristics of inpatient services described elsewhere/previously as ‘community rehabilitation units’ (Royal College of Psychiatry, 2019).

- These services are needs led and locally based, serving a local population.

- These services exist to meet the needs of people who have a mental health rehabilitation need that can only be treated within an inpatient environment.

- Level 1 services are normally accessed via an adult acute mental health inpatient service, including those specifically for adults with a learning disability, or who are autistic.

- As with adult acute mental health services, the default position for autistic people and those who have a learning disability, with a mental health need, would be to access mainstream mental health rehabilitation inpatient services. However, it is recognised that some people’s needs cannot be met well in a mainstream service, even with reasonable adjustments. Commissioned services may include mental health inpatient rehabilitation services that are specifically for people with a learning disability, or who are autistic.

- Level 1 services are part of a clear, agreed pathway that includes community mental health rehabilitation teams and wider general and specialist teams, such as primary care, community learning disability, autism or mental health

- They are staffed by a multidisciplinary team that have the appropriate training, skills and knowledge in mental health rehabilitation and should meet specialist need as required, for example, drug and alcohol support.

- These services should be firmly connected to the wider resources and agencies within the community, for example, employment support, housing and welfare.

Level 2 mental health rehabilitation inpatient services (higher support needs)

Level 2 services have many of the characteristics of services described elsewhere/previously as ‘high dependency rehabilitation units’ (RCPsych (2019).

- All the points above for level 1 services apply to level 2 services.

- Level 2 services neither support nor encompass inpatient provision that may be described as ‘locked rehabilitation’, and they are not long-term placements, continuing care, or a ‘home’ by default.

- The key difference between level 1 and level 2 mental health rehabilitation inpatient services is that a level 2 service can offer more intensive support to people to meet their needs; this may be relational and/or adapted environments and procedures.

- Commissioning arrangements for level 2 services will be locally determined and will depend on the size and assessed need of the population in each ICS footprint.

- Level 2 services are part of the same pathway of care as level 1 services and may on occasion be accessed via a level 1 service.

- Level 2 services may accept people who need their mental health rehabilitation needs met at a pace that is individually and clinically appropriate for them. These services should be commissioned to do this while ensuring that lengths of stay are appropriate and reviewed regularly, to avoid stays in hospital that are longer than absolutely necessary.

7.12 Commissioners must be clear, based on their population needs’ assessment, what services they need to commission and plan accordingly using this two-level approach for all mental health rehabilitation inpatient services. They should commission the right types of service to meet agreed local need.

7.13 It is important to note that services described as ‘locked rehabilitation’ are not mental health rehabilitation services and that these locked services remain a concern, as illustrated by these quotes:

“More than 50 years after the movement to close asylums and large institutions, we were concerned to find examples of outdated and sometimes institutionalised care. We are particularly concerned about the high number of people in ‘locked rehabilitation wards’… In the 21st century, a hospital should never be considered ‘home’ for people with a mental health condition.” (CQC, 2017)

“Too often, locked rehabilitation wards are in fact long stay wards that institutionalise rather than rehabilitate people and that such wards are against the least restrictive principle and potentially represents a breach of human rights.” (CQC (2020).

“I was put somewhere and left; I was forgotten about!” A person in a mental health rehabilitation inpatient service.

7.14 Similarly, the Royal College of Psychiatrists (RCPsych) has expressed its increasing concern about the use of locked rehabilitation wards, a term not recognised by the Rehabilitation or Social Psychiatry Faculty: “… there remain concerns about the high number of wards continuing to identify as ‘locked rehabilitation’. This goes against the least restrictive principle that mental health services should be using.” (CQC, 2020).

7.15 The case for change in relation to ‘locked rehabilitation’ services is clear and in future, the commissioning of services described as such should cease.

7.16 The impact of moving to this approach for the commissioning of mental health rehabilitation inpatient services will need to be assessed locally, and collaboratively planned and managed with relevant stakeholders. For example, in some areas this will need to include NHS-led provider collaboratives of adult secure services where ‘locked rehabilitation’ may for some people be accessed as part of the forensic pathway, or where an access assessment recommends it as an alternative to a secure service.

How should mental health rehabilitation inpatient services work?

7.17 A lot of work has already been undertaken to describe what good looks like in mental health rehabilitation inpatient settings, including published standards, guidance and reports (GIRFT, 2022; NICE, 2020 guideline [NG181]; Booker C, Rahman-Ali F, Paget S, eds, 2020; CQC, 2019). Commissioners should ensure that these are reflected in service specifications and contracts they hold with providers of mental health rehabilitation inpatient services.

7.18 Stakeholders described what they felt were the most important components of the inpatient service. These are described under the states of the inpatient pathway, they are included here to support commissioners and strengthen the existing published standards.

