Classification: Official

Publication reference: PR1103

Summary of actions

NHS England working in partnership with integrated care system (ICS) leads and representatives, has devised actions to help systems develop plans that can support people who are taking medicines associated with dependence and withdrawal symptoms. The actions will support ICSs to deliver on their 4 key objectives of:

- improving outcomes in population health and healthcare

- tackling health inequalities in outcomes, experience and access

- enhancing productivity and value for money

- helping the NHS support broader social and economic development.

The actions have been co-produced with a range of stakeholders including: patients with lived experience and groups representing them, charities and voluntary sector organisations, clinical experts and national organisations, for example NICE (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence).

Action 1 – Personalised care and shared decision-making

Embed person-centred care in ICS service specifications or development plans, to provide opportunities for healthcare professionals to practise personalised care, such as through dedicated clinics or using structured medication reviews (SMRs).

During regular medication reviews and when considering prescribing, healthcare professionals should openly discuss with the patient (with consideration for their health literacy):

- intended outcome from prescribing

- potential benefits, risk and harm of the treatment

- decisions about whether to continue, stop or taper treatment.

Action 2 – Alternative interventions to medicines

Offer alternative interventions and services, where appropriate, to patients when a prescription for a medicine associated with dependence and withdrawal symptoms is first considered, or when the prescription is reviewed.

Systems should ensure that alternative treatment options are available and that prescribers are aware of them.

Action 3 – Service specification and change management

Use system-level task and finish groups (or similar) to ensure appropriate commissioning of services for patients taking medicines associated with dependence or withdrawal symptoms, including services for patients wishing to reduce or stop these medicines.

Additionally, ensure that people with a role in service design, provision, monitoring and implementation have access to sufficient education and training on medicines associated with dependence and withdrawal symptoms, so they can meet their population’s needs.

Action 4 – Taking whole system approaches

Use a whole system approach and pathways involving multiple interventions, to improve care for people prescribed medicines associated with dependence and withdrawal symptoms. A service specification should set out the requirements for any commissioned services and should be produced in collaboration with other partners, including local authorities and third sector bodies.

For example, build into service specifications:

- appropriate services for patients experiencing withdrawal symptoms from deprescribing of these medicines

- alternative treatments and services for prescribers to offer the right type and level of support for patients

- a requirement to deliver local care using multidisciplinary teams

- a requirement to use data on prescribing and localised health inequalities (see action 5).

Action 5 – Population health management

Use primary care data on prescribing and localised health inequalities to:

- monitor access to services, patient experience and outcomes for communities within the integrated care system (ICS) that often experience health inequalities

- help local areas prioritise

- identify key lines of enquiry

- inform action plans that prioritise and support patients at greatest risk of dependence and withdrawal.

Ensure processes are in place to identify and review medicines of patients who may have been taking them for longer than the evidence suggests is helpful.

1. Introduction

We have developed this framework for action with and for integrated care boards (ICBs) and primary care in response to Public Health England’s (PHE) review recommendations (2019) and our subsequent analysis of data to 2020/21. We have worked with organisations including the Department of Health and Social Care, Care Quality Commission, Health Education England, NICE (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence) and the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency.

A range of stakeholder have been consulted including: patients with lived experience and groups representing them, charities and voluntary sector organisations involved in provision of services in this area, clinical experts and Royal Colleges.

The PHE review of data from 2008 to 2018, Dependence and withdrawal associated with some prescribed medicines: An evidence review (2019), identified that in England in 2017/18 one in four adults (aged 18 and over) were prescribed benzodiazepines, z-drugs, gabapentinoids, opioids for chronic non-cancer pain or antidepressants (see footnote 1). Since 2008 the number of patients dispensed either antidepressants or gabapentinoids had been increasing, with trends gradually decreasing for the other three classes (benzodiazepines, opioids or Z-drugs). Our review of more recent data (to 2020/21) shows these trends continue (see Appendix, footnote 2) with the exception of a plateau in the number of patients dispensed a gabapentinoid. Prescribing patterns for all five classes of medicines were higher in women and older patients, and in areas of deprivation

The PHE review also found that more people were being prescribed these classes of medicines inappropriately and often for longer than good practice guidance recommends. Medicines associated with dependence or withdrawal symptoms can harm patients if they are prescribed inappropriately; affecting their physical, emotional, social and sexual health. There is little evidence that antidepressants carry a risk of dependence, but it is recognised that they are associated with withdrawal symptoms.

The risks associated with not optimising these medicines include:

- dependence:

- no longer feeling the beneficial effects of the prescription

- continuing to take medication despite the underlying condition having resolved

- taking these medicines when evidence-based non-medicine alternatives may be equally or more effective and safer

- symptoms of withdrawal such as fatigue, aches and pains, sweating, anxiety and restlessness, insomnia, and stomach and bowel problems

- need to take other medicines to manage side effects

- developing harmful coping mechanisms, such as alcohol and other substance abuse

- developing other conditions such as depression.

Implementing the PHE review’s recommendations: taking a whole system approach

NHS England was asked by the Department for Health and Social Care (DHSC) to co-ordinate the implementation of the PHE review’s recommendations. Among these was that “Effective, personalised care should include shared decision-making with patients and regular reviews of whether treatment is working. Patients who want to stop using a medicine must be able to access appropriate medical advice and treatment, and must never be stigmatised”.

Personalised care means people have choice and control over the way their care is planned and delivered. It is based on ‘what matters’ to them and their individual strengths and needs; shared decision-making is a key component. Prescribers should ensure that patients have the capacity to enter into the shared decision-making process.

Implementation of the review recommendations to support patients prescribed medicines associated with dependence and withdrawal symptoms is complex and requires an integrated whole system approach, with engagement across systems, partnerships and organisations (including voluntary, community and social enterprise sector partners [VCSE], social care providers housing and education providers) and the criminal justice system. It should also take into account the recommendations from the National Overprescribing Review, as well as other sources of evidence and good practice:

- The NHS England Medicines Safety Improvement Programme (MedSIP) resources outlining whole system approaches to improving patient safety are available on the FutureNHS collaboration platform.

- NICE guideline NG215 Medicines associated with dependence or withdrawal symptoms: safe prescribing and withdrawal management for adults covers general principles for prescribing and managing withdrawal from opioids, benzodiazepines, gabapentinoids, Z‑drugs and antidepressants in primary and secondary care. Alongside this guideline, NICE has produced visual summaries of the recommendations for discussing starting a medicine and making a management plan and reviewing medicines.

- Other NICE guidelines:

- Chronic pain (primary and secondary) in over 16s: assessment of all chronic pain and management of chronic primary pain (NG193)

- Depression in adults with a chronic physical health problem: recognition and management (CG91)

- Depression in adults: treatment and management (NG222)

- Generalised anxiety disorder and panic disorder in adults: management (CG113)

- Neuropathic pain in adults: pharmacological management in non-specialist settings (CG173).

2. Purpose of this framework for action

The framework is for ICB leads and health and social care practitioners working in care settings where the five classes of medicines may first be prescribed.

It provides actions to optimise personalised care for adults who are prescribed medicines associated with dependence or withdrawal symptoms, by taking a whole system approach. ICBs should work with their partners and stakeholders, including people and communities, to implement these actions.

These actions can help to:

- Increase the reach of personalised care by:

- supporting provision of effective, personalised and tailored support services for people at risk of dependence or withdrawal from these medicines

- encouraging all levels of the system to support patients in making positive changes at every interaction, in line with the principles of making every contact count

- reinforcing the need for personalised care approaches that may or may not include the use of medicines

- encouraging the development of culturally competent communications and an engagement plan to reach all parts of the community.

- Optimise prescribing by:

- supporting strategic, operational and/or clinical decision-making

- reducing unwarranted variation in prescribing and in patient care

- signposting readers to tools and resources that aid identification of patients for review and support improved prescribing behaviours

- encouraging local systems to use the tools, data and information available to them to co-ordinate improvement.

Using the framework

Implementation and supplementary information is provided for each of the actions. An underpinning rationale sets out reasons why an action has been developed.

Case studies offer ICBs and local leaders insight into the range of approaches that can be offered to patients (they are not a blueprint for service development).

3. Actions to optimise personalised care

The NHS England change model is a framework that can be used for any project or programme that is seeking to achieve transformational, sustainable change. Implementing change should be underpinned by the four key principles for enacting successful change – leadership, multiprofessional working, access to data and education.

Optimisation approaches for these medicines should be prioritised in local integrated care system (ICS) improvement and delivery plans, including when:

- commissioning services

- developing local policies

- implementing in prescribing practice.

