First published: 12 January 2016 (as Policy book for primary medical services)

First update: 9 November 2017

Previous update: May 2022

Current update: July 2024

Executive summary

This Primary medical services policy and guidance manual (PGM) has been updated to reflect ongoing development and changes in the commissioning and contractual management landscape. This suite of policies should be followed by all commissioners of NHS primary medical services. This approach ensures that all commissioners, providers and most importantly patients are treated equitably, and that NHS England and its commissioners meet their statutory and/or delegated duties.

NHS England is committed to reviewing this PGM regularly.

The Health and Care Act 2022

The Health and Care Act 2022 gained royal assent on 28 April 2022. It:

a. formally established NHS integrated care systems (ICSs) and gave their governing bodies – integrated care boards (ICBs) – a broader range of responsibilities. This was done at the same time as abolishing clinical commissioning groups (CCGs)

b. introduced powers for the new NHS provider selection regime (PSR), which have now established a new set of rules for arranging NHS services to give decision makers a more flexible and proportionate decision-making process for selecting providers to deliver healthcare services to the public, including primary medical services

The inception of ICBs from 1 July 2022 has brought a change to who commissions primary medical services. To support commissioners, NHS England has reviewed and updated the 2022 version of the PGM and made a number of additions and amendments.

Integrated care systems

With primary medical services successfully delegated to CCGs for some time, this means ICBs assumed delegated responsibility for primary medical services on establishment under a new delegation agreement incorporating, which now include all dental (primary, secondary and community), general optometry, and pharmaceutical services.

The aim of the delegation is to empower ICBs to join up health and care, improve population health and reduce health inequalities.

Under delegation ICBs have responsibility for commissioning and contract monitoring GP services in their locality/systems, with NHS England maintaining overall accountability.

Commissioner in this PGM means NHS England or ICBs under delegated authority.

NHS provider selection regime

As of Monday 1 January 2024, the NHS provider selection regime (PSR) is in force.

The PSR is set out in the Health Care Services (Provider Selection Regime) Regulations 2023, which the Department of Health and Social Care introduced into Parliament on 19 October 2023.

NHS England has published statutory guidance to support implementation of the PSR regulations, setting out what relevant authorities must do to comply with them. This includes some sector specific considerations, including primary care (annex C).

The PSR seeks to ensure that decisions about who provides healthcare services are:

- Made in the best interest of patients, taxpayers, and the population.

- Robust and defensible, with conflicts of interests appropriately managed.

- Made transparently.

- Compliant with the rules of the regime as set out in NHS England guidance.

As this PGM update was made prior to confirmation of the PSR coming into effect. The guidance will be updated in due course to ensure it better reflects the PSR. Queries about the PSR should be sent to psr.development@nhs.net .

General

This PGM is divided into 4 parts (A, B, C and D); namely:

- part A – excellent commissioning and partnership working

- part B – general contract management

- part C – when things go wrong

- part D – general

Each part has headed numbered chapters with headed numbered sub-sections, which can be found in the contents list on the left of this page.

Reference to external legislation or guidance may be required to ensure access to current wording mitigating the need to update the PGM where such changes, and hyperlinks may be provided.

Where templates are provided these may be by hyperlink if published elsewhere or embedded as extractable documents for easier onward use.

This guidance supersedes all previous versions of the PGM.

Part A – excellent commissioning and partnership working

1. Introduction

1.1 Introduction

1.1.1 NHS England became responsible for direct commissioning of primary medical services on 1 April 2013 and since then, the emergence of co-commissioning has seen all CCG taking on delegated authority until 30 June 2022. Thereafter, ICBs act as the commissioner under a delegation agreement.

This policy has been reviewed and refined considering:

- feedback from commissioner users

- engagement with stakeholders

- contractual and regulatory changes

- coming into force of the Health and Social Care Act 2022

1.1.2 This PGM provides the policies to support a consistent and compliant approach to primary medical services commissioning across England.

