June 2023

Foreword

The founding of the NHS 75 years ago was a huge milestone in our national history. It was born out of hope, and for millions of people it represented the chance of a healthier future for them and their families. But as a new national service it faced real challenges. Chief among them was building a workforce capable of meeting the needs of a population suffering the effects of war, poverty and diseases as yet untamed by science, including tuberculosis.

Fast forward to 2023: the NHS in England now has many times the number of staff, including doctors, nurses, therapists and scientists, and is therefore capable of delivering a far greater volume and breadth of care. But, at the same time, local services report vacancies totalling over 112,000. This is a reflection of how the needs of our population have grown and changed, thanks in large part to the role better care and advances in medicine have played in increasing life-expectancy by 13 years since 1948.

That change will continue; the number of people aged over 85 is estimated to grow 55% by 2037, as part of a continuing trend of population growth which outstrips comparable countries. Inaction in the face of demographic change is forecast to leave us with a shortfall of between 260,000 and 360,000 staff by 2036/37. The lack of a sufficient workforce, in number and mix of skills, is already impacting patient experience, service capacity and productivity, and constrains our ability to transform the way we look after our patients. A growing shortfall would mean growing challenges and lost opportunities.

If the NHS is to continue to be the health service the public overwhelmingly wants and is proud of – one which provides high quality care for patients, free at the point of need – it needs a robust and effective plan to ensure we have the right number of people, with the right skills and support in place to be able to deliver the kind of care people need.

The publication of our NHS Long Term Workforce Plan is therefore one of the most seminal moments in our 75-year history. This is the first time the government has asked the NHS to come up with a comprehensive workforce plan; a once-in-a-generation opportunity to put staffing on a sustainable footing and improve patient care.

We have grasped that opportunity. Our Plan is ambitious, and it is bold, while being rooted in the reality experienced by patients and staff now, and it is rigorously aligned to the improvements in care that we aspire to make for patients. Even more crucially, it doesn’t just herald the start of the biggest recruitment drive in health service history, but also of an ongoing programme of strategic workforce planning – something which is unique amongst other health care systems with national scale.

In the pages that follow, we set out a strategic direction for the long term, as well as concrete and pragmatic action to be taken locally, regionally and nationally in the short to medium term to address current workforce challenges. Those actions fall into three clear priority areas:

- Train: significantly increasing education and training to record levels, as well as increasing apprenticeships and alternative routes into professional roles, to deliver more doctors and dentists, more nurses and midwives, and more of other professional groups, including new roles designed to better meet the changing needs of patients and support the ongoing transformation of care.

- Retain: ensuring that we keep more of the staff we have within the health service by better supporting people throughout their careers, boosting the flexibilities we offer our staff to work in ways that suit them and work for patients, and continuing to improve the culture and leadership across NHS organisations.

- Reform: improving productivity by working and training in different ways, building broader teams with flexible skills, changing education and training to deliver more staff in roles and services where they are needed most, and ensuring staff have the right skills to take advantage of new technology that frees up clinicians’ time to care, increases flexibility in deployment, and provides the care patients need more effectively and efficiently.

Taking these actions will allow the NHS to make sustainable progress on our core priorities for patients, such as improving access to primary and community care, providing safe and timely urgent and emergency care, and continuing to reduce the COVID-19 backlog for elective care. And we welcome the government’s commitment to the Plan and investment to provide the additional education and training places we need over the next five years.

Developing a workforce plan that stands the test of time is a hard thing to do in any sector, and particularly so in the NHS. The evidence from our history tells us that the pace of technological and scientific progress means we cannot predict with certainty how the workforce needs of the NHS will look in 15 years’ time. The pressures of the present – felt by patients and staff alike – can also make the needs of the future feel less important.

But we can set a direction of travel, and commit – as we are – to this being the start of an ongoing process to refresh the Plan and ensure it is aligned with wider service planning. The coming together of NHS England, Health Education England and NHS Digital into a new, single organisation means we are now much better equipped to undertake this task, and therefore to ensure the health service is geared up to meet the evolving challenges – and take the emerging opportunities – that the next 15 years hold.

The strategy and actions set out in this Plan have been developed by the NHS, but done so in close partnership with staff groups and wider experts, with the support of the government. The number of organisations and individuals who deserve thanks for their contribution stretches into the hundreds. This Plan belongs to all of us.

As we now embark on the equally important job of delivering on its contents, and to the ongoing review and development needed to ensure it remains relevant to the changing needs of the people we serve, it will continue to take all of us to achieve success – an ambitious, sustainable and resilient NHS, there for patients now and for future generations.

Amanda Pritchard, NHS Chief Executive

Overview

We will ensure the NHS has the workforce it needs for the future.

Train – Grow the workforce

By significantly expanding domestic education, training and recruitment, we will have more healthcare professionals working in the NHS. This will include more doctors and nurses alongside an expansion in a range of other professions, including more staff working in new roles. This Plan sets out the path to:

- Double the number of medical school training places, taking the total number of places up to 15,000 a year by 2031/32, with more medical school places in areas with the greatest shortages, to level up training and help address geographical inequity. To support this ambition, we will increase the number of medical school places by a third, to 10,000 a year by 2028/29. The first new medical school places will be available from September 2025.

- Increase the number of GP training places by 50% to 6,000 by 2031/32. We will work towards this ambition by increasing the number of GP specialty training places to 5,000 a year by 2027/28. The first 500 new places will be available from September 2025.

- Increase adult nursing training places by 92%, taking the total number of places to nearly 38,000 by 2031/32. To support this ambition, we will increase training places to nearly 28,000 in 2028/29. This forms part of our ambition to increase the number of nursing and midwifery training places to around 58,000 by 2031/32. We will work towards achieving this by increasing places to over 44,000 by 2028/29, with 20% of registered nurses qualifying through apprenticeship routes compared to just 9% now.

- Provide 22% of all training for clinical staff through apprenticeship routes by 2031/32, up from just 7% today. To support this ambition, we will reach 16% by 2028/29. This will ensure we train enough staff in the right roles. Apprenticeships will help widen access to opportunities for people from all backgrounds and in underserved areas to join the NHS.

- Introduce medical degree apprenticeships, with pilots running in 2024/25, so that by 2031/32, 2,000 medical students will train via this route. We will work towards this ambition by growing medical degree apprenticeships to more than 850 by 2028/29.

- Expand dentistry training places by 40% so that there are over 1,100 places by 2031/32. To support this ambition, we will expand places by 24% by 2028/29, taking the overall number that year to 1,000 places.

- Train more NHS staff domestically. This will mean that we can reduce reliance on international recruitment and agency staff. In 15 years’ time, we expect around 9– 10.5% of our workforce to be recruited from overseas, compared to nearly a quarter now.

Retain – Embed the right culture and improve retention

By improving culture, leadership and wellbeing, we will ensure up to 130,000 fewer staff leave the NHS over the next 15 years. We will:

- Continue to build on what we know works and implement the actions from the NHS People Plan to ensure the NHS People Promise becomes a reality for all staff by rolling out the interventions that have proven to be successful already. For example, ensuring staff can work flexibly, have access to health and wellbeing support, and work in a team that is well led.

- Implement plans to improve flexible opportunities for prospective retirees and deliver the actions needed to modernise the NHS Pension Scheme, building on changes announced by the government in the Spring Budget 2023 to pension tax arrangements, which came into effect in April 2023.

- From autumn, recently retired consultant doctors will have a new option to offer their availability to trusts across England, to support delivery of outpatient care, through the NHS Emeritus Doctor Scheme.

- Commit to ongoing national funding for continuing professional development for nurses, midwives and allied health professionals, so NHS staff are supported to meet their full potential.

- Support the health and wellbeing of the NHS workforce and, working with local leaders, ensure integrated occupational health and wellbeing services are in place for all staff.

- Explore measures with the government such as a tie-in period to encourage dentists to spend a minimum proportion of their time delivering NHS care in the years following graduation.

- Support NHS staff to make use of the change announced in the Spring Budget 2023 that extended childcare support to working parents over the next three years, to help staff to stay in work.

Reform – Working and training differently

Working differently means enabling innovative ways of working with new roles as part of multidisciplinary teams so that staff can spend more time with patients. It changes how services are delivered, including by harnessing digital and technological innovations. Training will be reformed to support education expansion. We will:

- Focus on expanding enhanced, advanced and associate roles to offer modernised careers, with a stronger emphasis on the generalist and core skills needed to care for patients with multimorbidity, frailty or mental health needs.

- This includes setting out the path to grow the proportion of staff in these newer roles from around 1% to 5% by the end of the Plan by:

- Ensuring that more than 6,300 clinicians start advanced practice pathways each year by 2031/32. We will support this ambition by having at least 3,000 clinicians start on advanced practice pathways in both 2023/24 and 2024/25, with this increasing to 5,000 by 2028/29.

- Increasing training places for nursing associates (NAs) to 10,500 by 2031/32. We will work towards this by training 5,000 NAs in both 2023/24 and 2024/25, increasing to 7,000 a year by 2028/29. By 2036/37, there will be over 64,000 nursing associates working in the NHS, compared to 4,600 today.

- Increasing physician associate (PA) training places to over 1,500 by 2031/32. In support of this, around 1,300 physician associates (PAs) will be trained per year from 2023/24, increasing to over 1,400 a year in 2027/28 and 2028/29, establishing a workforce of 10,000 PAs by 2036/37.

- Grow the number and proportion of NHS staff working in mental health, primary and community care to enable the service ambition to deliver more preventative and proactive care across the NHS. This Plan sets out an ambition to grow these roles 73% by 2036/37.