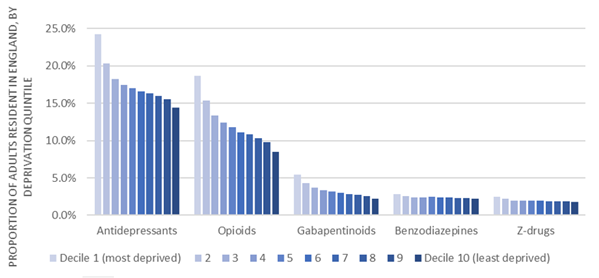

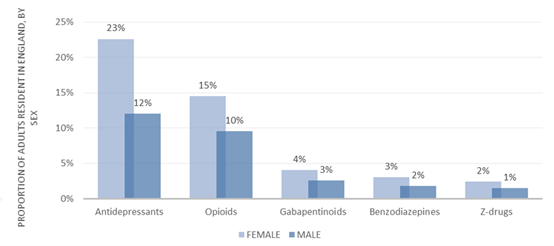

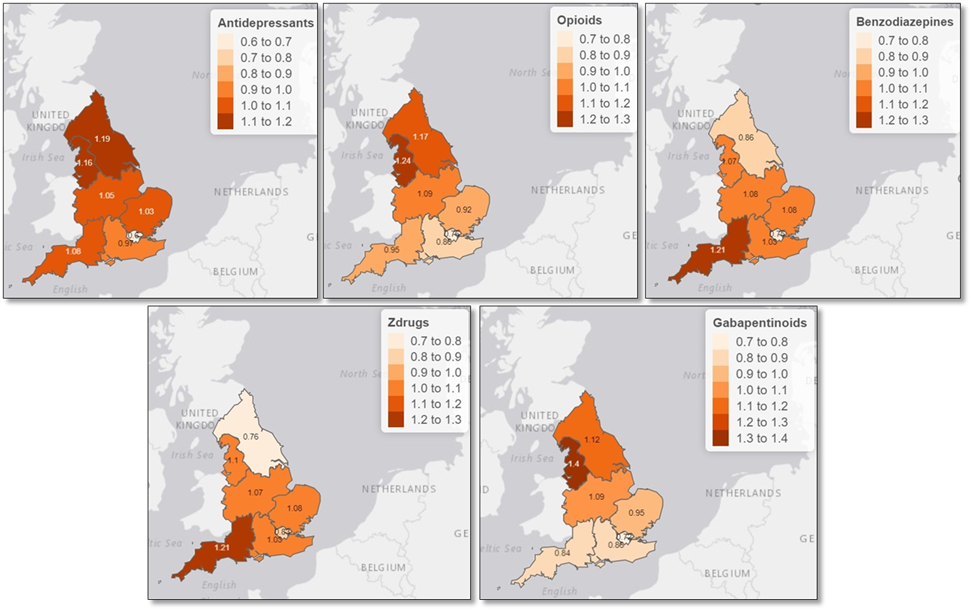

An important consideration will be narrowing health inequalities (see Appendix, Figures 1 to 3).

Action 1 – Personalised care and shared decision-making

Embed person-centred care in ICS service specifications or development plans, to provide opportunities for healthcare professionals to practise personalised care, such as through dedicated clinics or using structured medication reviews (SMRs).

During regular medication reviews and when considering prescribing, healthcare professionals should openly discuss with the patient (with consideration for their health literacy):

- intended outcome from prescribing

- potential benefits, risk and harms of the treatment

- decisions about whether to continue, stop or taper treatment.

Rationale: The NHS Long Term Plan sets out the commitment to multiprofessional working as well as use of ‘new roles’ in primary care, such as social prescribing link workers and clinical pharmacists. Multidisciplinary teams (MDTs) and these new roles will build capacity and increase the range of expertise to maximise quality of and enable a holistic approach to the patient’s care.

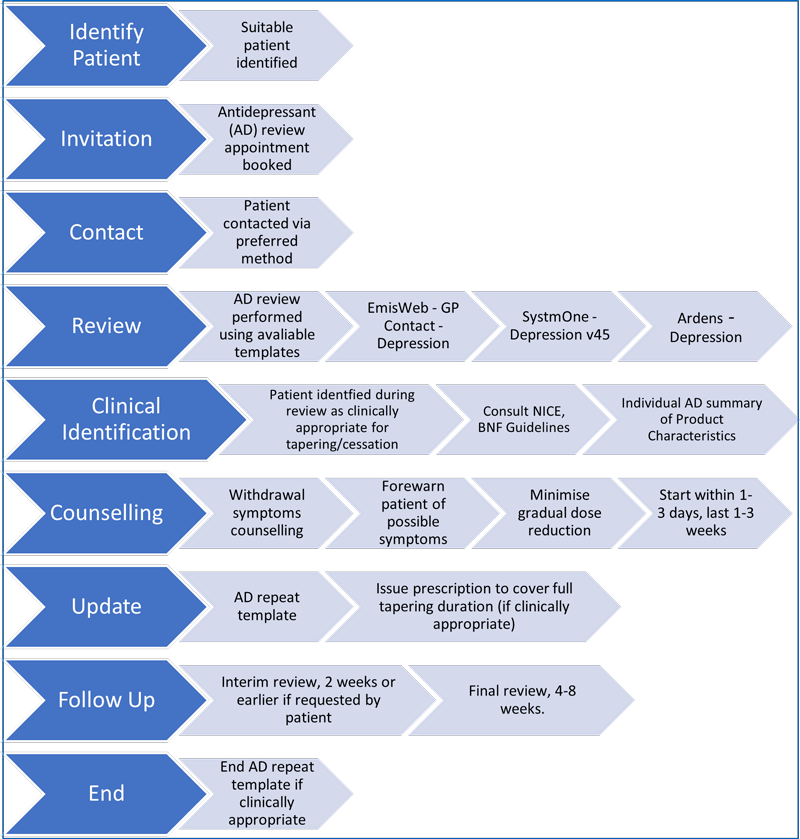

Prescribing and deprescribing decisions should be made jointly with the patient; their informed consent needs to be obtained and appropriate information on the risks and benefits of using the medicines given. A shared decision-making approach will help manage patients’ expectations about managing their pain and other symptoms.

Dependence forming medicines (DFMs) should never be stopped abruptly unless they have been taken for only a short time. As part of regular review, prescribers should discuss deprescribing with the patient if the:

- medicine is no longer benefiting the patient

- patient no longer wishes to take the medicines

- underlying condition has resolved.

The medicine dose may need to be tapered to manage and prevent withdrawal symptoms, depending on the dose the patient is taking, how long they have been taking the medicine for and other medico-social factors. Timescales need to be agreed between the patient and prescriber. A plateau in dose reduction or an increase in dose should not be deemed a failure in an individual’s deprescribing pathway.

The NICE guideline NG215 states “these medicines can provide lasting symptom management with a favourable balance of benefits and adverse effects for many people. But like all medicines, they do not work for everyone and can have negative consequences that outweigh their benefits. Even when people are not getting clinical benefit, these medicines may sometimes continue to be prescribed for various reasons, including concerns about the risk of unpleasant withdrawal symptoms or fear of worsening the underlying condition.”

Implementation: Ensure all aspects of care are accessible and sensitive to patients at risk of health inequity or inequalities. Services and/or pharmacological interventions should be based on the following principles:

- equitable access to local populations to avoid unwarranted variation

- culturally competent communications

- community based where possible

- communication focused decision-making.

Services should be designed to support people with complex and multiple needs, so broader needs, beyond those for patients who are taking medicines associated with dependence and withdrawal.

To embed shared decision-making, a MDT approach is needed with input from, for example, pain specialists, dependence services, mental health services and peer support groups. The MDT supporting people taking these medicines should include along with other healthcare professionals:

- social prescribing link workers

- clinical pharmacists

- community pharmacists

- first contact physiotherapists.

When discussing healthcare with patients, healthcare professionals need to keep in mind the diverse needs of local populations and that they need to check the patient understands the information they are communicating. A patient’s treatment plan should consider the patient’s needs, goals and expectations.

One of three new services introduced in the 2020/21 Network Contract Direct Enhanced Service and to be delivered by primary care networks (PCNs) from 1 October 2020 was SMRs and medicines optimisation. All PCNs are required to identify patients who would benefit from a SMR, including specifically those using potentially addictive pain management medication. The NHS England Quality and Outcomes Framework includes a quality improvement module to support improvements in:

- use of non-pharmacological alternatives rather than initiation of DFMs in line with best evidence and guidance

- SMRs of patients taking 120mg oral morphine equivalent (OME) or more for chronic pain

- SMRs where there is polypharmacy or inappropriate use of DFMs.

Additionally, two community pharmacy services can support patients on DFMs: NHS Discharge Medicines Service (NHS DMS) and the NHS New Medicines Service (NHS NMS).

NHS trusts can refer patients newly started on opioids (eg after surgery) and other medicines associated with dependence and withdrawal symptoms to the NHS DMS for review and follow-up by a community pharmacy, to minimise risk of long-term use and give patients extra support.

The NHS NMS supports people with long-term conditions newly prescribed certain medicines, which will generally help them to appropriately improve their medication adherence and self-manage their condition.

The Lived and Professional Experience Advisory Panel (LEAP) for Prescribed Drug Dependence can help and support NHS organisations or staff who when developing service specifications, development or action plans want to better understand what patients need. The panel have also produced multiple resources to support people who are taking medicines associated with dependence and withdrawal symptoms.