1.1.3 The PGM identifies sections which describe mandatory functions (ie those absolutely defined in legislation and law) versus those which are provided as guidance or best practice.

1.1.4 The PGM is supported by a suite of e-learning modules to provide commissioners a deeper appreciation of some of the more complicated commissioning or contract management scenarios they may face and complement the content within the PGM. A link to each can be found in the following sections and you will need to create a user account with NHS England’s e-Learning for Healthcare to access them.

- part B – chapter 8 contract variation: approving GP practice boundary changes

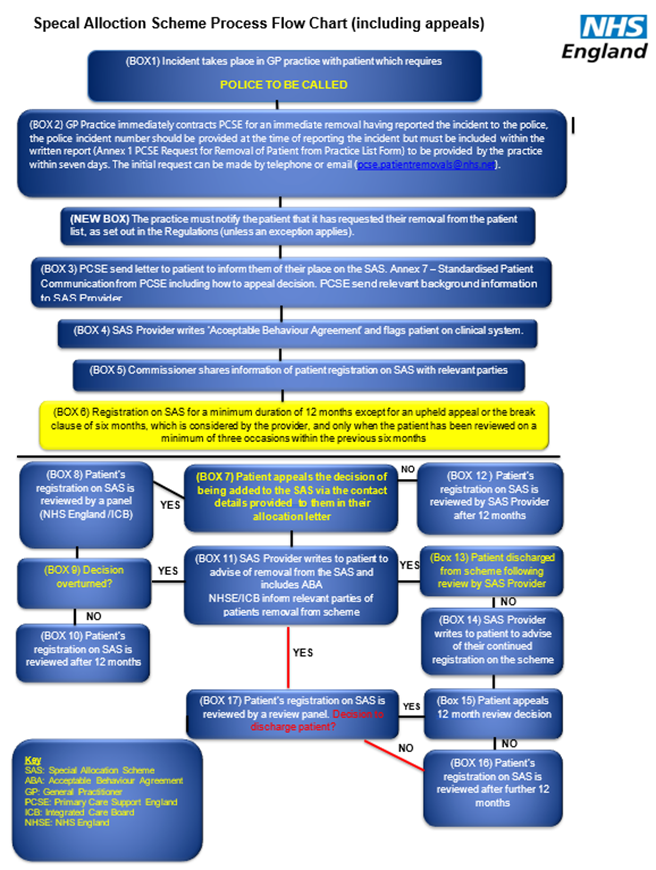

- part B – chapter 7 special allocation schemes (SAS)

- part B – chapter 8 contract variation: GP contractor changes: incorporation and novation

- part C – chapter 2 unplanned/unscheduled and unavoidable practice closedown: handling threats to the continuity of GP services

- part B – developing a primary medical services procurement strategy

Each module should take between 30 to 40 minutes to complete and there is a short self-assessment at the end of each module with results provided immediately.

1.2 Structure

1.2.1 A number of new policies have emerged since the policy book was first published and these have been incorporated into this manual. The PGM is structured into 4 main sections for ease of navigation. These are:

- part A – excellent commissioning and partnership working

- part B – general contract management

- part C – when things go wrong

- part D – general

1.2.2 NHS England will update and refine policies periodically and following changes in legislation, contracts or central policy and guidance. Users of this PGM are advised this is a controlled document and the most up to date version should always be used. That is, the version which is published on NHS England’s website.

1.3 Transitional arrangements

1.3.1 This PGM replaces all previous versions. In addition, we have embedded as chapters some other related policy/guidance that have been published by NHS England as standalone documents since the original ‘policy book’ was published in July 2016. The processes and procedures set out in this PGM must be followed where a matter arises after the date of publication of this PGM.

1.3.2 Where a matter arose prior to the publication of this PGM (and the parties are therefore following a previous policy) the parties should continue to follow that previous policy as this would have been the expectation of the parties at the time.

1.3.3 Parties following a previous policy should consider switching to the relevant policy set out in this PGM if there is a natural transitional point in the matter and provided all parties agree.