- Work with professions to embrace technological innovations, such as artificial intelligence and robotic assisted surgery. NHS England will convene an expert group to identify advanced technology that can be used most effectively in the NHS, building on the findings of the Topol Review.

- Expand existing programmes to demonstrate the benefits of generalist approaches to education and training and ensure that, at core stages of their training, doctors have access to development that broadens their generalist and core skills.

- Work with partners to ensure new roles are appropriately regulated to ensure they can use their full scope of practice, and are freeing up the time of other clinicians as much as possible – for example, by bringing anaesthesia and physician associates in scope of General Medical Council (GMC) registration by the end of 2024 with the potential to give them prescribing rights in the future.

- Support experienced doctors to work in general practice under the supervision of a fully qualified GP. We will also ensure that all foundation doctors can have at least one four-month placement in general practice, with full coverage by 2030/31.

- Work with regulators and others to take advantage of EU exit freedoms and capitalise on technological innovation to explore how nursing and medical students can gain the skills, knowledge and experience they need to practise safely and competently in the NHS in less time. Doctors and nurses would still have to meet the high standards and outcomes defined by their regulator.

- Support medical schools to move from five or six-year degree programmes to four- year degree programmes that meet the same established standards set by the GMC, and pilot a medical internship programme which will shorten undergraduate training time, to bring people into the workforce more efficiently so that in future students undertaking shorter medical degrees make up a substantial proportion of the overall number of medical students.

- The Plan is based on an ambitious labour productivity assumption of up to 2% (at a range of 1.5–2%). This ambition requires continued effort to achieve operational excellence, reducing the administrative burden through technological advancement and better infrastructure, care delivered in more efficient and appropriate settings (closer to home and avoiding costly admissions), and using a broader range of skilled professionals, upskilling and retaining our staff. These opportunities to boost labour productivity will require continued and sustained investment in the NHS infrastructure, a significant increase in funding for technology and innovation, and delivery of the broader proposals in this Plan.

Summary

- Hard-working staff are the bedrock of the NHS.

- However, for decades, the NHS workforce has not been planned in a co-ordinated way. This has limited our ability to best use the skills of NHS staff, the ability to set out forecasts of future need and then act on them, and being able to properly link workforce, service and financial planning to fully maximise return on investment.

- This has been a major challenge in the NHS since its inception. These challenges have combined with the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, imposing new demands on services and pressures on staff that are unprecedented in the NHS’s history.

- The NHS was therefore commissioned by the government to produce an NHS Long Term Workforce Plan setting out future demand and supply requirements, and the actions and reforms needed to support the overall strategy for the NHS.

- This Plan sets out modelling of NHS workforce demand and supply over a 15-year period and the resulting shortfall. It details the actions that will be taken in the coming years to address the identified shortfall in addition to, and building on, actions and investment already committed over the next two years.

- It shows that, without concerted and immediate action, the NHS will face a workforce gap of more than 260,000–360,000 staff by 2036/37.

- We set out, for the first time and in the NHS’s 75th year, a comprehensive plan to close this shortfall and address the changing needs of patients over the next 15 years. It is a plan for investment and a plan for change: to train more staff, retain our dedicated workforce and reform the way we work.

- This Plan expands on the previous work and recommendations that set the direction for the NHS workforce [see references 1, 2 and 3]. In addition, it relies on valuable perspectives from over 100 stakeholders across more than 60 organisations (Annex A).

- It is the first step in a new iterative approach to NHS workforce planning. We will regularly update the model to inform operational and strategic planning, in light of changing circumstances. We will now work with NHS staff, NHS employers, clinical leaders, royal colleges, professional regulators, as well as integrated care boards (ICBs) and integrated care systems (ICSs) and others, to implement and build on the actions and ambitions set out.

The case for change

- The number of NHS staff has grown materially in the past decade. Since 2010, NHS staffing has increased by 263,000 full-time equivalent (FTE) staff, [see references 4, 5 and 6] including 42,000 more doctors and 55,000 more nurses, health visitors and midwives, with an estimated increase of 4,600 doctors and 2,400 nurses in general practice. However, healthcare need has also been growing significantly, driven by ageing and increasing morbidity, and outstripping the growth in workforce FTEs. We know the NHS is facing clear and pressing workforce challenges.

- Rising demographic pressures and a changing burden of disease are increasing demand for NHS services. Over the next 15 years, the population of England is projected to increase by 4.2%, but the number of people aged over 85 will grow by 55% [see reference 7]. Patients’ needs are changing with increasing levels of multimorbidity and frailty leading to increasing complexity of service delivery. By 2037, unless more is done to moderate current trends, two-thirds of those over 65 will have multiple health conditions and a third of those people will also have mental health needs.

- Historically, while the education and training pipeline has increased and the workforce has grown by 25% since 2010, [see reference 8] the number of staff trained has not kept pace with demand for NHS services. To fill service gaps and ensure safe staffing levels, the NHS is firmly reliant on temporary staffing and international recruitment [see reference 9]. Of the doctors who joined the UK workforce in 2021, 50% were international medical graduates [see reference 10]. And, in 2022/23, about half of new nursing registrants in England were trained overseas [see reference 11]. This leaves the NHS exposed to high marginal labour costs and risks the sustainability of services in the longer term given the growing global demand for skilled healthcare staff.

- The need for our workforce to grow and evolve is evidenced by the fact that there were over 112,000 vacancies across the NHS workforce in March 2023 [see reference 12]. Compared to other OECD countries, the UK sits below the average for numbers of nurses and medics per size of population.

- These are challenges faced by other countries across the developed world. In England, staffing shortages limit the capacity of the NHS to deliver the quantity and quality of services that people expect, impact on staff wellbeing, and hinder the NHS’s ability to reform and provide value-for-money for taxpayers.

- The current NHS workforce largely concentrates on responding to care and health needs, rather than doing more to fulfil the role it can play in preventing ill health. Likewise, we will need to continue the shift over the coming years away from episodic care, towards a newer paradigm of ongoing, chronic care to support the increasing number of people with multimorbidity, frailty and complex needs. New and emerging roles, including advanced practice, are growing but not at a sufficient rate to fundamentally alter the overall shape of the workforce. There is a growing professional consensus that meeting the needs of patients, and changing population demands, will require a more flexible workforce with more generalist and core skills, alongside specialist skills.

- The NHS Long Term Plan [see reference 13] described the changes needed for an NHS fit for the 21st century, including boosting primary and community care, investing in mental healthcare, diagnosing cancer earlier, and focusing on population health, integration and prevention. We are seeking to achieve these changes throughout the NHS in a way that learns from and builds on the experience of the COVID-19 pandemic (for example, the rapid roll out of telemedicine systems across primary care), recognising the long-lasting impact on the NHS. Scaling of NHS care delivered in the community requires rapid expansion of the necessary workforce and the development of more flexible and integrated teams.

- NHS staff, learners and volunteers do not always have an equally good experience of work in the NHS. The NHS workforce is the most diverse it has ever been; for example, nearly 25% of staff come from an ethnic minority background [see reference 14]. We want everyone working in the NHS to have a positive experience, but we recognise this is not always the case.

- Developments in science, research, technology, digital and data will continue. Genomics and artificial intelligence (AI) in particular will transform our ability to prevent, diagnose, treat and manage disease, supporting a shift towards better prevention of disease and more personalised care outside hospital. Harnessing these opportunities requires NHS staff to continue to build digital skills and capabilities and will change ways of working, releasing staff time to focus on patient care. With strong local leadership and management, combined with enabling technology, the use of more diverse roles will change the skills required to meet patient needs and will expand the capacity of community services to deliver this type of care.

- Given the unique challenges facing the NHS workforce and the length of time it takes to train new clinical staff (particularly new consultants and GPs), a comprehensive and long-term approach to workforce planning is required.

Putting the workforce on a sustainable footing for the long term

- Over the course of the Plan, concerted action will need to continue, supported by increased investment to expand education and training, as well as increasing recruitment from the wider labour market. Action will need to be sustained across improving culture and retention, training the workforce differently, evolving the skills mix and delivering productivity. The Plan assumes an ambitious labour productivity assumption of 1.5–2%. This ambition requires a combination of delivering care closer to home while avoiding costly admissions, achieving operational excellence, reducing administrative burden through better technology and infrastructure, and capturing the benefits appropriately in productivity measurement. The productivity ambition will require continued and sustained investment in the NHS infrastructure, a significant increase in funding for technology and innovation, and the delivery of the broader proposals in this Plan.

- The ongoing speed and scale of action in each area will determine how quickly workforce shortfalls can be closed, services can be reshaped and the NHS’s dependence on international recruits and temporary staffing can be scaled back.

- The modelling used throughout the Plan provides a set of broad ranges to quantify the potential impact of actions over its 15-year timeframe. The suggested impact is inevitably subject to a degree of uncertainty.