Assessment and admission

“Our son was admitted with 1 days’ notice from an acute mental health ward. This was the first time we knew a mental health rehabilitation ward was being considered.”Parents of a person in a mental health rehabilitation inpatient service.

7.19 Referrals to the service should state the reason for admission and the identified mental health rehabilitation needs, to support an appropriate assessment by the inpatient clinical team. Admissions should be planned, and pre-admission visits are considered good practice.

7.20 The purpose of admission should describe the specific assessments and interventions required, anticipated length of stay and estimated date of discharge. These should be agreed collaboratively at the earliest opportunity with the person accessing the service, their families and carers, the inpatient MDT, community team and commissioner. This information should be clearly articulated to make explicit what is expected from the admission.

Care and treatment

“I have had a good experience of reviews, the language used should be human, not clinical and not rushed”. Family member of a person accessing a mental health rehabilitation inpatient service.

7.21 All MDT ward rounds; care programme approach meetings and Care Education and Treatment Reviews must centre around the person. People in services should be supported and empowered to attend throughout and where possible to lead their reviews.

7.22 The purpose of admission, specific interventions required, anticipated length of stay and estimated date of discharge should be regularly reviewed, and changes to the original position should be clearly documented with reasons for the changes.

7.23 All therapeutic interventions and activities should focus on relationships, they should be holistic, needs led, trauma informed and diverse.

7.24 Activities and leave from the ward should be planned individually for each person. Structured activity programmes should be co-designed with people on the ward to ensure they reflect the activities they request, and feel will be helpful. Co-facilitation of activities and groups by people accessing services and staff are described positively by those leading sessions and those attending. Activities should happen in line with NICE guidelines and be available 7 days a week and not restricted, for example, to 9am to 5pm.

7.25 Vocational and employment opportunities are important to help people think about options, with an emphasis on appropriately knowledgeable and skilled staff providing education and support. Returning to their previous occupation is not an option for many people and therefore to help their recovery they will need to be supported to think about what transferrable skills they have.

7.26 Peer support should be encouraged; making friends in services is really important to people, their families and carers.

7.27 Appropriate and accessible support for substance misuse while an inpatient needs to be available.

7.28 Physical exercise options need to be individually planned and varied. These need to be available on and off the ward, accessible opportunities in the community are positive.

7.29 Primary and secondary physical health needs should be understood and met. People described a sense that not all staff were confident in this area and needed more appropriate training. Support while in hospital and a better understanding of how to self-manage physical health in the community is valued by people accessing these services.

Discharge and transition

7.30 Early discharge planning is crucial. Discussions about the purpose of admission, interventions required, length of stay and estimated date of discharge should inform this from the point of admission. In some instances, this may be considered earlier, at the point of the pre-admission assessment to inform the admission.

7.31 Transitions are difficult times for people, their family and carers; multiple transitions can be particularly problematic. Those accessing services feel it is important to maintain continuity by being able to work with some members of the MDT on an ongoing basis, from the inpatient service to the community. They also view contact with their community team, ideally a community mental health rehabilitation team, throughout admission as crucial to supporting and facilitating earlier and more collaborative discharge planning. People want gradual discharge planning and don’t want to feel rushed as this can be a particularly anxious time.

Key lines of enquiry for commissioners of local acute and rehabilitation inpatient services

Do you have services that:

- Serve everyone locally?

- Advance mental health equalities?

- Provide safe personalised care?

- Can be reasonably adjusted for autistic people and people with a learning disability?

- Are trauma informed?

- Enable shared decision-making?

- Offer independent advocacy?

- Offer therapeutic benefit to the people they serve?

- Connect to the whole care pathway so that all people can come into hospital when they need to and can leave as soon as they are ready?

Appendix 1: Policy context and system working

The NHS Long Term Plan (2019) heralded an unprecedented investment and expansion in mental health services, and set out a vision for a place-based community mental health model and whole-person, whole-population health approaches.

The task of modernising community services is supported by the Community mental health framework for adults and older people, the National Strategy for autistic children, young people and adults: 2021 to 2026, and Building the right support, the national plan for people with a learning disability and autistic people.

However, while maintaining a strong focus on community mental health transformation are at the heart of the NHS Long Term Plan and the Mental Health Implementation Plan (MHIP), the latter includes ambitions specific to inpatient services:

- Eliminate all inappropriate adult acute mental health out of area placements.

- Improve the therapeutic offer from inpatient mental health services by enhancing access to therapeutic interventions and activities.

- Increase the level and mix of staff on acute mental health inpatient wards, including improving access to peer support workers, psychologists, occupational therapists, social workers, housing experts and other relevant professionals during admission.

- Reduce avoidable long lengths of stay in adult acute mental health inpatient settings (including for people with a learning disability and autistic people), so that people are not staying in hospital any longer than necessary.

- Reduce the number of people with a learning disability and autistic people in mental health settings, so that by March 2024 there are no more than 30 adults with a learning disability and/or autism in an inpatient setting, per one million adults.