2. The legislation, abbreviations and acronyms

2.1 Links to legislation and other relevant law

2.1.1 The legislation and law applying to primary medical services may be amended from time to time. It is important that users of the PGM are familiar with the relevant in force published documentation.

2.1.2 The PGM must be read in conjunction with the relevant law, which may not be repeated in full in this PGM.

2.1.3 However, to assist users of the PGM, the links below provide access to the relevant documents content pages from where the user may find the appropriate section, regulation etc.:

- Equality Act 2010

- Equality Act 2010 (Specific Duties and Public Authorities) Regulations 2017

- National Health Service Act 2006

- Health and Social Care Act 2012

- Health and Care Act 2022

- The National Health Service (General Medical Services Contracts) Regulations 2015

- The National Health Service (Personal Medical Services Agreements) Regulations 2015

Note: while www.legislation.gov.uk updates legislation, at any point in time there may be outstanding amendments therefore users are advised to ensure they are familiar with current amendments pending any updating as appropriate.

2.1.4 The law published in directions can be found on the gov.uk website and, at the time of publishing this PGM, the links below provide access to some relevant documents as originally published as a whole from where the user may find the appropriate direction, paragraph etc.:

- Alternative Provider Medical Services Directions (2022)

- General Medical Services Statement of Financial Entitlements Directions (2023)

- The Primary Medical Services (Directed Enhanced Services) Directions 2022

Note: any subsequent amending directions are not updated, and users are advised to ensure they are familiar with current amendments until any subsequent publication as appropriate.

2.2 Abbreviations and acronyms

The following abbreviations and acronyms are used in the PGM:

- APMS – alternative provider medical services

- APMS directions – alternative provider medical services directions

- CCG – clinical commissioning group

- COSHH – control of substances hazardous to health

- CQC – Care Quality Commission

- GMS – general medical services

- GMS regulations – The National Health Service (General Medical Services Contracts) Regulations 2015

- GMS SFE – general medical services statement of financial entitlements directions

- GP – general practitioner

- HWB – health and wellbeing board

- ICB – integrated care board

- ICS – integrated care system

- LMC – local medical committee

- NBM – new business models

- NHS – Act National Health Service Act 2006

- PSR – provider service regime

- NHSR – NHS Resolution

- PCA – Primary Care Appeals (Part of NHSR)

- PCSE – Primary Care Support England (delivered by Capita on behalf of NHS England)

- PCN – primary care network

- PHSO – Parliamentary and Health Service Ombudsman

- PMS – personal medical services

- PMS Regulations – The National Health Service (Personal Medical Services Agreements) Regulations 2015

- TUPE – Transfer of Undertakings (Protection of Employment) Regulations 2006

Staff working with the NHS may also find this acronym buster helpful (which provides a broader list of NHS acronyms in use beyond this document), alongside our understanding the NHS section.

3. Commissioning described

3.1 Background and delegated commissioning (2014 – 2022)

3.1.1 In May 2014, NHS England invited CCGs to come forward with expressions of interest to take on an increased role in the commissioning of primary medical services empowering and enabling CCGs to improve primary care services locally for the benefit of patients and local communities.

3.1.2 Known as co-commissioning, CCGs collaborated closely with NHS England to ensure that decisions taken about healthcare services were strategically aligned across the local health economy. Joint commissioning arrangements allowed CCGs and NHS England to effectively plan and improve the provision of out of hospital services for the benefit of patients and local populations.

3.1.3 Delegated commissioning was an opportunity for CCGs to assume full responsibility for commissioning general practice services. Legally, NHS England retained the residual liability for the performance of primary medical services commissioning. Therefore, NHS England required robust assurance that its statutory functions were discharged effectively.