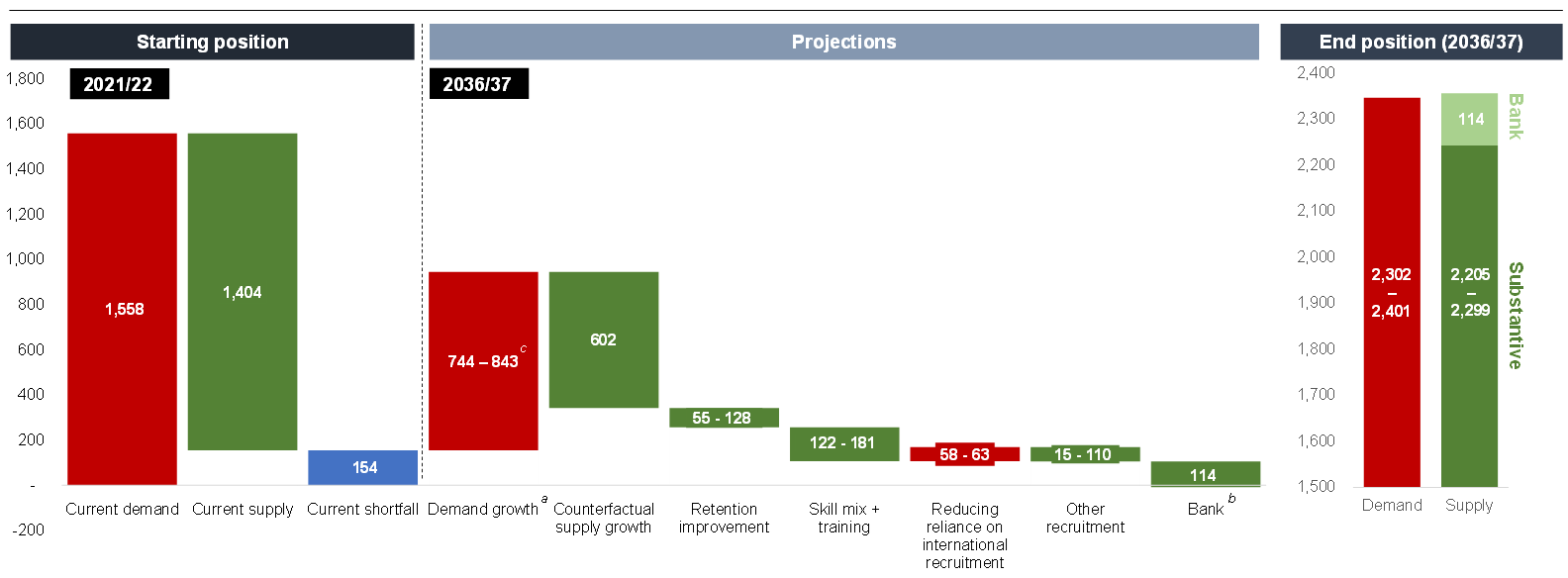

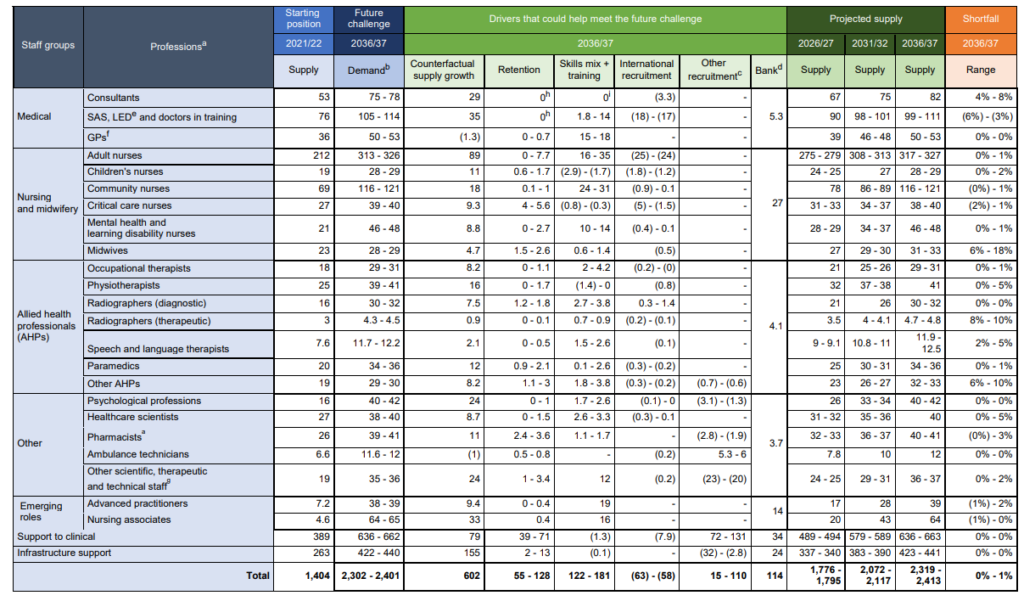

Figure 1: Drivers of NHS workforce demand and supply in 2021/22 and as projected for 2036/37, FTEs 000s

a) Demand growth is net growth, once taking into account workforce required to improve performance, service and pathway reforms to deliver care in the most appropriate setting, mitigating demand growth through prevention and proactive care, and productivity improvement.

b) This assumes that the proportion of NHS staff who choose to work solely on bank contracts will stay the same.

c) Ranges are driven by different assumptions used in the modelling to reflect uncertainty in key factors, including productivity (which impacts on demand), retention, training, and the estimated levels of education and international recruitment required to reduce staff shortfalls, and the broader recruitment required to meet demand. These are further set out in Annex B.

- The modelling estimates that the starting shortfall between demand and supply for NHS staff is approximately 150,000 full-time equivalents (FTEs), a gap that is filled with temporary staffing. Before any of the interventions set out in this Plan, and even after factoring in ambitious expectations for improved productivity, the workforce shortfall across NHS organisations will grow to 260,000–360,000 FTEs by 2036/37. Most professions will see shortfalls grow, but this trend will be more pronounced for some professions.

- The shortfall in qualified GPs is projected to be 15,000 FTEs by 2036/37. The model assumes a boost in doctors in GP specialty training and newly qualified GPs from interventions in recent years, but more will be needed to keep up with expected demand.

- By 2036/37 the FTE shortfall in community nurses will be at least 37,000; it was 6,500 in 2021/22. The mental health nursing and learning disability nursing shortfall will grow to more than 17,000 FTEs, while that for critical care nurses will remain at around 4,000 FTEs.

- Among the allied health professions (AHP), shortfalls will increase the most for paramedics, occupational therapists, diagnostic radiographers, podiatrists, and speech and language therapists.

- Within the non-registered workforce, healthcare support workers are anticipated to have the largest shortfall.

Longer term assessment of actions needed to support change

- Even with the highest projected impact of retention and productivity, there will be a workforce shortfall and significant reliance on international recruitment at the end of 2036/37 under current trends without further investment in education and training. We will therefore need to grow our workforce; our long-term assessment is that domestic education and training needs to expand by around 50% to 65% over the next 15 years.

- To meet the growth needed in the future, NHS organisations will need to do more to recruit staff from the wider labour market, particularly into direct entry and support worker roles. The Plan estimates that more than 204,000 new support workers will be required to meet demand over the next 15 years. The detailed actions to grow the workforce are set out in Chapter 2.

- The collective impact of proposed actions to embed the right culture and improve retention, aligned to increases in capacity, would help reduce the number of NHS leavers by between 55,000 and 128,000 FTEs over the 15-year timeframe. Chapter 3 sets out the detail of what systems, NHS England and our partners will need to focus on to make this a reality over the longer term.

- Increasing capacity and working differently is anticipated to reduce projected shortfalls and improve labour productivity. Chapter 4 sets out the case for taking full advantage of digital and technological innovations, such as speech recognition, robotic process automation, remote monitoring and AI. Building on the Topol Review, [see reference 15] NHS England and government, will convene an expert group to ensure the NHS takes advantage of the opportunities that AI can offer. Chapter 4 also outlines the training reforms needed to support the expansion set out in the Plan and discusses the need for NHS workforce plans to offer modernised careers, with a stronger focus on the generalist and core skills needed to care for patients with multimorbidity, frailty or mental health needs.

- With the combined impact of interventions on productivity improvement, retention, recruitment, the adoption of new roles, training and education, the shortfall is expected to fall over the modelled period. It is anticipated that, while shortfalls persist, they will continue to be largely covered by use of temporary staffing, including a mixture of bank and agency. The position for individual professions varies.

Education and training expansion

- As a first and significant step, this Plan commits to a new suite of actions over the next six years to support and develop the NHS workforce with an immediate boost in training numbers.