Resources

- Case study 1: NHS prescribed medication support service

- Case study 2: Recovery experience sleeping tablets and tranquilisers

- Case study 3: Pharmacy referral to liaison psychiatry service

- Case study 4: Benzodiazepine, opiate, gabapentinoid and Z-drug deprescribing (Benzodiazepines and Opioids Withdrawal Service)

- Case study 5: Alternatives to pharmacological interventions and appropriately commissioned services

- Case study 7: Patient safety card

- Antidepressants bulletin (PrescQIPP)

- Antidepressants initiation and review checklist (PrescQIPP)

- Antidepressant pathway (PrescQIPP)

- Communicating evidence in healthcare e-learning training package (The Winton Centre)

- Dependence and withdrawal forming medicines approval form A template letter for patients when a conversation about consent and risks associated with these medicines has been carried out (PrescQIPP)

- Health literacy e-learning training package for healthcare (NHS England and HEE)

- Live Well with pain has resources to help patients to self-manage their pain

- Lived and professional Experience Advisory Panel (LEAP) for Prescribed Drug Dependence (org)

- Medicines associated with dependence or withdrawal symptoms: safe prescribing and withdrawal management for adults (NICE)

- NHS Discharge Medicines Service – essential service, toolkit for pharmacy staff in community, primary and secondary care

- Personalised care e-learning packages (Personalised Care Institute)

- Person centred approaches – steps 1 and 2 (Skills for Health and HEE)

- Shared decision making E-learning programme (Centre for Pharmacy Postgraduate Education)

- Shared decision making implementation checklist (NHS England)

- Shared decision making summary guide (NHS England)

- Social prescribing link workers: reference guide for primary care networks (NHS England)

- Stopping antidepressants (Royal College of Psychiatrists)

Action 2 – Alternative interventions to medicines

Offer alternative interventions and services, where appropriate, to patients when a prescription for a medicine associated with dependence and withdrawal symptoms is first considered, or when the prescription is reviewed.

Systems should ensure that alternative treatment options are available and that prescribers are aware of them.

Rationale: Alternative treatments and services such as self-management approaches (social prescribing, health coaching, peer support, patient education), psychosocial interventions (psychotherapy), musculoskeletal clinics, mental health services (such as NHS Talking Therapies for Anxiety and Depression), pain clinics and sleep services can benefit patients and ensure a person-centred approach to care.

Social prescribing broadens access to the range of support available to people, which may help tackle health inequalities.

Implementation: Staff and systems should be aware of the alternative approaches available and recognise that people prescribed medicines associated with dependence and withdrawal symptoms may need to be managed differently from those dependent on other substances. Patients may benefit from concurrent interventions; for example, ongoing prescriptions for medicines and referral to a social prescriber.

An MDT approach with clearly defined roles and responsibilities should ensure prescribers have access to specialist advice for managing complex cases.

ICBs are encouraged to work with local authorities and VCSE and other organisations that provide psychosocial and non-pharmacological interventions.

Resources

- Case study 5: Alternatives to pharmacological interventions and appropriately commissioned services

- Case study 6: Living Well with Pain Programme

- About pain (patient information leaflet; Faculty of Pain Medicine)

- Chronic pain (primary and secondary) in over 16s: assessment of all chronic pain and management of chronic primary pain (NICE)

- Comprehensive model of personalised care (NHS England)

- Self-management navigator tool (for chronic pain) (Pain Concern)

- Thinking about opioid treatment for pain (patient information leaflet; Faculty of Pain Medicine)

- Tools to implement supported self-management (NHS England)

Action 3 – Service specification and change management

Use system-level task and finish groups (or similar) to ensure appropriate commissioning of services for patients taking medicines associated with dependence or withdrawal symptoms, including services for patients wishing to reduce or stop these medicines.

Additionally, ensure that people with a role in service design, provision, monitoring and implementation have access to sufficient education and training on medicines associated with dependence and withdrawal symptoms, so they can meet their population’s needs.

Rationale: System-wide task and finish groups can be used to understand the scale and causes of the issues, which will help to design and deliver local strategies, service specifications and action plans for delivering support to these patients. The groups can provide support for educating and raising awareness among patients and healthcare professionals.

Implementation: Task and finish groups should:

- Ensure appropriate commissioning of services for patients taking medicines associated with dependence and withdrawal symptoms based on local population needs, for example local services providing NHS Talking Therapies for Anxiety and Depression and other mental health services.

- Include representation from pain specialists and their teams, mental health services, personalised care leads and health inequalities leads.

- Develop systems and processes for:

- identifying all patients taking medicines associated with dependence and withdrawal

- prioritising patients for review (using local data), including those patients who may be at risk or who may soon be at risk without intervention

- how to review these patients

- auditing prescribing of adult patients (ideally involving the PCN clinical lead or pharmacist)

- safe withdrawal and stopping of these medicines where appropriate.

- Develop strategies and service specifications, and deliver action plans that enable commissioning of services that address local population needs for patients who are taking medicines associated with dependence and withdrawal symptoms.

- Develop referral pathways (for example, to social prescribing teams, specialist pain services or musculoskeletal services) for non-drug interventions where appropriate:

- for patients newly started on medicines associated with dependence and withdrawal

- for patients at review stage where non-drug alternatives and withdrawal services can be offered

- include signposting to these services for healthcare professionals to follow

- consider how the services can be publicised locally to reach all members of the community.

- Identify actions and responsibilities for the relevant pharmacist or clinical lead, prescriber and patients.

- Ensure wider needs of patients taking these medicines are considered (using Joint Strategic Needs Assessment and pharmaceutical needs assessments processes).

- Identify clinical champions to take actions forward.

Resources

- Case study 4: Benzodiazepine, opiate, gabapentinoid and Z-drug deprescribing (Benzodiazepines and Opioids Withdrawal Service)

- NICE clinical knowledge summaries include:

- PrescQIPP: Resources that allow ICBs to benchmark prescribing behaviours:

- A guide to Improving Access to Psychological Therapies services (NHS England)

- Mental Health Investment Standard (MHIS): Categories of mental health expenditure (for commissioning of NHS Talking Therapies for Anxiety and Depression) (NHS England).

Action 4 – Taking whole system approaches

Use a whole system approach and pathways involving multiple interventions, to improve care for people prescribed medicines associated with dependence and withdrawal symptoms. A service specification should set out the requirements for any commissioned services and should be produced in collaboration with other partners (including local authorities and third sector bodies).

For example, build into service specifications:

- appropriate services for patients experiencing withdrawal symptoms from deprescribing of these medicines

- alternative treatments and services for prescribers to offer the right type and level of support for patients.

- a requirement to deliver local care using multidisciplinary teams

- a requirement to use data on prescribing and localised health inequalities (see action 5).

Rationale: A whole system approach increases the opportunity to target resources towards those patient groups most in need; tackling the inequitable distribution of harm associated with opioids and unwarranted variation. It needs to be delivered over a number of years to achieve improvements of a sufficient scale and that are sustainable.

ICSs have responsibility to lead improvements in the quality and safety of care provided to their populations.

Brief interventions by the person’s general practice team during a consultation can contribute to improvement. Some people will respond to simple advice and guidance; perhaps given in the form of a letter signposting them to resources such as My Live Well with pain.

Some patients may wish to safely reduce their prescribed medicines and they should be supported to do so. They should have access to appropriate specialist advice (from an MDT) as withdrawal symptoms will not be identical for the five medicine groups, and some patients may be prescribed more than one of these medicines or need extra support when tapering their medicine.

Implementation: One example of a whole system approach is in the National Patient Safety Improvement Programme, which is using a 7 phase process to deliver the opioid safety initiatives. The programme analysed 112 case studies identified by patient safety collaboratives in late 2021/22 as describing interventions to reduce avoidable harm associated with the prescribing of opioids in chronic non-cancer pain. They found that a whole system and stratified approach to personalising care, delivered over a number of years, builds capacity and capability to meet people’s needs wherever they are on their pain management pathway. Case studies and examples to show the benefit and outcomes of this approach are available on the NHS England Medicines Safety Improvement page on the FutureNHS collaboration platform.

ICBs should:

- Work with other agencies, partners and VCSE organisations

- Consider the development and implementation of a range of treatment options for local populations and patients as part of their action and delivery plans

- Consider providing a range of withdrawal services; different services will best meet the needs of different cohorts of patients. Patients newly diagnosed with conditions that are often managed by the five classes of medicines can then be offered non-pharmacological interventions where appropriate, on their own in the first instance or alongside medicines

- Consider delivering localised services over the scale of a PCN and offering support for tapering along with signposting to biopsychosocial interventions; this can support many patients to reduce their doses or stop taking these medicines

- Have a clear referral pathway for these services from primary and secondary care

- Support clinicians to adopt new prescribing practices.

Other collaborations to support implementation include:

- Regional and ICB chief pharmacists and regional controlled drugs accountable officers actively engaging with services and improvements at a local level

- Primary care services, clinical and community pharmacists and GPs working together to support the needs of people experiencing these problems by ensuring they develop their knowledge and/or competence to identify, assess and respond to these groups of patients

- Services at place level, providing a selection of support (including a multidisciplinary team, a PCN service, a review by a clinician in general practice and supported self-care) will support many different patients. Additionally, specialist knowledge of dependence and chronic pain within these services will benefit those patients with the most complex needs.