3.1.4 The following primary medical functions were included in CCG delegated arrangements:

- GMS, PMS, APMS (including the design of PMS and APMS contracts, monitoring of contracts, taking contractual action, such as issuing breach/remedial notices, and removing a contract)

- newly designed enhanced services (“Local Enhanced Services (LES)” and “Directed Enhanced Services (DES)”)

- design of local incentive schemes as an alternative to the Quality and outcomes framework (QOF)

- the ability to establish new GP practices in an area

- approving practice mergers

- making decisions on ‘discretionary’ payments

3.1.5 Delegated commissioning arrangements exclude reserved functions such as individual GP performance management (medical performers’ list for GPs, appraisal, and revalidation). NHS England retaining responsibility for the administration of payments and list management.

3.2 ICB delegated commissioning arrangements

3.2.1 From July April 2022, ICBs assumed delegated responsibility for primary medical services excluding Section 7A Public Health functions. From April 2023 ICBs assumed delegated responsibility for dental (primary, secondary and community), general ophthalmic services and pharmaceutical services.

3.2.2 NHS England retain reserved functions such as performers list management, and wider aspects of professional regulation. Further functions retained nationally include:

- identifying national priorities, setting outcomes, and developing national contracts or contractual frameworks

- maintaining national policies and guidance that will support ICBs to be effective in their delegated functions

- delivering support services

3.3 Primary care policies

3.3.1 For the purposes of the primary care policies, the commissioner of the primary care service is not referred to by name but simply as the “commissioner”. This reflects the fact the identity of the commissioner in an area is a delegated ICB (see Executive summary on the Health and Social Care Act 2022), which abolished clinical commissioning groups and created ICBs.

3.3.2 Although ICBs may assume the role of the commissioner for the purposes of the policies, for ICB delegation, legally NHS England retains the residual liability for the performance of primary medical services commissioning. However, there will be matters which have not been delegated to ICBs or are not able to be carried out by an ICB in which case the commissioner will be NHS England.

3.3.3 ICB under delegated commissioning arrangements, an ICB will have agreed on a delegation agreement with NHS England. This document will set out for what matters the ICB has decision-making responsibilities. Where the delegation agreement sets out obligations on the ICB, eg liaising with NHS England in relation to managing disputes, the relevant primary medical policy refers to the delegation agreement and highlights relevant points.

Equality and health inequalities

3.3.4 ICBs and NHS England have legal duties in respect of equality and health inequalities. Supporting guidance has been issued within the 2020-2021 planning and contracting guidance, Guidance for NHS commissioners on equality and health inequalities legal duties. A number of data and analysis tools are published by Public Health England (eg the Inequalities calculation tool). In the commissioning and operational implementation of primary medical services due regard should be given to these duties. Further detail is also provided in the next section.

3.4 Primary care networks

3.4.1 Primary care networks (PCNs) build on the core of current primary care services and enable greater provision of proactive, personalised, coordinated and more integrated health and social care, with greater collaboration between general practice and other local system partners including community pharmacy, local authorities, social care, community providers, mental health providers and voluntary services. Clinicians describe this as a change from reactively providing appointments to proactively caring for the people and communities they serve. PCNs can also help to provide stability and resilience for practices.

3.4.2 Refreshing NHS plans for 2018-19 and the NHS Long Term Plan prefigured the formal intention that every practice should be part of a PCN, covering the whole country. This was delivered as part of Investment and evolution: the five-year framework for GP contract reform which introduced from 1 July 2019 a new directed enhanced service – “the network contract DES”. Its goal is to ensure general practice plays a leading role in every PCN and enables much closer working between PCNs and their integrated care board.

3.4.3 PCNs are based on GP registered lists and are made up of a practice or practices (and possibly other providers) typically serving natural communities of around 30,000 to 50,000 people. These parameters mean that PCNs are small enough to provide the personal care valued by both patients and GPs, but large enough to have impact and economies of scale through better collaboration between practices and others in the local health and social care system.

3.4.4 Find out more through case studies from across the country where primary care networks are already making a difference to staff and patients.

3.4.5 In March 2023 (and updated yearly), NHS England published the Network contract DES – contract specification – PCN requirements and entitlements, setting out eligibility requirements and the rights and obligations of practices, PCNs and commissioners under the DES. A range of additional information to assist commissioners and providers in further developing PCNs is also available on the NHS England GP contract page.