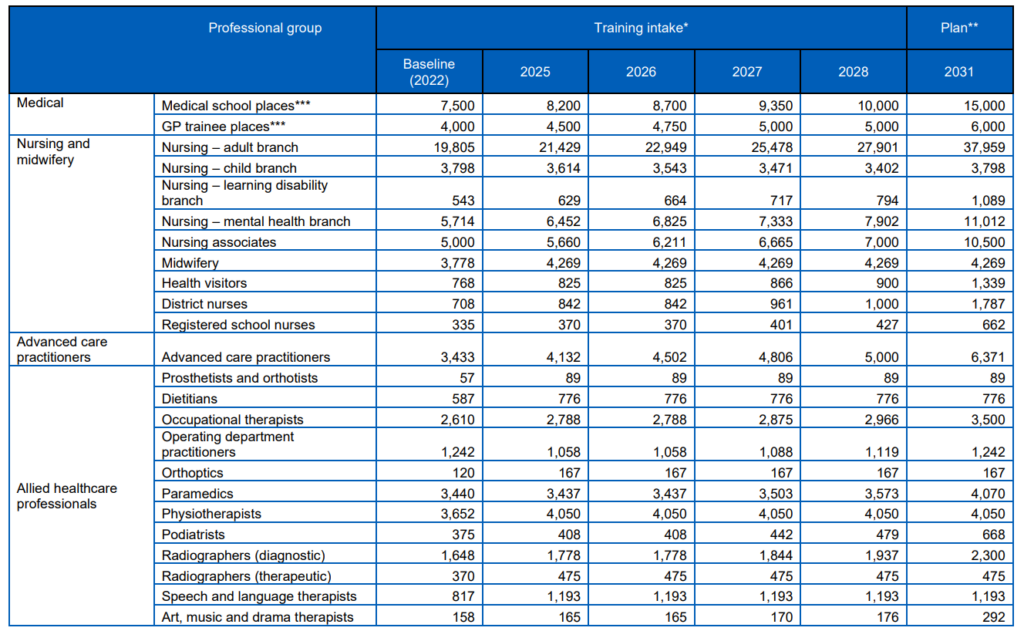

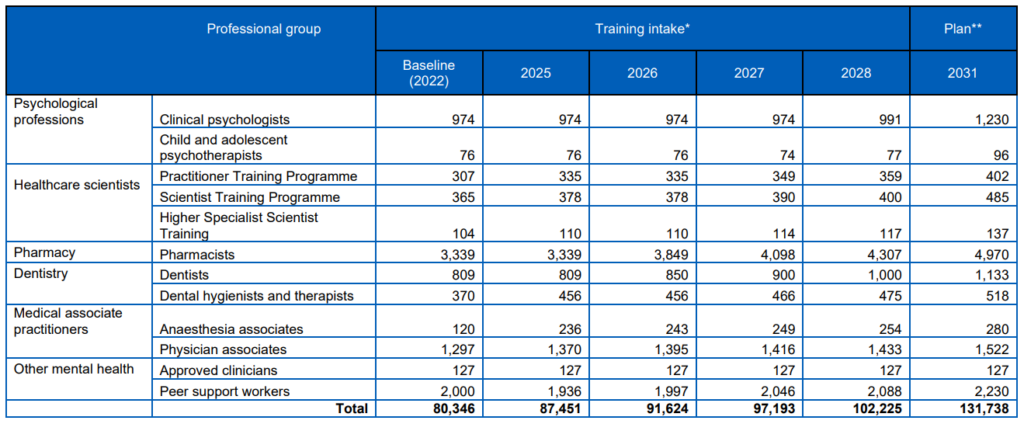

- The government will invest more than £2.4 billion to fund the 27% expansion in training places by 2028/29. This will enable more than half a million trainees to begin clinical training over the next six years, an addition of nearly 60,000 compared to maintaining current training levels. This is a significant first step on the path to increasing education and training by 64% by 2031/32. As part of this ambition, we aim to:

- Double the number of medical school places, taking the total number of places to 15,000 by 2031/32. We will work towards this expansion by increasing medical school places by a third, to 10,000 by 2028/29. We will also ensure there is adequate growth in foundation placement capacity, as those taking up these new places begin to graduate, and a commensurate increase in specialty training places that meets the demands of the NHS in the future. We will work with stakeholders to ensure this growth is sustainable and focused in the service areas where need is greatest.

- Increase the number of GP specialty training places by 50% to 6,000 by 2031/32. To support this ambition, GP specialty training places will initially grow by 500 places by 2025/26, increasing to 1,000 additional places (5,000 overall) by 2027/28.

- Increase adult nursing training places by 92%, taking the total number of places to nearly 38,000 by 2031/32. We will work towards this ambition by increasing adult nursing training places over the next six years so that, in 2028/29, at least 8,000 more adult nurses will start training compared to current levels. Over this same time period, to 2028/29, training places will increase by 38% for mental health nursing and 46% for learning disability nursing. By 2028/29, there will be a total of 40,000 nursing places funded. This will put us on the path to increase nursing training places by 80% to over 53,500 by 2031/32.

- Increase training places for nursing associates (NAs) to 10,500 by 2031/32. In support of this, over the coming six years, we will increase training places by 40% to 7,000 by 2028/29.

- Increase AHP training places to 17,000 by 2028/29, putting us on the path to increasing places overall by a quarter to more than 18,800 by 2031/32.

- Increase training places by 26% for both clinical psychology and child and adolescent psychotherapy by 2031, taking the combined number of training places to over 1,300. Training places will be more than 1,000 each year up to 2028/29.

- Expand training places for pharmacists by 29% to around 4,300 by 2028/29. This will put us on the path to increasing training places by around half overall to almost 5,000 by 2031/32. The number of pharmacy technicians will also grow in future years.

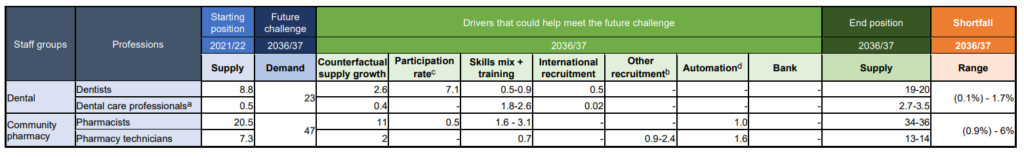

- Increase training places for dental therapists and hygiene professionals to more than 500 by 2031/32, and increase training places for dentists by 40% to more than 1,100 by this same year. In support of this, we will increase training places for dental therapy and hygiene professionals by 28% by 2028/29, with an increase of 24% for dentists to 1,000 places over the same period.

- Increase training places for healthcare scientists by 13% to more than 850 places by 2028/29, putting us on the path to increase training places by more than 30% to over 1,000 places by 2031/32.

- Expand advanced practice training by 46%, so that 5,000 clinicians are starting advanced practice pathways each year. This puts us on the path to increasing training places so that more than 6,300 clinicians start advanced practice pathways each year by 2031/32.

- Provide 16% of clinical training places as apprenticeships by 2028/29 compared to 7% now. This will offer greater access to training opportunities for local communities and put us on the path to offering 22% of clinical training places through apprenticeship routes by 2031/32.

- These actions build on the steps that NHS England is already taking to grow and train the NHS workforce. Investment in education and training is planned to increase from £5.5 billion to £6.1 billion over the next two years, and actions are underway to:

- Train 5,000 nursing associates (NAs) and around 1,300 physician associates (PAs) in 2023/24 and 2024/25. This Plan emphasises the need to target more PA roles towards primary care and mental health services.

- Ensure at least 3,000 clinicians start advanced practice pathways in both 2023/24 and 2024/25, tailored to support service demand.

- Continue funding the shortened midwifery course for registered nurses in 2023/24 and 2024/25.

- Complete the planned increase in medical specialty training places by September 2024 to more than 2,000 over three years, as well as 1,000 additional specialty training places focusing on areas with the greatest shortages. This expansion is both supporting existing planned growth for mental health, cancer and diagnostic services, as well as elective recovery, urgent and acute care, maternity services and public health medicine.

- These actions are on top of progress already made over recent years including:

- Growth in medical training places since 2018 – a 25% increase from 6,000 to 7,500.

- Growth in GP specialty training places (with over 4,000 doctors accepting GP specialty training places in 2022, compared to 2,671 in 2014), which is beginning to increase frontline capacity.

- Investment in additional direct patient care staff in primary care, with over 29,000 FTE staff in post now compared to March 2019 [see reference 16].

- Progress towards growing the permanent nursing workforce by 50,000 with over 44,000 more nurses working in the NHS in March 2023, compared to September 2019, [see references 17, 18].

- A 13% planned increase in the number of midwives in training by 2024/25, compared to 2021/22.

- Substantial changes by the government in the Spring Budget 2023 [see reference 19] to pension tax arrangements (from April 2023), which ensures that experienced clinicians are not pushed out of the workforce for tax reasons and alleviates disincentives for taking on additional work or responsibilities.

- The extension in the Spring Budget 2023 [see reference 20] of childcare support to working parents over the next three years, which will support NHS staff to stay in work and increase participation rates (the proportion of a full-time role individual staff members can fulfil).

Impact of the NHS Long Term Workforce Plan

- Implementing this Plan will have a significant impact on the NHS workforce of the future, and the delivery of care for patients.

- Staff shortfalls would fall significantly by 2028 and would continue to fall, with sustained investment in education and training in line with this Plan, at a steadier rate over the rest of the modelled period, which means we will be materially reducing the NHS’s reliance on agency staff.

- With full implementation over the longer term, the NHS total workforce would grow by around 2.6–2.9% a year, with an expansion of the NHS permanent workforce from 1.4 million in 2021/22 to 2.2–2.3 million in 2036/37, including an extra 60,000–74,000 doctors, 170,000–190,000 nurses, 71,000–76,000 allied health professionals (AHPs), and 210,000–240,000 support workers alongside the expansion of new roles such as physician associates and nursing associates, and greater use of apprenticeships. If the Plan is fully implemented, by 2036/37, this will be equivalent to the number of nurses per 1,000 population growing to around 9.5, and the number of doctors per 1,000 population growing to around 4.3, in the NHS in England.

- A higher proportion of new joiners to the NHS workforce would come from domestic routes rather than from overseas and, within those, a greater proportion would train via apprenticeship routes. In 15 years’ time, we expect around 9–10.5% of our workforce to be recruited from overseas, compared to nearly a quarter now.

- Leaver rates would improve by around 15% over the course of the Plan, and retention will be at rates better than the average pre-pandemic.

- The NHS would be enabled to improve productivity, overcoming the impact from COVID-19, and improve to a level above the historical trend, with sustained and continued investment in workforce, technology, infrastructure and innovation.

Scope and key considerations

- We recognise that the challenges described are not unique to the NHS, and the NHS does not operate in a vacuum. There are many different factors outside the NHS’s control that impact on the demands it experiences.

- Pressure in social care, which impacts patient flow through the healthcare system and builds demand by increasing the burden of disease and complexity of conditions over the longer term.

- However, this Plan focuses on the workforce employed by the NHS and delivering NHS-funded services in NHS trusts and primary care. We recognise that people’s careers can span health and social care, and factor into the proposals that staff in the private, social care, social enterprise and voluntary sectors are critical to the overall provision of services and delivery of the best and most appropriate care for the population [see references 21, 22, 23, 24].