Resources

- NHS England Medicines Safety Improvement page on the FutureNHS collaboration platform

- Case study 1: NHS prescribed medication support service

- Case study 2: Recovery experience sleeping tablets and tranquilisers

- Case study 3: Pharmacy referral to liaison psychiatry service

- Case study 4: Benzodiazepine, opiate, gabapentinoid and Z-drug deprescribing (Benzodiazepines and Opioids Withdrawal Service)

- Dependence and withdrawal forming medicines approval form – a template letter for patients when a conversation about consent and risks associated with these medicines has been carried out (PrescQIPP)

Action 5 – Population health management

Use primary care data on prescribing and localised health inequalities to:

- monitor access to services, patient experiences and outcomes for communities within the ICS that often experience health inequalities

- help local areas prioritise

- identify key lines of enquiry

- inform action plans that prioritise and support patients at greatest risk.

Ensure processes are in place to identify and review medicines of patients who may have been taking them for longer than the evidence suggests is helpful.

Rationale: Data enables users to:

- understand the prevalence and prescription duration (as a proxy for dependence and withdrawal risk)

- monitor changes in dispensing patterns

- monitor uptake of alternative treatment referrals.

Patients taking medicines associated with dependence or withdrawal need to be identified, and among these those who are high risk should be prioritised for review, including where appropriate a SMR. Early identification and review can prevent acute use of these medicines becoming chronic use (specifically with opioids).

Data from the English Dispensing Dataset (EPD) from the Opioid Prescribing Comparators dashboard (NHS Business Services Authority [BSA]) can be used to review up-to-date data, highlight variation and support local work to reduce harm from the prescribing of DFMs, as well as equip users with the tools for ongoing monitoring. The dashboard will be continually reviewed and updated with more metrics and views.

Many resources and tools are available to support prescribers and users of medicines associated with dependence or withdrawal symptoms. Their use should be embedded in local processes and services.

These medicines are usually used for chronic, complex and difficult to treat conditions, such as anxiety and insomnia, chronic pain including neuropathic pain, depression and generalised anxiety disorder. Patients taking medicines associated with dependence and withdrawal symptoms need to be identified to allow their medicines to be reviewed and appropriately managed.

The NICE guideline Depression in adults: treatment and management states that patients should be reviewed six months after being prescribed an antidepressant. Modelling using patient-level data shows that if a patient is on an antidepressant for at least three months, the likelihood they will stay on an antidepressant steeply increases. The longer patients continue on antidepressants the less likely they are to taper off (85% probability of staying on at the one-year mark, increasing to >90% two years in).

Implementation: Targeted metrics have been developed to enable ICBs to identify trends in the use of the five classes of medicines associated with dependence or withdrawal symptoms. The Opioid Prescribing Comparators dashboard (NHS BSA) is the first to make use of the live electronic prescribing system (EPS) data. Timely data will enable users to identify patients at risk of dependency much earlier. The analysis can be viewed at various geographical levels of the health system (including at practice, PCN, SICBL (sub-ICB locations), ICB, AHSN, region and national levels) and as comparative views or detailed demographic drill downs. The dashboard will be continually reviewed and updated with more metrics and views.

Clinical insight and local system knowledge will be needed along with data to determine whether deviation from the national average is unwarranted.

By accessing and using resources (including those listed below) prescribers can ensure that they have the skills, knowledge and competency to support people who are taking these medicines. This includes knowing what approaches to take for individual patients (through shared decision-making) and when to refer to other people in the MDT or other services. The National Medicines Safety Improvement Programme is launching a targeted suite of resources relating to the use of opioids in partnership with patient safety collaboratives and ICBs, to drive action locally within communities and populations.

A patient’s social, emotional, physical and mental wellbeing should be assessed, including by looking for symptoms of dependence or withdrawal, as the symptoms of their condition (eg pain) may affect activities of daily living.

Community pharmacists have a role in identifying people who have been on these medicines for longer than a specified time. They can review them or refer them to their general practice team for this. Community pharmacists are also well placed to identify people who are self-medicating to deal with the harms from taking these medicines.

Resources

- Case study 1: NHS prescribed medication support service

- Case study 2: Recovery experience sleeping tablets and tranquilisers

- Case study 3: Pharmacy referral to liaison psychiatry service

- Case study 4: Benzodiazepine, opiate, gabapentinoid and Z-drug deprescribing (Benzodiazepines and Opioids Withdrawal Service)

- Case study 5: Alternatives to pharmacological interventions and appropriately commissioned services

- Case study 6: Living Well with Pain Programme

- 2021/22 Network Contract Directed Enhanced Service (DES) Specification, which states that PCNs must have due regard to this guidance when delivering the service

- net provides a search interface onto the raw English Prescribing Dataset published by the NHS Business Services Authority. It is produced by the Bennett Institute for Applied Data Science, University of Oxford.

- Opioid prescribing comparators dashboard (NHS BSA)

- Addiction, misuse and dependency: A focus on over-the-counter and prescribed medicines (e-learning programme; Centre for Pharmacy Postgraduate Education)

- Anaesthesia programme (e-learning training modules; Royal College of Anaesthetists and HEE)

- Benzodiazepines: How they work and how to withdraw (The Ashton Manual)

- Controlled drugs in chronic pain: supporting patients with safe and effective use, e-learning programme (Centre for Pharmacy Postgraduate Education)

- Dependence forming medication (DFM) training module (PrescQIPP)

- E-pain (e-learning training modules; Faculty of Pain Medicine, The British Pain Society and HEE)

- General Medical Council (GMC) Good practice guidelines

- Maudsley prescribing guidelines An evidence-based handbook on the safe and effective prescribing of psychotropic agents

- Opioids (Centre for Pharmacy Postgraduate Education; only open to GPhC registrants)

- Opioids aware (Faculty of Pain Medicine)

- Opioid prescribing for chronic pain (NHS England South West Region)

- Pain pathway (PrescQIPP)

- Pregabalin and gabapentin: advice for prescribers on the risk of misuse (PHE and NHS England)

- Psychotropic drug directory Handbook for clinicians

- Structured medication reviews and medicines optimisation 2021/22 – sets out the required service changes from April 2021, as per the requirements in the 2021/22 Network Contract Directed Enhanced Service (DES) Specification

Conclusion

We have listened to what is important to patients who have experienced dependence and withdrawal from their prescribed medicines, co-producing actions which aim to improve patient outcomes, reduce harm and narrow health inequalities.

To make a difference, these actions need to be effectively prioritised in ICS improvement and delivery plans, including when commissioning services and developing local policies.

We ask that this framework for action is considered by ICBs and primary care, to ensure that personalised care for adults prescribed medicines associated with dependence or withdrawal symptoms is effectively optimised to ensure the best outcomes for patients, carers and the NHS.

Appendix: Prescribing patterns

All graphs and figures below have been developed by NHS England analysts using data from the NHS Business Services Authority and Office for National Statistics.

Health inequalities in 2020/21

Prescribing of antidepressants and opioids is noticeably higher in the most deprived Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) decile compared to the least deprived decile (9.8% and 10.1% higher respectively).

Prescribing rates for women are higher than for men across all five classes of medicines, with the largest difference for antidepressants (23% vs 12%).

All five classes of medicines are prescribed at levels higher than expected across most regions of England.

The five classes of medicines

Antidepressants

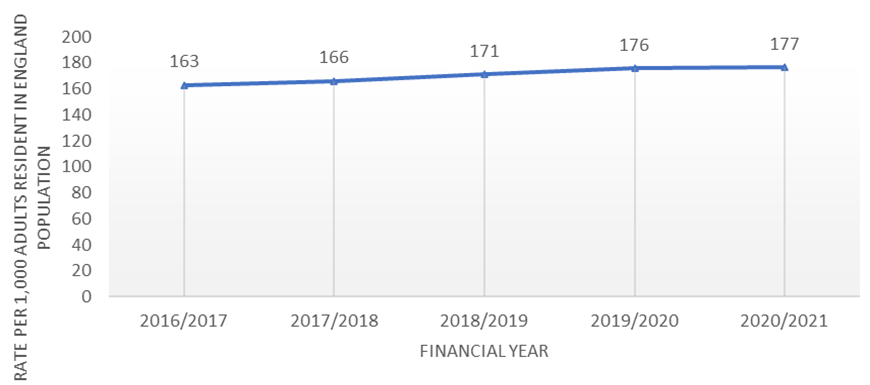

In 2020/21 7.9 million adults (177 per 1,000) were prescribed at least one antidepressant, an 8% increase from 2017/18.

Data available at the time of writing does not show that the COVID-19 pandemic has had an impact on the dispensing of antidepressants due to, for example, reduced NHS capacity to review patients on antidepressants or reduced provision of non-pharmacological alternatives.

The number of items prescribed has seen an increase over time; however, since 2017/18 the number of items prescribed has increased faster than the number of patients, which may imply the ratio of average number of antidepressant items prescribed per patient has increased.