4. General duties of NHS England (including addressing health inequalities)

4.1 Introduction

4.1.1 This chapter outlines the general duties that NHS England must comply with that are likely to affect the decisions it takes regarding the provision of primary care.

4.1.2 ICBs carrying out commissioning under delegated authority do so on behalf of NHS England. ICBs need to comply with NHS England’s legal duties when doing this – this is set out in the delegation agreement. Therefore, this chapter is also relevant to ICBs.

4.1.3 In many instances the duties placed on NHS England are mirrored by similar duties placed on ICBs. We have highlighted the equivalent ICB duty. However, this note does not cover any further ICB duties that apply only to ICBs and not to NHS England.

4.1.4 There are many general duties on commissioners. It is important that decision-makers are familiar with all these duties because if a duty has not been complied with when a decision is taken, that decision can be challenged in the courts on the grounds that it is unlawful.

4.1.5 This guidance looks at the general duties that commissioners are required to comply with that are most applicable to primary care, providing examples to illustrate how they might affect decision making.

4.1.6 As has been noted, under delegation arrangements NHS England retains the legal responsibility for compliance with the duties in respect of primary medical services commissioning. Accordingly, NHS England will require assurance that its statutory functions are being discharged effectively by an ICB. This underlines the importance of compliance with the duties outlined in this chapter.

4.1.7 Below is a summary of the duties that are covered by this chapter. The chapter (from 2 onwards) goes on to look at each of the duties in more detail. A table of contents is also provided for clarity.

Duties covered in this chapter – table of contents

- summary of duties covered by this chapter

- equality and health inequalities duties

- other non-equality and health inequalities related duties

Summary of duties covered by this chapter

Equality and health inequalities duties

Equality Act 2010

The Equality Act 2010 prohibits unlawful discrimination in the provision of services on the grounds of age, disability, gender reassignment, marriage and civil partnership, pregnancy and maternity, race, religion or belief, sex, and sexual orientation. These are the “protected characteristics”.

As well as these prohibitions against unlawful discrimination, the Equality Act 2010 requires commissioners to have “due regard” to the need to:

- eliminate discrimination that is unlawful under the Equality Act

- advance equality of opportunity between people who share a relevant protected characteristic and people who do not share it; and

- foster good relations between persons who share a relevant protected characteristic and persons who do not share it

This can require NHS England to take positive steps to reduce inequalities.

The duty is known as the public sector equality duty or PSED (see section 149 of the Equality Act 2010). The Equality Act 2010 also imposes (through regulations made under the Act) particular inequality related duties on commissioners. Failure to comply with these specific duties will be unlawful.

NHS Act 2006 (as amended by the Health and Social Care Act 2012)

Under the NHS Act 2006 (as amended by the Health and Social Care Act 2012) commissioners also have a duty to have regard to the need to:

- reduce inequalities between patients with respect to their ability to access health services; and

- reduce inequalities between patients with respect to the outcomes achieved for them by the provision of health services

- (in respect of NHS England, see section 13G of the NHS Act 2006; and, in respect of ICBs, see section 14T of the NHS Act 2006)

Other non-equality and health inequalities related duties

The “regard duties”

In addition to the above, there are other obligations on commissioners to “have regard” to particular factors. These are set out in the NHS Act 2006 (as amended by the Health and Social Care Act 2012).