- This Plan’s actions are interdependent. For example, retention and productivity cannot improve to the degree this Plan projects without increasing the size of the workforce and the capacity of the NHS. Likewise, it is not exhaustive. The Plan does not cover every action needed to support workforce development across the NHS over the next 15 years. Rather, it is the first step in regular planning that will evolve and develop in line with service need.

- Beyond core terms and conditions, which are outside the scope of this Plan, we will need government to support this Plan by providing the necessary continued and sustained investment in infrastructure, reforming education funding and strengthening social care provision on which the success of this Plan depends.

- Infrastructure – Significant training expansion and workforce growth are only possible if there is sufficient physical capacity for staff to be trained in and work in. Labour productivity is dependent on the quality and capacity of physical and digital infrastructure. Government has invested in the New Hospital Programme, community diagnostic centres and surgical hubs. Building on these, continued and sustained investment in NHS estate and equipment, including in primary care and a rolling new hospital programme, will be critical to achieving the labour productivity ambitions in this Plan. It also requires sustained investment in technology and digital innovation to modernise the environment NHS staff work in.

- Education funding – NHS England and the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC) are working together to reform the funding of healthcare education and training provided nationally in England to ensure accountability, transparency and the best return on the additional investment set out as part of this NHS Long Term Workforce Plan.

- Social care provision – Health and care services are interdependent, and if efforts in this Plan to tackle the current challenges in the NHS are to yield success, then capacity needs to increase across both [see reference 25]. This Plan is predicated on access to social care services remaining broadly in line with current levels or improving. The government set out a vision for adult social care reform in the December 2021 white paper, [see reference 26] and allocated additional funding to support this. Earlier this year, an update was published which focused on improving the quality and accessibility of care [see reference 27].This confirmed funding of £250 million for workforce recognition and career development, including funding for continued professional development for registered nurses and other regulated professionals, and guiding principles to enable safe and effective delegation of healthcare activities to care workers.

- While the Plan’s model is founded on data, evidence and analysis, its projections are made with assumptions that are, by their nature, subject to a degree of uncertainty. This is unavoidable for any modelling over a 15-year timeframe. It is also dependent on decisions made by organisations outside the NHS; for example, local authorities that commission NHS services. To avoid a misleading impression of precision, the assumptions are often applied uniformly, without necessarily differentiating between geographical areas and, in some cases, professions and projections are reflected as ranges. We have, however, assessed community pharmacy and dental demand and supply separately, taking account of the unique circumstances in these settings. The model, and ranges presented, should be treated as strategic insights to inform policy choices relating to training, education, recruitment and retention.

- We will continue to develop the model and Plan, publishing a refreshed projection every two years, or aligned with fiscal events as appropriate.

- While we recognise the need for continued growth, this Plan does not cover the demand and supply of medical specialties, except for where these are already planned. This is partly because the available data is not yet sufficiently granular to give a clear enough picture for all specialisms to enable highly detailed national decisions on specialist workforce planning. It also reflects that it is incredibly difficult to predict which specialist roles will be most in demand in 15 years’ time, particularly where further work is needed to consider a future shift towards a more flexible specialist workforce. As this Plan is iterated, the objective is to establish the data and methodologies to enable a view to be formed with a richer and more granular range of information from across the NHS.

Next steps

- The Plan builds on the changes already happening in the NHS to have more people, working differently, in a compassionate and inclusive culture. The Plan sets out actions the NHS will begin implementing now, alongside proposals about how to close the anticipated staffing shortfalls in the longer term. We will work with government, stakeholders and local health systems to put the workforce on a sustainable footing to meet patients’ needs for the long-term.

- The merging of Health Education England, NHS Digital and NHS England has provided the opportunity to align and co-ordinate planning and action in the short and long term, so we can have the greatest possible collective impact for staff and, by extension, patients and citizens. In line with NHS England’s operating framework, [see reference 28] NHS England has an important role by providing co-ordinated support to equip systems to lead and innovate.

- This Plan is therefore intended to be the start of an ongoing programme of work that becomes an established part of how the NHS plans for, and delivers, its services for patients and the public. It is crucial we embed an integrated approach to planning and delivery, bringing together workforce planning with service and clinical strategies and financial planning for the long term, so we have a sustained and responsive approach that reflects changes in demand, services and wider factors. Following publication, we will continue to work with system leaders and stakeholders to refine the detail of the actions, and to support effective implementation and delivery of the ambitions in the Plan.

1. The case for change

- The size and shape of the NHS workforce need to change to meet patient need now and in the future. When a person turns to the NHS for help, it needs to have enough people with the right skills, and in the right place, to meet their needs.

- Rising demographic pressures and a changing burden of disease mean that demand is increasing and will be further impacted by the development in our ability to treat disease in areas like cancer or obesity. Maintaining the current size of the workforce, and the skills mix within, will not be sufficient to deliver the care needed in the future. Over the next 15 years, the population of England is projected to increase by 4.2%, but the number of people aged over 85 is projected to increase by 55% [see reference 29]. The use of health and social care resources rises rapidly with age. Between 25% and 50% of people aged over 85 will have frailty, compared to around 10% over 65 [see reference 30]. Average (public) health spending was five times greater for an 85-year-old than for a 30-year-old in 2015, [see reference 31] and for every 10 years beyond the age of 70, the risk of admission for an inpatient episode rises rapidly [see references 32, 33].

- People experiencing health inequalities develop long-term conditions earlier, accumulate them faster and live with them longer. This leads to a loss of productivity and higher healthcare expenditure. Stark variations in healthy life expectancy (HLE) exist; at birth for boys in the most deprived areas it is 52.3 years, compared with 70.5 years in the least deprived areas. Likewise for girls, HLE is 51.9 years and 70.7 years for the most and least deprived areas respectively (2018–2020 data), [see reference 34]. The proportion of patients with multimorbidity (two or more health conditions) is steadily rising and in higher income countries this increase is largely, but not exclusively, linked to age [see reference 35]. The increase in demand from an ageing population is not uniform across the UK, but concentrated outside metropolitan areas and in particular rural areas [see reference 36, 37. In 2037, a third of people aged over 85 will be living in rural communities like Cornwall, Somerset, Cumbria and North Yorkshire, compared to a quarter now. On current trends, two-thirds of those over 65 will have multiple health conditions, and a third of those people will also have mental health needs. We are also seeing more people from younger cohorts with multimorbidity, likely associated with low socio-economic status and deprivation, [see reference 38]. Multimorbidity challenges the specialised approach to medicine, which has improved our ability to successfully treat single diseases. As we move forward, we will increasingly need medical and other clinical professionals with generalist and core skills to manage and support patients with seemingly unrelated diseases. Additionally, government intends to publish a new major conditions strategy that will aim to improve prevention, diagnosis and treatment of six major conditions (cancer, cardiovascular diseases including stroke and diabetes, chronic respiratory diseases, dementia, mental ill health, musculoskeletal disorders).

- There is a clear need for the NHS workforce to continue to grow and evolve. There were over 112,000 vacancies across the NHS workforce in March 2023 (an 8% vacancy rate) but with significant variation across regions and professional groups. Moreover, vacancy data might even underestimate the true staff shortfall across the NHS. There is no perfect measure of workforce shortage at the national level currently. Vacancy statistics do not reflect the fact that in some instances temporary staffing will be deployed even where there are no recorded vacancies. The NHS employs 1.6 million people [see references 39, 40] and around a further 286,000 are training in the service at any given time [see reference 41]. The NHS workforce has seen significant growth since 2010 and has grown by 12% in the last three years [see references 42, 43]. However, only 26.4% of respondents to the 2022 NHS Staff Survey said there were sufficient staff in their organisation for them to do their job properly – a 11.9 percentage point decline from 38.3% in 2020 [see reference 44].