Of patients currently on antidepressants, a third have been so for one year or less and two-thirds for over a year – and a third of the latter for four or more years.

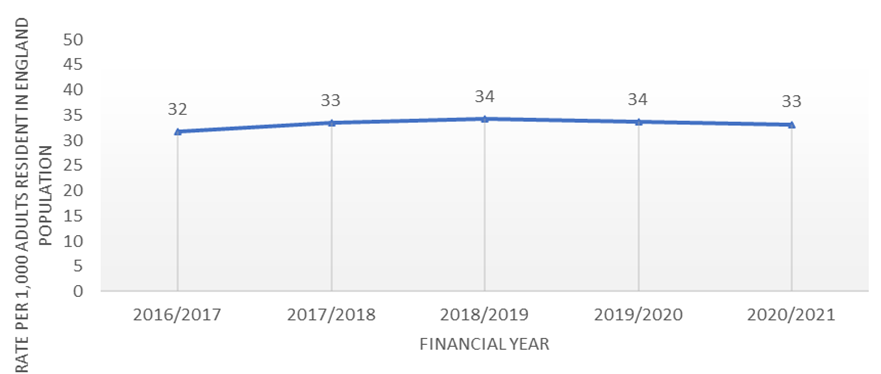

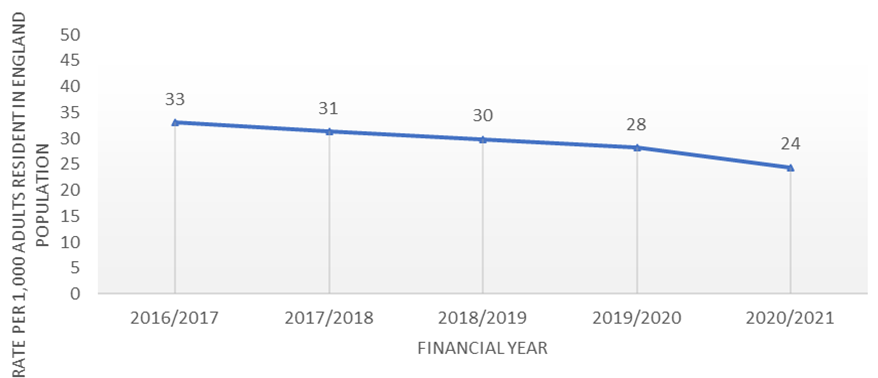

Figure 4: Antidepressant prescribing rates for adults in primary care in England, 2016/17 to 20201/212

Figure 5: Number of adults dispensed an antidepressant in primary care and number of items dispensed in England, standardised for adult resident population, 2016/17 to 2020/21

Benzodiazepines

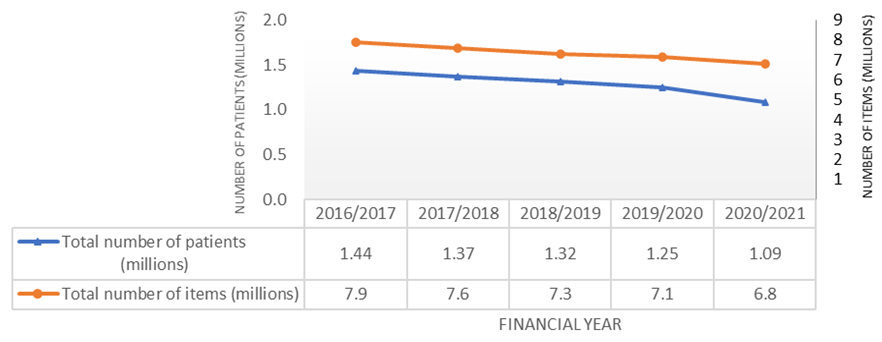

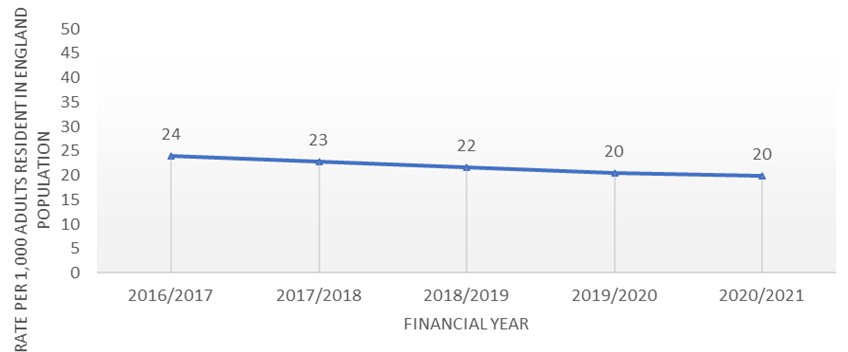

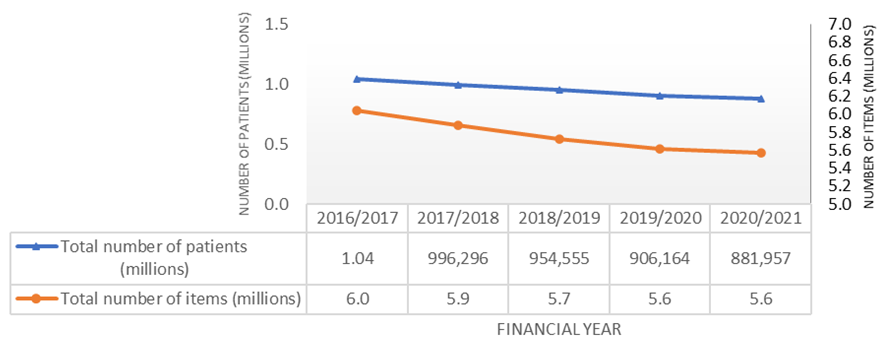

Between 2017/18 and 2020/21, the number of patients prescribed a benzodiazepine has reduced from 1.4 million to 1.1 million (20%). In 2020/21, 24 of every 1,000 adults in England (2.4%) were prescribed at least one benzodiazepine (a reduction from 31 per 1,000 [3.1%] in 2017/18). The overall number of items prescribed has also shown a downward trend, but the average number of items per patient increased in 2020/21 to 6.3 from a plateau of 5.5.

Benzodiazepines use shows an inverse relationship with deprivation, with prescribing rates slightly lower in areas of higher deprivation.

Figure 6: Benzodiazepine prescribing rates for adults in primary care in England, standardised for adult resident population, 2016/17 to 2020/21

Figure 7: Number of adults dispensed a benzodiazepine in primary care and number of items dispensed in England, 2016/17 to 2020/21

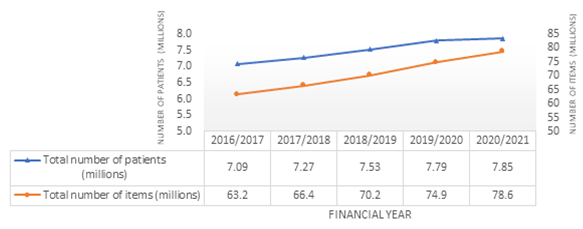

Gabapentinoids

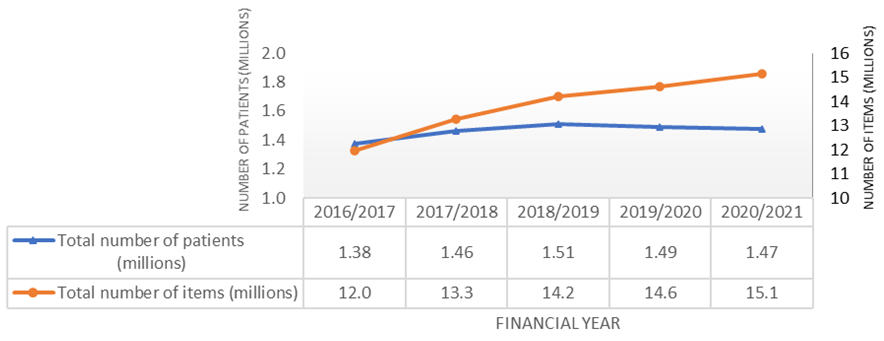

There has been a steady increase in the number of patients prescribed a gabapentinoid, increasing by about 11,000 (0.7%) a year, to just under 1.5 million patients since 2017/18. This gradual increase has also been seen in the number of items prescribed.

The number of patients prescribed a gabapentinoid has stabilised over time, resulting in an increase in the average number of items per patient from 8.7 in 2016/17 to 10.3 in 2020/21.

We are analysing prescribing patterns to identify any association with the change in gabapentinoid classification to Schedule 3 controlled drugs. To ensure any impact of legislation on the prescribing of gabapentinoids is being captured and monitored accurately, a data working group is exploring a metric to capture high and low dose pregabalin and gabapentin use, both in terms of number of people prescribed these medicines and quantity.

Prescribing data up to and including Q2 2020/21 shows a steady increase in prescribing of these medicines, with the number of patients prescribed a gabapentinoid increasing by about 57,000 to just over 1.1 million since Q1 2018/19 (23.9 to 25.1 adults per 1,000 population). There is concern that this increase in use of gabapentinoids is in response to decreasing trends in opioid prescribing.