The other “regard duties” are:

- the duty to have regard to the desirability of allowing others in the healthcare system to act with autonomy and avoid imposing unnecessary burdens upon them, so far as this is consistent with the interests of the health service (in respect of NHS England, see section 13F of the NHS Act 2006)

- the duty to have regard to the need to promote education and training of those working within (or intending to work within) the health service (in respect of NHS England, see section 13M of the NHS Act 2006; and, in respect of ICBs, see section 14Z of the NHS Act 2006)

- the duty to have regard to the likely impact of commissioning decisions on healthcare delivered in areas of Wales or Scotland close to the border with England (in respect of NHS England, see section 13O of the NHS Act 2006)

The “view to duties”

The “view to duties” are:

- the duty to act with a view to delivering services in a way that promotes the NHS constitution (in respect of NHS England, see section 13C(1)(a) of the NHS Act 2006; and, in respect of ICBs, see section 14P of the NHS Act 2006)

- the duty to act with a view to securing continuous improvement in the quality of services in health and public health services (in respect of NHS England, see section 13E of the NHS Act 2006; and, in respect of ICBs, see section 14R of the NHS Act 2006)

- the duty to act with a view to enabling patients to make choices about their care (in respect of NHS England, see section 13I of the NHS Act 2006; and, in respect of ICBs, see section 14R of the NHS Act 2006)

- the duty to act with a view to securing integration, including between health and other public services that impact on health, where this would improve health services (in respect of NHS England, see section 13N of the NHS Act 2006; and, in respect of ICBs, see section 14Z1 of the NHS Act 2006)

The “promote duties”

The “promote duties” are:

- the duty to promote awareness of the NHS Constitution among patients, staff and members of the public (in respect of NHS England, see section 13C(1)(b) of the NHS Act 2006; and, in respect of ICBs, see section 14P(1)(b) of the NHS Act 2006)

- the duty to promote the involvement of patients and carers in decisions about their own care (in respect of NHS England, see section 13H of the NHS Act 2006; and, in respect of ICBs, see section 14U of the NHS Act 2006)

- the duty to promote innovation in the health service (in respect of NHS England, see section 13K of the NHS Act 2006; and, in respect of ICBs, see section 14X of the NHS Act 2006)

- he duty to promote research and the use of research on matters relevant to the health service (in respect of NHS England, see section 13L of the NHS Act 2006; and, in respect of ICBs, see section 14Y of the NHS Act 2006)

The “involvement duty”

Commissioners have a duty to make arrangements to secure that service users and potential service users are involved in:

- the planning of commissioning arrangements by commissioners

- the commissioners’ development and consideration of proposals for changes to commissioning arrangements, if the implementation of the proposals would impact on the range of health services available to service users or the manner in which they are delivered

- the commissioners’ decisions affecting the operation of commissioning arrangements, if those decisions would have such an impact

(in respect of NHS England, see section 13Q of the NHS Act 2006; in respect of ICBs, see section 14Z2 of the NHS Act 2006)

Duty to act fairly and reasonably

Commissioners have a duty to act fairly and reasonably when making its decisions. These duties come from case law that applies to all public bodies.

Duty to obtain advice

Commissioners have a duty to “obtain appropriate advice” from persons with a broad range of professional expertise (in respect of NHS England, see section 13J of the NHS Act 2006; and, in respect of ICBs, see section 14W of the NHS Act 2006)

Duty to exercise functions effectively

Commissioners have a duty to exercise their functions effectively, efficiently and economically (in respect of NHS England, see section 13D of the NHS Act 2006; and, in respect of ICBs, see section 14Q of the NHS Act 2006)

Duty not to prefer one type of provider

Commissioners must not try to vary the proportion of services delivered by providers according to whether the provider is in the public or private sector, or some other aspect of their status.

4.2 Equality and health inequalities duties

4.2.1 This section considers equality and health inequality duties. First, the duties under the Equality Act 2010 are considered followed by the other health inequality-related duties.

a) Equality Act 2010

4.2.2 Commissioners have both general and specific equality related duties under the Equality Act 2010. The general duty can be found in section 149 of the Equality Act. It is known as the public sector equality duty or the PSED. The specific duties are imposed on commissioners by secondary legislation, namely the Equality Act 2010 (Specific Duties and Public Authorities) Regulations 2017. Further details on both the PSED and the 2017 Regulations are provided in the sections below.

4.2.3 The duty to have regard to the PSED will arise when commissioners are exercising their functions. A commissioner will be open to legal challenge if they are unable to demonstrate their regard to the PSED when publishing guidance or policies or making decisions. A failure to comply with the prescribed duties outlined in the 2017 regulations will also be unlawful.