- Ensure that all inpatient care commissioned by the NHS meets the Learning Disability Improvement Standards.

Across the delivery of these commitments, consideration must also be given to reducing the associated inequalities, involving people in decisions about their care and adapting interventions and activities to meet individual needs and preferences.

Recent changes in legislation and organisation offer new potential for working in ways that promote collaboration and integration of services and support, including with the voluntary, community, faith, community and social enterprise (VCFSE) sector. Many people who experience inpatient services will need support beyond healthcare. This VCFSE sector has always supported the NHS, including by supporting community voices to be heard and being partners in strategy development.

Importantly, each system will also have provider collaboratives, which are partnerships of health providers who agree to work together to achieve benefits by working at scale for their population.

Appendix 2: Key resources

- NHS England Mental Health, Learning Disability and Autism Quality Transformation Programme

- NHS England position on serenity integrated monitoring and similar models

- How CQC identifies and responds to closed cultures

- CQC Mental health rehabilitation 2019 update

- GIRFT national report for mental health rehabilitation

- Safe and wellbeing reviews: thematic review and lessons

- Out of sight – who cares?

- Detentions under the Mental Health Act

- Independent review of the Mental Health Act

- Draft Mental Health Bill 2022

- Thematic review of Independent Care (Education) and Treatment Reviews

- The NHS Constitution for England

- Equality Act 2010

- Personalised care and support planning

- NHS England » Accessible Information Standard

- Delivering same-sex accommodation

Advancing mental health equalities

- NHS England » Patient and carer race equality framework

- Personalised care

- Working definition of trauma-informed practice

- Shared decision-making

- Advocacy services for adults with health and social care needs

NHS-led provider collaboratives

- FutureNHS Platform

- Learning disability improvement standards for NHS trusts

- NHS Mental Health Implementation Plan 2019/20 – 2023/24

- The NHS Long Term Plan

Community mental health framework

- The national strategy for autistic children, young people and adults: 2021 to 2026

- Building the right support

- NHS England 2023/24 priorities and operational planning guidance

- Health and Care Act 2022

- Section 75 of the National Health Act 2006

- Better Care Fund

- A shared commitment to quality for those working in health and care

Additional resources

- NHS England Care, Education and Treatment Reviews (CETRs)

- NHS England Dynamic support register and Care (Education) and Treatment Review policy and guide

- Rapid improvement guide to red and green bed days

- Safewards

- HOPE(S) Model: Mersey Care NHS Foundation Trust

- Blanket restrictions toolkit

- Debriefing guidance

- NIHR – The experience of children and young people cared for in mental health, learning disability and autism inpatient settings

- Our rights, our voices Young people’s views on fixing the Mental Health Act and inpatient care

- A review of advocacy – NDTi

- collaboRATE – measure of shared decision making in mental health care.

- National plan – Building the right support

- NHS Long Term Workforce Plan

Reducing health inequalities

- Ethnic inequalities in healthcare: A rapid evidence review

- NHS England » RightCare physical health and severe mental illness scenario

- Learning Disability Annual Health Check Toolkit – NDTi

- Green Light Toolkit – NDTi

- “It’s Not Rocket Science” – NDTi

- NHS England Sensory-friendly resource pack

Appendix 3: Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the essential support of the Commissioner Advisory Group (CAG) in producing of this framework:

- Sahil Dodhia (Co-Chair) – Mental Health, Learning Disability and Autism Quality Transformation Team, NHS England

- Debra Moore (Co-Chair) Mental Health, Learning Disability and Autism Quality Transformation Team, NHS England

- Tonita Whittier – Mental Health, Learning Disability and Autism Quality Transformation Team, NHS England

- Richard Watson – Suffolk and North East Essex ICB

- Claire Swithenbank – NHS England North West

- Giles Tinsley – NHS England Midlands

- Keir Shillaker – West Yorkshire Health and Care Partnership ICB

- Mel Watson – Midlands Partnership NHS Foundation Trust

- Gavin Thistlethwaite – NHS England South East

- Sarah Mansuralli – North Central London ICB

- Lauretta Kavanagh – North Central London ICB

- Lisa Ryland – NHS Hampshire and Isle of Wight ICB

- Mark Humble – North East Commissioning Support Unit

- Karen Drabble – Thames Valley and Wessex Adult Secure Provider Collaborative

- Catherine Nolan – Association of Directors of Adult Social Services

- Louise Davies – Independent Expert Advisor – Commissioning

- Di Domenico – Independent Expert Advisor – Commissioning

In addition, the guidance has built on broader engagement through workshops, stakeholder and task and finish groups and visits to inpatient services across the country. We are particularly grateful to the people with lived experience of mental health services and their families who gave their time and shared their stories, insights and expertise so generously.

Publications reference: PRN00145