There is a strong association between deprivation and gabapentinoid prescribing, with prescribing higher in areas of higher deprivation.

Figure 9: Gabapentinoid prescribing in primary care and number of items dispensed in England, 2016/17 to 2020/21

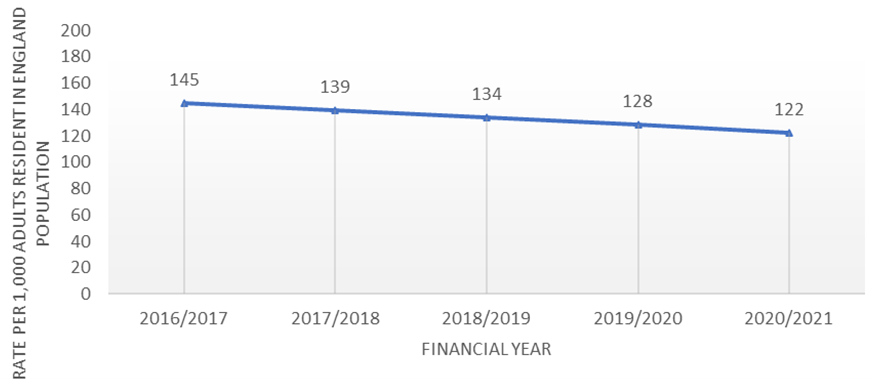

Opioids

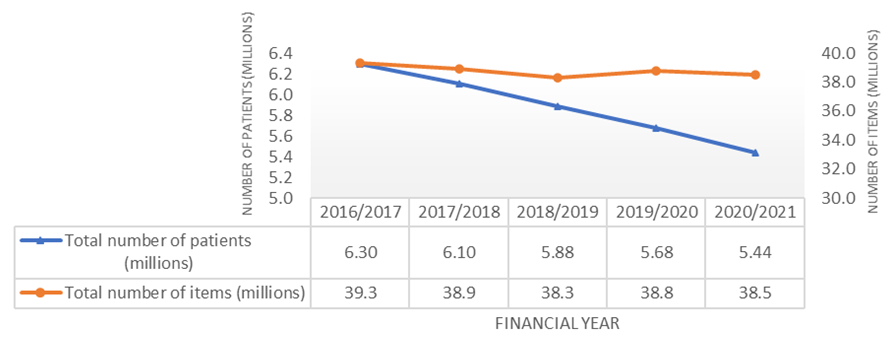

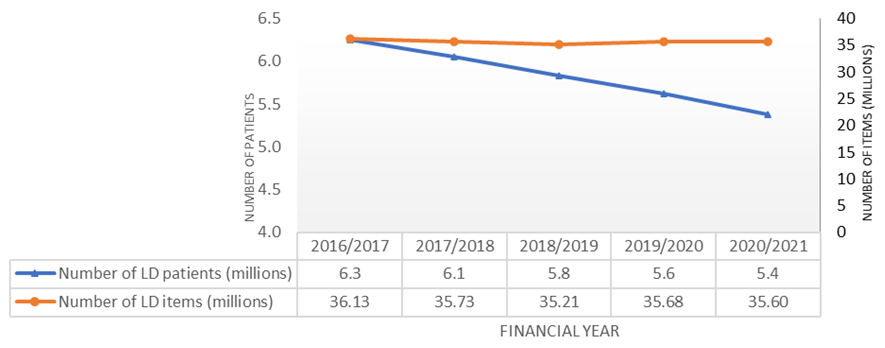

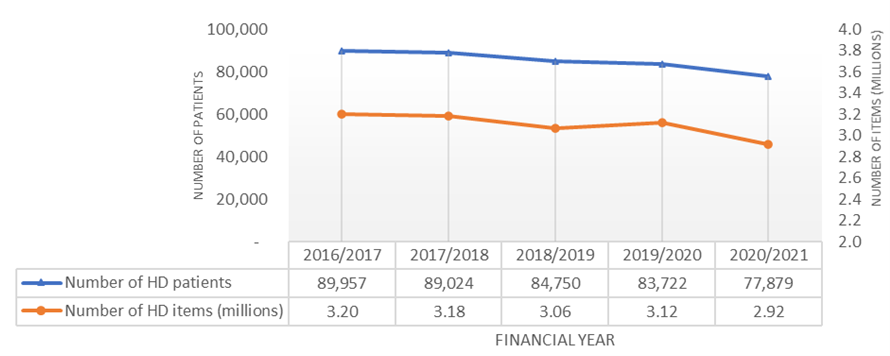

The number of patients dispensed an opioid continues to decline: 5.4 million in 2020/21 (122 per 1,000 adults in England), a decrease of about 11.5% from 6.1 million patients in 2017/18 (139 per 1,000 adult population). However, the average number of items dispensed has not shown a parallel decline and has steadily been increasing.

Almost all (99%) patients on opioids are on a low dose.

Prescribing of high dose opioids continues to decline – the number of patients prescribed a high dose opioid decreased by 4.8%, 1.2% and 7.0% respectively in the three years between 2017/18 and 2020/21.

The number of patients prescribed a high dose opioid does not appear to have increased during the height of the pandemic. In 2020/21 the number of high dose items prescribed decreased by about 6.5%; however, the average number of high dose items per patient has increased from 35.6 in 2019/20 to 37.5 in 2020/21.

Prescribing of low dose opioids has increased – the number of patients prescribed a low dose opioid has increased by 3.5%, 3.6% and 4.3% respectively in the three years between 2018/19 and 2020/21. The average number of low dose opioid items per patient has increased from 5.8 in 2016/17 to 6.6 in 2019/20.

Most patients remain on the same dose from one quarter to the next with only a small proportion escalating to a high dose, with most of the latter (78%) then remaining on the high dose into the next quarter.

Prescribing data shows that about 350,000 patients are initiated on opioids each quarter, the vast majority of whom (92%) stop treatment within a year. The probability of staying on an opioid once started increases from 27% at initiation to 79% within 12 months. A small proportion of patients remain on opioids for several years.

Figure 12. Low dose (LD) opioid prescribing in adults in primary care in England, 2016/17 to 2020/21

Figure 13: High dose (HD) opioid prescribing in adults in primary care in England, 2016/17 to 2020/21

Z-drugs

Z-drug prescribing continues to decline. In 2020/21 20 in every 1,000 adults in England (2%) were prescribed at least one Z-drug (a 2.3% reduction since 2017/18). The COVID-19 pandemic again does not appear to have had a noticeable effect on prescribing rates.

The number of items prescribed has declined at a slower rate, suggesting the average number of items per patient is gradually increasing.

There is an inverse relationship with deprivation levels, with areas of higher deprivation showing lower rates of prescribing.

Case study 1: NHS prescribed medication support service

Betsi Cadwaladr University Health Board, North Wales

The service

The NHS Prescribed Medication Support Service (PMSS) offers a personalised service that supports patients to withdraw from prescribed medications. The service responds reactively to referrals but also proactively identifies patients who may be dependent and benefit from withdrawing from their prescription.

The PMSS offers different levels of intervention depending on the individual patient’s needs, including:

- a holistic assessment

- SMART goal setting and achievable care planning

- education about improving health and wellbeing, eg sleep hygiene, diet and coping skills

- bespoke individual reducing programmes

- counselling, based on the cycle of change and motivational work

- auricular acupuncture

- advice/signposting to other services

- telephone support

- follow-up clinics in GP surgeries or community mental health bases

- pill cutters and plan packs

- preventative work.

Referrals can be made by:

- SPOA (single point of access)

- GPs, community mental health, community pharmacists, other primary care professionals

- open referral policy, including self-referrals.

Workforce

- Prescribed medication therapists (nurse/counsellors) – a dedicated role. They:

- must be registered or accredited with the Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC), British Association for Counselling and Psychotherapy (BACP), UK Council for Psychotherapy (UKCP), Association for Counsellors in Primary Care (CPC) or The British Association for Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapies (BABCP)

- are based in GP surgeries and build strong relationships with practice staff

- work with pharmacists and GPs to identify and contact patient groups; for example, pregnant women taking certain prescribed drugs, older patients who have had a fall and patients being prescribed drugs beyond guideline recommendations.

Outcomes

- Population of 701,000 across six counties.

- Cost per annum: £179,000.

- Cost per head of population: £0.26 a year.

- Cost per person experiencing intervention: £272.

- In the six months between April and September 2018:

- 329 people used the service (260 new referrals)

- 62% were reducing prescribed medications

- 33% ceased taking prescribed medications.

Factors for success

- Trained and experienced staff in a role bespoke to treating patients prescribed medicines associated with dependence and withdrawal symptoms.

- Collaborative and multidisciplinary working.

- The prescribed medication therapists run workshops for local general practices, pain clinics and other key stakeholders. This generates awareness of the service.

- Principles of shared decision-making.

- Stakeholder engagement.