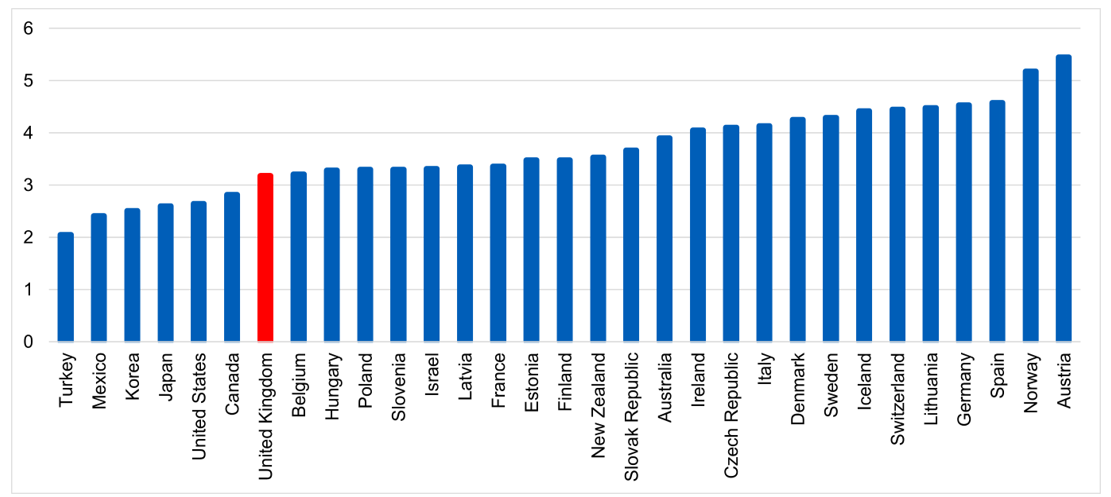

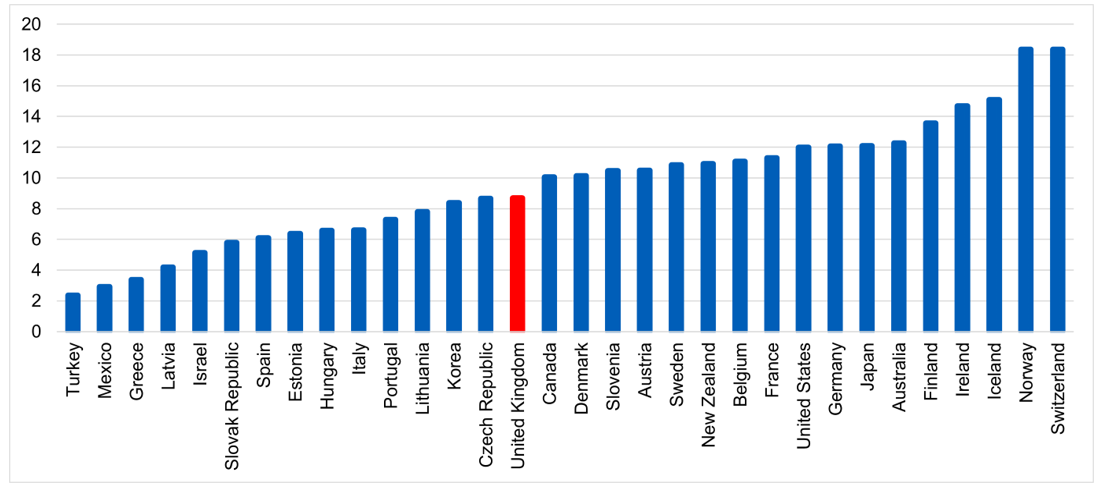

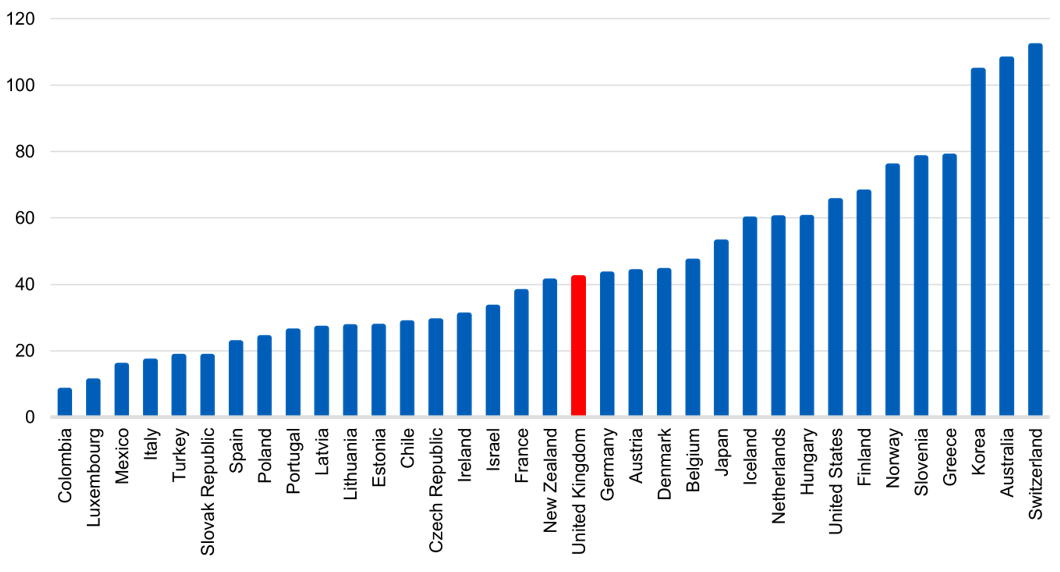

- Compared with other health systems internationally, the UK sits below the OECD average for the number of practising doctors as a proportion of the population [see reference 45] and we have fewer GPs per 1,000 population compared to most other OECD countries [see reference 46]. The UK has fewer than half the number of practising nurses compared to Norway and Switzerland, while Germany and Australia have 39% and 41% more nurses respectively (per 1,000 population), [see reference 47]. Global trends demonstrate that the health and care workforce is increasing as a proportion of total population across OECD countries and other international comparators, reflecting the changing demographic structure across comparable countries, [see reference 48]. Due to key factors such as differing health system types and structures, different skills mix models, variations in education and training and differences in statistical and regulatory arrangements, these comparisons should be interpreted cautiously and with recognition of these differing contexts. These comparisons are however helpful as an indication of possible similarities, differences and opportunities for learning.

Figure 2: Practising doctors per 1,000 population, 2021 (or latest available)

Data extracted May 2023

Figure 3: Practising nurses per 1,000 population, 2021 (or latest available)

Data extracted May 2023

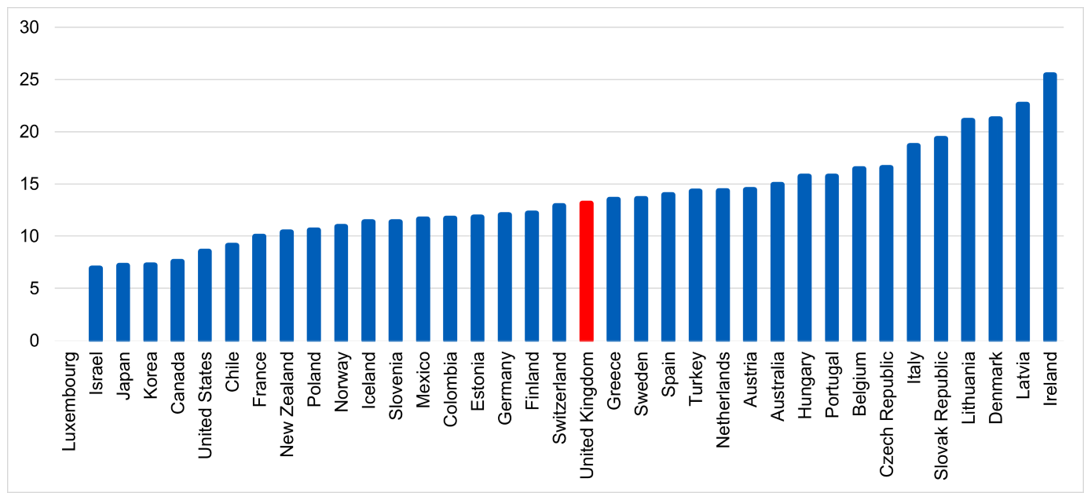

- Historically, over decades, growth in NHS services has not been matched by investment in the education and training pipeline. Despite increases in recent years, the UK sits below many other developed countries in terms of the number of people trained per size of population.

Figure 4: Medical graduates per 100,000 population, 2021 (or latest available)

Data extracted May 2023

Figure 5: Nursing graduates per 100,000 population, 2021 (or latest available)

Data extracted May 2023

- Attracting and retaining a highly engaged workforce is becoming more challenging and the NHS is operating in an increasingly competitive labour market. The COVID-19 pandemic saw NHS staff go above and beyond to care for patients, and during this time the number of staff leaving the service was low. However, this trend is now reversing. Notably, healthcare services are competing with other sectors of the economy to attract and retain staff. Staff in lower paid, direct entry positions – clinical and non-clinical – can often transfer relatively easily into other jobs in the economy with better pay, and greater flexibility and benefits.

- To fill service gaps and ensure safe staffing levels, the NHS has relied too much on temporary staffing. Over the three years up to 2021/22, expenditure on bank and agency staff has increased by 51% (from £3.45 billion to £5.2 billion) and 23% (£2.4 billion to £2.96 billion) respectively, reflecting some of the challenges of responding to the COVID-19 pandemic [see reference 53]. Use of agency staff is expensive and offers poor value for money for the taxpayer. There is also increasing evidence that use of temporary staffing – particularly agency staff – can negatively impact on patient and staff experience, and continuity of care [see reference 54].

- The NHS is particularly reliant on international recruitment to fill workforce gaps and deliver patient care in comparison to other healthcare systems globally [see reference 55]. The total proportion of NHS workers with non-UK nationalities (across all professions) has grown to over 17% (although there is significant variation between regions and staff groups), [see reference 56]. While employing international graduates supports the sharing of global learning and skills, and all international colleagues are highly valued, recent data shows a 2% increase in UK trained medical graduates joining the workforce since 2017, compared to a 121% rise in international medical graduates, [see reference 57]. International recruitment has supported necessary increases in some staff groups, such as doctors and nurses, but does not offer a universal solution to rising workforce demand; for some professions where scope of practice differs from England (for example, community nursing, mental health nursing, learning disability nursing, oncology and podiatry), overseas recruitment is not a readily available option.

- A heavy reliance on overseas staff leaves the NHS exposed to future global shocks and fluctuations in international workforce supply. The COVID-19 pandemic highlighted the fragility of using international recruitment to plug workforce shortages, and any future global shocks such as pandemics, armed conflicts and climate change may present similar challenges. The international healthcare labour market is likely to become increasingly competitive as healthcare systems around the world face increasing demand. It is estimated that between 2015 and 2050, the proportion of the world’s population over 60 years will nearly double from 12% to 22%, and that by 2050, 80% of older people will be living in low- and middle-income countries [see reference 58]. This will drive up global demand for healthcare staff, making it more challenging to recruit from overseas. Other countries such as Canada and the USA do not currently rely on international recruitment to the same extent as the NHS.

However, any change in the workforce requirements of those countries could constrain the NHS’s ability to compete internationally, [see reference 59] particularly if they offer better opportunities for pay or quality of life, limiting the NHS’s competitive advantage.