Case study 2: Recovery experience sleeping tablets and tranquilisers

Camden and Islington community service

Recovery Experience Sleeping Tablets and Tranquilisers (REST) is a benzodiazepine support service delivered by Change Grow Live, a national voluntary sector organisation, for people in Camden and Islington seeking to stabilise/reduce/withdraw from use of benzodiazepines and Z-drugs. The service provides psychosocial interventions including individual and group counselling with support groups, education, guidance and advocacy. The programme is delivered as part of the local substance misuse offer.

This service was established in response to the experiences of people who had been prescribed benzodiazepines/Z-drugs and become dependent on or otherwise harmed by the medication. Many were dissatisfied with the information they were given about risks/side effects, felt let down by clinical services and did not consider GPs were offering them sufficient support. Also, they did not consider mainstream/general substance misuse services were always right for them or able to fully support their specific needs.

The service

The service is designed and delivered according to a reactive peer community service model. Individuals can self-refer or be referred by other local services such as homelessness projects, substance misuse services or mental health services.

Once referred, patients have a brief assessment to determine their needs. Patients can access these interventions through the service:

- helpline and drop-in support for general enquiries, including 1:1 tapering advice

- counselling referral, usually for 12 sessions, which includes tapering support

- peer support group – information and advice, plus encouragement and support, helping to reduce isolation and tackle stigma

- family support group – information and support for affected families

- referral to local Change Grow Live recovery support options, including RELEASE, women’s group, mindfulness, sleep clinics and foundations of recovery

- referral/signposting to other services where needed

- support to work with their GP to reduce/withdraw

- support into volunteering opportunities.

REST has established good links with a wide range of stakeholders to ensure referral pathways to the service are available, including from local GPs, community mental health teams, homelessness projects, drug and alcohol projects, and mental health services.

REST works closely with services where it can support recovery. For instance, service support staff may attend clinical meetings with Change Grow Live clinical staff or meet local mental health organisations to discuss delivery options to manage the mental health challenges that may come with benzodiazepine reduction/withdrawal.

Workforce

REST is staffed by an MDT including clinicians and support workers who work in a community setting.

Outcomes

- Cost per annum: £56,000.

- The service is delivered by:

- 1 counsellor, 3 hours a week (voluntary).

- Sessional group co-facilitator, 2.5 hours a week.

- Service manager, 28 hours a week.

- Counselling supervisor.

- 2019/20: 120 individuals supported with advice, counselling and group work.

- Most are supported through a combination of tailored and peer support. Some also opt for formal counselling.

- Over 10 years:

- stabilised: 3%

- lower dose: 50%

- withdrew completely: 29%

- no change: 6%

- not known or applicable: 11%.

- Patient experiences:

- “When I attended REST initially, I had lost just about all hope, was sick, confused, forgetful, angry and withdrawn. 6 months down the line I’ve got more hope, support, peace of mind and am slowly preparing to return to work on a part time basis. No one else provides what REST does, it is a service that should be more widely available.”

- “I have been totally free from benzodiazepines since 2017, many thanks to this group.”

- “REST staff understand the experience of benzodiazepine withdrawal in a way that can only be gained from years of listening. They know each of our stories in depth and how far each of us has come. This is invaluable to us.”

Factors for success

- Reactive peer community service model – approach is reactive, peer-led and community based, which allows the service to match the needs of individuals engaging with the service. The model is primarily psychosocial, rather than medical, which supports greater engagement and long-term behavioural changes.

- Integration with a larger organisation – integration with Change Grow Live has helped improve patient pathways, increase engagement with clinicians and broaden the range of services that individuals can access.

- Holistic approach – the service considers people holistically, supporting them in ways beyond tackling dependency, such as into volunteering and bolstering their aspirations. For example, one person found employment with the support of REST after being on 12 different psychoactive medications; others have begun volunteering after being told they would never be well enough to work.

- Flexible timescales – individuals can access the service for as long as they find it helpful (except for the number of sessions offered, which is set), even once they have withdrawn. This open timeframe also allows trust to be built up between the individual and the service, and those who have withdrawn to continue to be supported as needed to sustain their recovery.

- Involvement of those with lived experience – those with lived experience are at the centre of service design and many elements are co-produced or delivered by those with lived experience.

Case study 3: Pharmacy referral to liaison psychiatry service

Nottingham University Hospitals (NUH)

Psychotropic drug use in older patients is a significant concern as the inappropriate use of these drugs in those with frailty can increase the risk of adverse drug reactions, leading to harm events such as falls and fractures.

A multi-professional and multi-agency approach is required.

The service

A referral mechanism was established between the NUH clinical pharmacy team and the community liaison psychiatry team via ‘Rio’, the Mental Health Electronic Patient Record System.

Workforce

- Rapid response liaison psychiatry service in primary care.

- Clinical healthcare for older people (HCOP) team.

- Associated medical HCOP consultants – in both primary and secondary care.

Outcomes

Over 22 months the acute frailty pathway made 59 referrals (104 unique psychotropic medicines were reviewed). Following referral:

- 29% of prescribed psychotropic drugs were permanently deprescribed with appropriate safety netting

- 13% were reduced

- 31% remained the same

- the remaining medicines were increased or switched following review or stopped for purposes of an end of life treatment pathway.

Factors for success

- Multiprofessional and multi-agency approach to tackle the issue. Appropriate patients are identified and referred by skilled specialist frailty pharmacists to the community liaison psychiatry team.

- Referral volumes are low; therefore, implementation was not predicated on availability of funding.

Case study 4: Benzodiazepine, opiate, gabapentinoid and Z-drug deprescribing (Benzodiazepines and Opioids Withdrawal Service)

Camden and Islington NHS Foundation Trust

The Benzodiazepines and Opioids Withdrawal Service (BOWS) was piloted in 2017 in partnership with Camden and Islington Substance Misuse Service in response to concerns about the high prescribing rates for opiates and benzodiazepines locally. It has since been developed and expanded, reflecting the increasing awareness of the problems that can be associated with these medicines.

The service now offers advice, support and deprescribing for patients who are prescribed benzodiazepines, opiates, Z-drugs and gabapentinoids in primary care, and also supports GPs.

The service

BOWS clinics operate in 20 GP surgeries across Camden and Islington. Referrals come from GP surgeries, self-referrals, pain clinics and musculoskeletal (MSK) services. When there is no clinic in a surgery BOWS can assess, make recommendations regarding prescribing and work with patients remotely or from the Substance Misuse Service.

BOWS offers a range of services:

- Advice and information – about medications and deprescribing.

- Stabilising medication – some patients use medication erratically or use illicit drugs as well.. BOWS uses shared decision-making principles, keeping in regular contact and sometimes reducing the frequency of pick up to stabilise medication and reduce the risk.

- Gradual reduction – for most patients, a tapering of dose is a safer and more realistic option than immediate deprescription. This can also mean patients do not turn to illicit sources or a more harmful prescribed alternative.

- Nazareth method (developed by Professor Irwin Nazareth as part of the BOWS pilot):

- patients on a combination of benzodiazepines, Z-drugs, opiates and gabapentinoids are consulted about which medication they would like to reduce first.

- for opiates, a variety of approaches but BOWS recognises that a tapering dose, rather than complete cessation of the opiate, is a safer option.

- regular contact for support.

- Psychosocial support – patients can access a support group and resources and expertise at Camden and Islington Substance Misuse Service.

- CBT insomnia (CBTi) – offered on an individual basis and as group sessions for patients where insomnia is a significant problem.

- Liaising with pain clinic – BOWS ACT for pain group.

Workforce

- 1 WTE service manager

- 2 WTE senior nurse non-medical prescribers

- 2 WTE specialty doctor

Outcomes

Data collected between April 2019 and March 2020 shows:

- 205 patients from 24 different surgeries with the following primary medicine breakdown were assessed:

- 119 benzodiazepines (57%)

- 63 opioids (30%)

- 23 Z-drugs (11%).

- 103 patients (49%) started a dose reduction treatment plan in 2019.

- Of the patients who had started their dose reduction treatment plan before 2019, 106 (50%) completed this in 2019 and three in in 2020. Of these, 53 patients (26%) were completely deprescribed from the medicine and 53 (26%) had reduced their medicine doses.

Factors for success

- Being a commissioned service and supported by the commissioner.

- Engaging with local GP practices and other key local services.

- Using a patient-led approach to tapering and deprescribing.

- The service is run by experienced non-medical prescribers who are familiar with this cohort of patients.

- The service presents a varied offer to suit different patient needs: Nazareth method, CBTi, referrals to external services.

- Regular patient review and contact.

Case study 5: Alternatives to pharmacological interventions and appropriately commissioned services

Medicines Management Team, NHS South Yorkshire Integrated Care Board

Antidepressant prescribing rates have increased year on year, pre and post covid-19 pandemic, with NHS South Yorkshire Integrated Care Board (ICB) sub-ICB locality (ICBL) Rotherham among the highest nationally. A pilot programme was initiated to support deprescribing of long-term antidepressants in Primary Care, where clinically appropriate, and to refer patients to NHS Talking Therapies for Anxiety and Depression and social prescribing to provide alternatives to medication. A stand-alone “One-Stop Review Clinic” was set-up to review, and prescribe titration regimes, for patients using their own registered GPs Practice record.