- Demographic changes will present some opportunities when it comes to recruiting to the future healthcare workforce. There will be a ‘bulge’ in the 18- year-old population over the next few years, which possibly will not be seen again for the rest of the century [see reference 60]. As such, there is an imminent narrow window to offer as many routes as possible to school leavers into careers in healthcare.

- The current NHS workforce largely concentrates on responding to care and health needs rather than prevention. The NHS Long Term Plan [see reference 61] identified the service changes needed to deliver an NHS fit for the 21st century. These include boosting primary and community care, focusing on population health, integration and prevention, investing in mental healthcare, diagnosing cancer earlier and making sure everyone with cancer has access to a clinical nurse specialist or other support worker, and having an efficient NHS focused on outcomes. However, according to OECD data, in the UK, more healthcare spending is allocated to hospital services than its peers, and less to preventative medicine, residential and outpatient care [see reference 62]. We also know that the overall balance of the NHS workforce has remained somewhat resistant to change in recent decades. For example, the number of full-time equivalent (FTE) nurses working in adult hospital nursing grew by almost 4.6% in the year to February 2023, while the number working in community nursing grew by 2.7% [see reference 63]. In other words, NHS resources are being used to treat an increasingly sick population, with a declining proportion being used to prevent people from becoming unwell in the first place. The UK has one of the highest admission rates for asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, for example [see reference 64]. Beyond meeting patient needs and expectations, the current skills mix within teams could better optimise productivity and value, and empower more existing staff to use their full scope of practice.

- New and emerging roles are growing but not at a sufficient rate to fundamentally alter the overall shape of the workforce. In future, healthcare teams will continue to be led by clinical experts, but wider skills will be needed to help offer personalised, responsive care to patients, supporting them to be independent. This may involve digital monitoring of remote care and coaching to help patients manage their health, as well as expert practitioners to support rehabilitation, and drive care planning and decision-making. In addition to providing better care for patients, broader multiprofessional teams will mitigate some of the challenges in recruiting to traditional workforce roles.

- Upskilling the workforce and offering opportunities for enhanced, advanced and consultant practice will help retain NHS staff delivering clinical care, grow the total number of senior clinical decision-makers and enable the delivery of better patient care. Traditional career structures for healthcare professionals can be too rigid, with some staff opting to leave clinical practice because they feel they cannot progress their careers. Associate and support roles across professions will also help widen access to NHS careers, with a particular emphasis on apprenticeships and targeted recruitment, supporting a diversity of new entrants who reflect the communities we serve. As the number of skilled roles within the existing workforce increases, a parallel focus will be needed on recruiting to entry level roles to maintain balanced teams.

- The impact of COVID-19 is still affecting delivery, and this is likely to be one of the biggest challenges for NHS recovery over the coming years. The pandemic caused long-lasting disruption to NHS services, resulting in additional demand on the workforce while constraining the NHS’s ability to deliver care for patients. Various contributing factors had an impact, including the direct effects of managing COVID-19, delays to discharge and longer non-elective length of stay (therefore constraining elective capacity), and higher staff sickness and absence. Comparable pressures are being seen in mental health services. The proportion of adults experiencing depression almost doubled during the pandemic [see reference 65]. By June 2022, there were 1.23 million people waiting for their second contact from a mental health service and there are increasing needs of children who require NHS mental healthcare [see reference 66].

- These challenges are not unique to the NHS. The adult social care sector in England employs around 1.5 million people, with a further 165,000 posts currently vacant [see reference 67]. Care workers make up most of the adult social care workforce; they are less well paid on average than people performing equivalent roles in the NHS [see reference 68] and are leaving at rates higher than they are replaced [see reference 69]. There are also fewer nurses in the sector compared to 10 years ago and Skills for Care estimates that 44% of nurses in adult social care left their role in 2021/22, [see reference 70]. While putting in place mitigations and increasing the number of staff working in direct entry roles will form a critical part of this Plan, this should not come at the expense of exacerbating workforce shortages that exist elsewhere in the social care sector.

- Pressures in adult social care directly impact on the NHS. Workforce challenges in adult social care mean that meeting people’s physical and mental healthcare needs at home or in the community is challenging, leading to poorer health outcomes and increased likelihood of hospital admissions. They also contribute to delayed discharges, which impacts on the wider health system.

- The introduction of integrated care partnerships provides a unique opportunity. NHS systems and local authorities will be able to work more effectively together to provide integrated care that meets the health and wellbeing needs of the population they serve. This will include integrated workforce planning to best develop and deploy staff; for example, through opportunities for joint teams, joint training and rotation between NHS and social care settings. This will be important for services like public health, which improve population health and prevent ill health, and are vital as the population becomes sicker and has greater healthcare needs. Workforce planning, development and training for public health areas such as sexual and reproductive health and alcohol and drug treatment should benefit from improved joint working between ICBs and local authorities.

- Developments in science, research, technology, digital and data will continue. The evidence available suggests developments such as genomics and artificial intelligence (AI) will transform our ability to prevent, diagnose, treat and manage disease, supporting a shift towards better prevention, health and wellbeing, and more personalised, empowered care [see references 71, 72]. To deliver the benefits of these advances, we need to upskill the workforce with core skills and increase the number of expert roles across digital, genomics and personalised care. The use of more diverse roles and skills, combined with enabling technology, will lead to more care being delivered remotely, closer to home or in the community, such as in virtual wards, and will enable more teams to work across organisational boundaries.

- Developments in AI may increase productivity by giving the workforce ‘the gift of time’, [see reference 73] as more routine tasks are automated, augmenting rather than replacing clinical professions. These advances will not materially lessen the need for staff overall but, combined with a greater focus on prevention, could help reduce the forecasted rate of growth in workforce demand.

- Upskilling the workforce is key to unlocking the potential of science, research and technology to deliver the care of the future. There is a growing convergence between what people say they want (more personal, preventative and productive care), the advancements to make this possible, and the collaborative place-based systems to deliver it. With the right capacity and skills, NHS staff will be able to make this a reality.

- Staff want to work in multiprofessional teams, with time to provide personalised, proactive care to patients. The 2022 NHS Staff Survey [see reference 74] results demonstrated that while progress has been made in key areas, the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and long running trends such as workload pressures mean there is still a lot of work to do together to make the ambitions of the NHS People Promise [see reference 75] a reality for everyone.

- We must do more to ensure staff, learners and volunteers have equal opportunity within a compassionate and inclusive culture. We know having a diverse workforce will enable us to provide better care for our diverse patient groups and reduce inequalities. The NHS workforce is more diverse than at any other point in its history and we want everyone to have a positive experience working in the NHS, but we recognise this is not always the case. Progress has been made in some areas. For example, ethnic minority representation at very senior manager level in NHS trusts has increased from 7.9% in 2020 to 10.3% in 2022, and in 2022 13.2% of NHS trust board members were from an ethnic minority background compared to 10.0% in 2020, as reported in the NHS Workforce Race Equality Standard [see reference 76]. However, there is still much to do. Higher levels of disabled staff experience bullying, harassment or abuse from managers, and women tend to have worse experiences than men related to harassment, discrimination from a manager and equal opportunities for progression [see reference 77]. White applicants are 1.54 times more likely to be shortlisted for a job compared to applicants from ethnic minority backgrounds [see reference 78]. NHS staff who are LGBT are still much more likely to face physical violence, bullying and harassment in their workplace than other staff [see reference 79].

The scale of the challenge

- The NHS Long Term Workforce Plan offers an approach to project our potential staffing needs for the short, medium and long term and better understand the scale of the challenge to come over the next 15 years. This will inform national policy decisions about how to ensure the NHS can sustainably meet the needs of patients.

- After factoring in ambitious expectations for improved labour productivity (above the long-term trend), our assessment is that, with no further intervention, the shortfall will grow to 260,000–360,000 FTEs by 2036/37.

- Most professions will see current shortfalls grow without the interventions in this Plan, but there will be notable shortfalls:

- Within medical staffing, the model assumes some boost in GP numbers as a result of interventions in recent years, but the projected growth over the long term fails to keep up with expected demand. In 2022/23 the overall FTE GP workforce (including GPs in training) grew by 1.4%; however, there were 512 (1.8%) fewer FTE fully qualified GPs in April 2023 compared to April 2022 [see reference 80]. The shortfall in fully qualified GPs is projected to be around 15,000 by 2036/37 without intervention.

- Among nursing staff, by 2036/37 there will be a 37,000 FTE shortfall in community nurses compared to a 6,500 FTE shortfall in 2021/22. The current shortfall in mental health nursing is of particular concern, with the greatest vacancy rates in inpatient services, impacting on patient safety and quality of care. The total mental health nursing shortfall will reach 15,800 FTEs in 2036/37. The learning disability nursing shortfall will grow to 1,200 FTEs and for critical care nurses it will be 4,200 FTEs in 2036/37, up from 3,800 FTEs now. This is due to fewer nurses taking up training and education in these areas and limited opportunities to fill the domestic shortfall with international recruitment.

- Among the allied health professions (AHPs), the greatest shortfalls will be seen for podiatrists, paramedics (and ambulance technicians), occupational therapists, diagnostic radiographers and speech and language therapists (both adult and child), with limited supply growth projected. This is due to the education and training pipeline not keeping pace with expected demand.

- Within the non-registered workforce, healthcare support workers are anticipated to have the largest shortfall between demand and supply. This is driven by limited supply growth and a high leaver rate for existing staff.