Patients were offered and referred to local interventions where appropriate, such as social prescribing,and NHS Talking Therapies for Anxiety and Depression and local voluntary services.. A sub-ICBLbased medicines management team pharmacist led the pilot, with the support of a Band 8a pharmacist and administrative support, building on a multidisciplinary approach involving other healthcare professionals and providers.

The most suitable interventions and options available were openly and honestly discussed with patients throughout their journey.

Workforce

- 0.2 x WTE Band 8b Clinical Lead Pharmacist

- 0.8 x WTE Band 8a Independent Prescribing Pharmacist

- 1 x WTE Band 4 admin support

- Additional support from other already commissioned services ( Social prescribing, and NHS Talking Therapies for Anxiety and Depression)

Outcomes

Audit measures include the number of patients who:

- are on antidepressants for more than two years (without history of repeat depressive episodes or relapse) = 8446

- self-referred to service = 692

- eligible to be reviewed = 657 reduce antidepressant dose = 252 (38%, 252/657)

- stop taking antidepressants = 405 (62%, 405/657)

Critical success factors

- Multidisciplinary approach.

- Use of clinical GP systems reporting data to identify trends and eligible patient groups.

- Recording (and prescribing) directly in patient’s GP record. Avoids additional workload to the GP Practice and any changes are recorded, and visible, immediately in patient record.

- Virtual consultations (telephone or video) to allow the service to be flexible in meeting patient need; this also meant provision was not interrupted by COVID-19.

- Shared decision-making with the patient deciding their end-point (reduced dose or stopping).

- Open and transparent conversations with patient throughout journey.

- Ensuring patients are clearly informed at every step and follow-ups timed to their individual needs

- Patient having the same named Clinician supporting them throughout their deprescribing journey.

- The pilot clinic successfully stopped or reduced dose of antidepressants in 657 patients, with only a small number (8) reporting adverse effects, without creating any additional workload for member GP Practices.

Case study 6: Living Well with Pain Programme

NHS Gloucestershire

Gloucestershire integrated care board (ICB) is bringing together people to collectively provide high value, co-produced, integrated, evidence-based support and services to achieve the best quality of life for people with chronic pain. A Pain Programme Group includes stakeholders from primary and secondary care, people with chronic pain, VCSE colleagues, mental health commissioners and providers, adult social care, charitable bodies and ICB partners leading on health inequalities, self-management and healthy communities, personalisation, social prescribing and creative health, transformation programme leaders, and patient engagement and experience teams.

The programme also benefits from a commissioned clinical lead who provides clinical oversight and leadership. The Living Well with Pain Programme (LWwPP) follows the clinical programme approach, which is integral to Gloucestershire’s ICS.

The service

The LWwPP is wide ranging and encompasses a range of programmes across Gloucestershire. Initiatives have included interactive education sessions for GPs, pharmacists, physiotherapists, and social prescribers about challenges in supporting people to live well with pain; a countywide initiative to support people in reducing pain medicines that are harmful; a highly successful online exercise offer for people with chronic pain; and health-coaching training for staff working with people with chronic pain.

This case study details the experience of offering a non-medical arts-based self-management option to adults living with persistent pain, to improve quality of life and increase opportunities for self-management of persistent pain and associated physical, psychological and social impact.

Art on Prescription is a form of social prescription and is a non-clinical intervention delivered by art practitioners for therapeutic benefit. It can be offered to people with a wide range of needs at a mild–moderate level of acuity and differs from art psychotherapy which may only be delivered by Health and Care Professions Council registered art therapists.

Artlift delivers the programme of 12 small group sessions to people identified by pain clinicians in the Pain Service at Gloucestershire Hospitals Foundation Trust. They have a personalised ‘What Matters To You’ conversation prior to the start of the programme and agree a personalised support plan and goals with each participant.

Sessions include arts activities and the bringing/sharing of food (adapted to online/telephone support through COVID-19 lockdown). Art forms are mixed media and may include elements of textiles, felting, printmaking, painting, drawing, water colours, filmmaking and sound recording.

Workforce

The programme was developed and implemented in collaboration with participants with lived experience, pain clinicians, commissioners and artists from Artlift (the delivery organisation).

Outcomes

- “It helped my pain as it makes me relax.”

- “It’s a distraction from the pain and a valuable service for people like me that suffer ongoing pain and mental health issues.”

- “I enjoyed meeting people in the same position as me and learning from each other, both artistically and from a pain management perspective.”

- “I’ve bought paints, sketchbooks and needle felting equipment which has made a massive difference to how I manage my pain at home.”

83% of participants showed a statistically significant improvement on the Warwick Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing Scale (WEMWBS).

Factors for success

- Listening/validating the pain experience.

- Co-development with patient of a personalised support plan with clear, agreed goals.

- Addressing mental health and abuse.

- Signposting to other resources.

- The opportunity for Artlift to strengthen relationships with the pain management clinic team aided the co-production of the programme and increased referral numbers.

- The ability to draw on the lived experience of those with persistent pain to shape the programme.

Delivery of the programme by artist facilitators with lived experience of persistent pain was very important as participants felt it was “vital” that artists had “empathy” around the condition and that trust was established.

Case study 7: Patient safety card

Opioids Community Pharmacy, Company Chemists’ Association (CCA)

The CCA’s seven members own about 6,000 pharmacies in the UK, representing almost half the market. The misuse of over the counter (OTC) opioids is a growing concern for community pharmacies.

The service

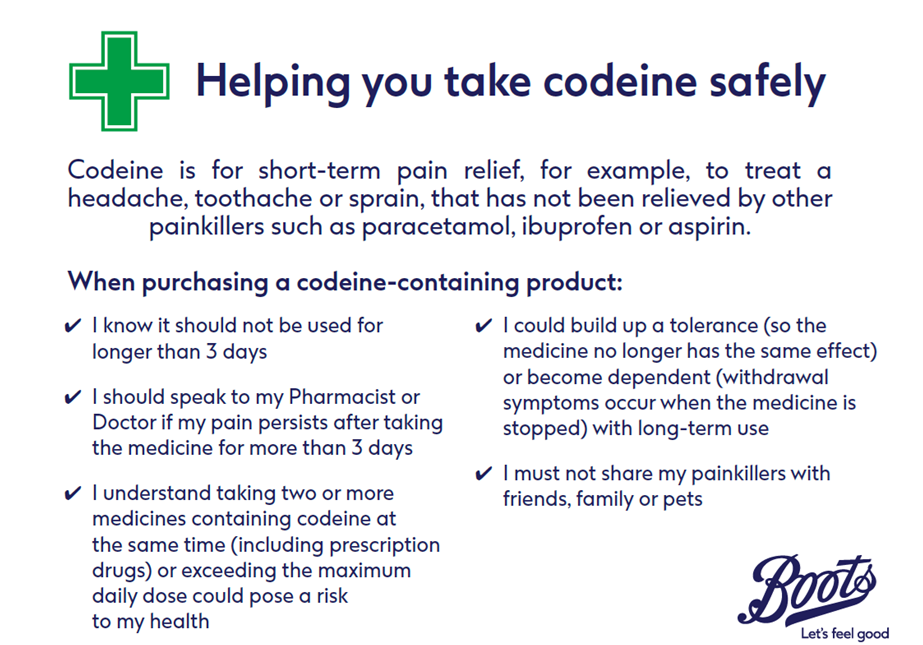

This scheme is a Boots® only initiative.

An education patient safety card was developed by a panel of community pharmacists and external experts, and piloted to identify its effectiveness in influencing safe and appropriate use of OTC codeine.

Information on recorded interactions for people requesting OTC codeine at community pharmacies was analysed along with responses to a web-based pharmacy staff survey. 24 Boots pharmacies submitted 3,993 interactions using the patient safety card.

Following successful pilot work, the patient safety card has been introduced in all Boots pharmacies as a conversational tool to help reinforce key advisory points pertaining to safe and appropriate use, to raise awareness of the potential risks from long-term opioid use and to disrupt patient behaviour patterns indicative of opioid abuse at the earliest opportunity.

Recognising that conversations with patients about opioid misuse or abuse may sometimes be challenging, the patient safety card helps pharmacy professionals to engage in dialogue with patients and, if appropriate, effect a compassionate approach to their signposting to suitable sources of support with any issues associated with opioid misuse.

Workforce

Community pharmacists.

Outcomes

- The findings of the pilot supported use of the patient safety card as a visual educational intervention to encourage appropriate use of OTC codeine in community pharmacies.

- Pharmacy staff rated most interactions ‘very easy’ or ‘easy’ in the survey.

- Customers known to pharmacy staff as frequent purchasers of OTC codeine were more likely not to purchase a pain relief medicine following interaction compared to those not known to staff.

Factors for success

Community pharmacists’ relationship with frequent purchasers of OTC codeine.

Footnote 1: These medicines are often prescribed for multiple indications. More information can be found in the British National Formulary or the summaries of product characteristics.

Footnote 2: Up-to-date data from the English Dispensing Dataset (EPD) can be viewed on the Opioid prescribing comparators dashboard (NHS BSA).