- The starting point for assessing the shortfall between workforce supply and demand is the reliance on temporary staffing in the NHS in 2021/22, which is estimated to have been approximately 150,000 FTEs. In other words, the total demand for workforce is defined by all the workforce deployed (including substantive and temporary staff), and supply is defined by staff in post (substantive). This is not a perfect measure and for some professions other methodologies have been used. For GPs, temporary staffing is not a comparable measure due to the different contracting mechanisms. Therefore, historical patient-to-qualified GP ratios are used to estimate the opening position. In some professions and specialties, access to the temporary market is limited and therefore the use of temporary staffing may underestimate the actual workforce shortfall. In such cases, growth rates should reflect the workforce challenges each profession faces. In addition, the starting point does not take into account unmet demand, and the modelling attempts to address this in future growth to recover services and performance. Overall, temporary staffing is chosen as it better reflects demand for workforce than vacancy rates (which are subject to organisational variances and reporting practices.

- To estimate the future workforce demand, known and expected changes to NHS demand have been applied to the starting point. The drivers of demand are presented in Table 1 and include the additional demand required to recover NHS services and improve performance. Supply projections consider historical trends in supply growth (joiner and leaver rates), the education and training pipeline, planned expansions and observed flows in international recruitment.

- To mitigate the anticipated shortfall position over the 15-year timeframe, this Plan sets out actions that will be taken in the near term, alongside an assessment of the required additional actions over the medium to long term. These are described against three broad areas: train – growing the workforce (Chapter 2); retain – embedding the right culture and improving retention (Chapter 3); and reform – working and training differently (Chapter 4).

Table 1: Demand drivers underpinning modelling

| 1. Demographic growth and the burden of disease |

| Aligned with ONS demographic growth projections, and non-demographic growth based on analysis of growing complexity of needs and historical trends. |

| 2. The service ambition to move care upstream and deliver more NHS care out of hospitals will increase demand in the community |

Community and primary care growth reflects NHS Long Term Plan and service plans to move care upstream, investing more in prevention and early intervention, as well as rehabilitation and reablement to mitigate avoidable growth in secondary care. These incorporate existing service plans including Professor Sir Mike Richards’ review of diagnostics demand, and virtual ward and intermediate care expansion |

| 3. Additional demand required to improve access and performance |

| In acute care, this means tackling long waits in line with the Elective Recovery Plan; and reducing emergency care pressures, by improving flow through the system, reducing acute bed occupancy and length of stay, and improving ambulance call response times, in line with the Urgent and Emergency Care Recovery Plan. This assumes a return to pre-pandemic level of length of stay, which will require social care capacity to stabilise and increase alongside intermediate care capacity. For mental health, this means growth rates based on the NHS Mental Health Implementation Plan and Mental Health Investment Standard. For maternity services, this means reflecting the Ockenden review of maternity services [see reference 81] recommendations in determining the opening shortfall for midwives. Growth reflects changing birth rates as well as higher complexity of need. For primary care, this means using the 2015 ratio of patients to qualified GPs to assess the demand for GPs, and growth in primary care takes into consideration the service plans to enhance access to primary care, such as the Primary Care Access Recovery Plan. For community services, this means improving access and meeting the needs of an ageing population. |

2. Train – Growing the workforce

Overview

- Our assessment is that, compared to 2022, domestic education and training will need to increase between 50% and 65% by 2030/31 (through a variety of training routes). This level of expansion is put forward because, despite accounting for improvements in staff retention and productivity, under current trends, at the end of 2036/37 there would still be a workforce shortfall and significant reliance on international recruitment. And with interest in courses currently surpassing the student places available, there is considerable opportunity to achieve this level of growth.

- To begin realising this expansion, additional funding of more than £2.4 billion cumulatively will be invested in education and training over the next six years, on top of current education and training budgets. This will support a 27% expansion in training places by 2028/29. The growth set out in the Plan builds on the steps already being taken to train more people, and builds on investment already planned, which is increasing from £5.5 billion to £6.1 billion over the next two years.

- For each profession, the Plan sets out a bespoke approach to optimise domestic supply by detailing expansions to entry routes and increasing training and education to meet demand (Table 2), especially for professions with a heavier reliance on international recruitment. This means estimating the potential maximum education and training intake for each profession, and balancing apprenticeships with more traditional university courses. When looking to reduce levels of international recruitment, the Plan has considered the maximum level of international recruitment that could be influenced nationally (such as excluding non-UK nationals who do not need a visa to work in the NHS) alongside the level of overseas recruitment the NHS would always want to retain to give providers flexibility and a source of wider and diverse talent. With these considerations, the Plan sets a reasonable trajectory to increase domestic training and recruitment to materially reduce workforce shortfalls by 2028/29, and largely close shortfalls for most professions by 2031/32. For each profession, as well as assessing the longer-term growth ambitions, the Plan sets out the immediate steps that will be taken to expand education and training for each group, alongside the funding that will be committed to support this. The phasing of planned expansion recognises that additional education and training capacity will take time to put in place, balancing the need to address workforce shortfalls as soon as possible with deliverability.

- Several professions will, even with targeted interventions, likely see medium-term shortfalls and may continue to rely on temporary staff (such as mental health nursing, learning disability nursing and podiatry) or international recruitment (such as adult nursing and doctors). National programmes will examine options for the future of these professions, including how targeted international recruitment or training, and changes in roles or skills mix can help to meet demand.

- Some professions have received recent investment to increase education and training, reducing the magnitude of the expansion they will need compared to other professions. For example, paramedic training places have increased from around 2,100 in 2015 to just over 3,850 in 2022 [see reference 82]. This means that a continued projected average supply growth of 3.7–4.0% per year is possible within the 15-year modelling period with an increase in training places of 5–18% a year.

- Full expansion cannot happen immediately, but rather by incremental but significant increase in education and training capacity. Successful expansion will be contingent on there being an expanded and fully trained supervisory workforce to support evolving learner and workforce need. The initial steps being taken to achieve this are detailed throughout this chapter. Several important reforms will need to accompany expansion, to improve the experience of learners and ensure clinicians of the future have the skills they need to provide high quality care.

- The Plan assumes that the whole health education pipeline will need to grow at least in line with the demand required to deliver NHS services. The proposed training intakes have been adjusted to accommodate this additional demand (Annex C). The proportion of staff who go from training to non-NHS employers is assumed to remain the same. Service models may change the balance of care provided in NHS settings compared to the independent sector or within social care, in either direction, but by increasing the whole pipeline the entire sector has flexibility across regulated health professions irrespective of the organisation services are commissioned by or from.

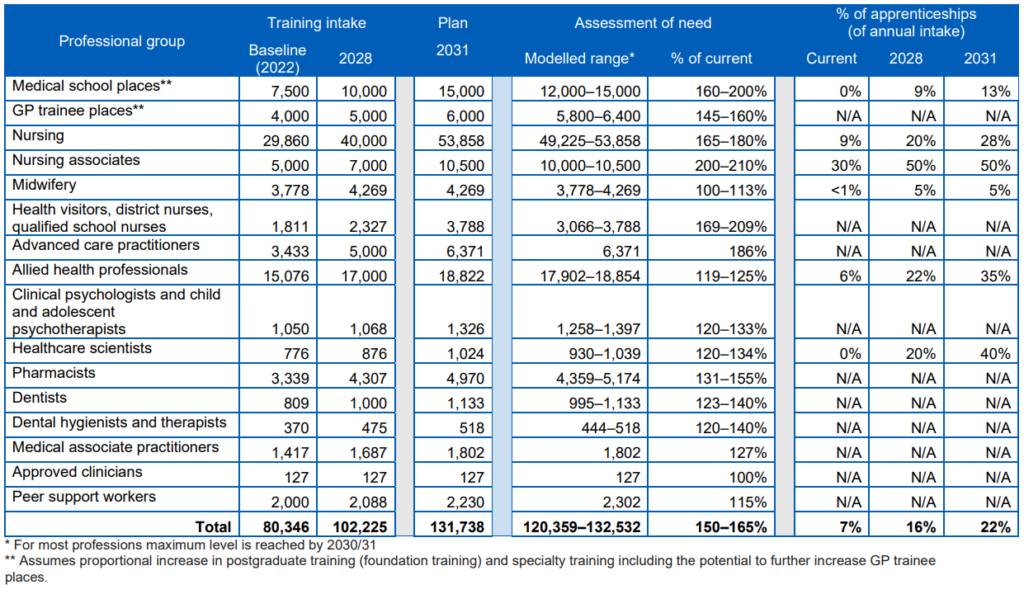

Table 2: Increase required in education and training by profession

* For most professions maximum level is reached by 2030/31

** Assumes proportional increase in postgraduate training (foundation training) and specialty training including the potential to further increase GP trainee places.

Medical training

- The required increase in medical school places is estimated to be 60–100%, providing 12,000–15,000 places by 2030/31. This can be delivered by the expansion of existing medical schools and establishment of new ones, and the introduction of medical degree apprenticeships. The scale of expansion set out would require close working with medical schools, higher education institutes and the further education sector, the regulator and other stakeholders. This Plan sets out an ambition to double the number of medical school training places, taking the total to 15,000 places a year by 2031/32. Over the next six years, we will work towards this level of expansion by increasing medical school places by a third, to 10,000 by 2028/29.

- To meet the demand for GPs, this Plan outlines a need to increase the number of GP specialty training places by 45–60% by 2033/34. Our ambition is to increase the number of places by 50% to 6,000 by 2031/32. In 2018 the government expanded the number of medical school places by 1,500 and the first of these graduates are now starting to join the workforce. This Plan commits to initially growing GP specialty training by 500 places in 2025/26, timed so that more of these newly qualifying doctors can train in primary care. Further expansion of GP specialty training places will then take place with 1,000 additional places (5,000 in total) in 2027/28 and 2028/29. This will offer the same opportunity to a bigger pool of doctors graduating as a result of the increase in undergraduate places outlined in this Plan.