The protected characteristics

4.2.4 The Equality Act 2010 prohibits unlawful discrimination in the provision of services (including healthcare services) on the basis of “protected characteristics”. The protected characteristics are:

- age

- disability

- gender reassignment

- marriage and civil partnership

- pregnancy and maternity

- race

- religion or belief (which can include an absence of belief)

- sex

- sexual orientation

4.2.5 Unlawful discrimination can also occur if a person is at a disadvantage because of a combination of these factors.

Unlawful discrimination

4.2.6 There are broadly 4 types of discrimination in the provision of services that are unlawful under the Equality Act 2010:

- Direct discrimination services are not available to someone because they are, eg not married, over 35, a woman. Apart from a few limited exceptions, direct discrimination will always be unlawful, unless it is on the grounds of age and the discrimination is a proportionate means of achieving a legitimate aim.

- Indirect discrimination occurs when commissioners apply a policy, criterion or practice equally to everybody, but which has a disproportionate negative impact on one of the groups of people sharing a protected characteristic, and where the complainant cannot themselves comply. The classic example is a height requirement, which is likely to exclude a much greater proportion of women than men because women are on average significantly shorter. Requirements that require people to behave in a certain way will amount to indirect discrimination if compliance is not consistent with reasonable expectations of behaviour. For example, a requirement not to wear a head covering would be indirectly discriminatory on the grounds of religion, even though followers of religions which require a head covering are physically able to remove it. Indirect discrimination is not unlawful if it is a proportionate means of achieving a legitimate aim.

- Disability discrimination occurs if a person is treated unfavourably because of something “arising in consequence of their disability”. This captures discrimination that occurs not because of a person’s disability per se (eg a person has multiple sclerosis) but because of the behaviour caused by the disability (eg use of a wheelchair). So, an inability of someone with multiple sclerosis to access services when using their wheelchair could be an instance of disability discrimination.

- Disability discrimination is not unlawful if it is a proportionate means of achieving a legitimate aim.

- A failure to make “reasonable adjustments” for people with disabilities who are put at a substantial disadvantage by a practice or physical feature. The duty also requires bodies to put an “auxiliary aid” in place where this would remove a substantial disadvantage e.g. a hearing aid induction loop. The duty to make reasonable adjustments might, for example, require NHS England or a ICB to make consultation materials available in braille. However, some care is needed here. People with disabilities have a right to access services in broadly the same way as people without disabilities, so far as is reasonable. Offering a telephone consultation to a wheelchair using patient who is prevented from accessing a clinic by steps may in fact be unlawful discrimination rather than a reasonable adjustment. The wheelchair user should be able to access services in broadly the same way as others i.e. by attending practice premises for a consultation.

(Unlawful discrimination is also prohibited in the field of employment and other areas but these are not covered in this guidance).

Public sector equality duty

4.2.7 The Equality Act 2010 requires commissioners to have “due regard” to the need to:

- eliminate discrimination that is unlawful under the Act

- advance equality of opportunity between people who share a protected characteristic and people who do not share it

- foster good relations between persons who share a protected characteristic and persons who do not share it

4.2.8 These objectives are often referred to as the “three aims” of the PSED. The aims are amended for the protected characteristic of marriage and civil partnership. Commissioners do have to have due regard to eliminate unlawful discrimination based on marriage and civil partnership (the first aim). However, they are not required to have due regard to the need to advance equality of opportunity or foster good relations in relation to marriage and civil partnership (the second and third aims).

4.2.9 Compliance with the three aims of the PSED can require a commissioner to take positive steps to reduce inequalities. In this regard the Act permits treating some people more favourably than others but not if this amounts to unlawful discrimination (what is meant by unlawful discrimination is considered below). The PSED has been used successfully on many occasions to challenge changes to services.

4.2.10 This means that a commissioner has a duty to help eliminate any unlawful discrimination practised by the providers of primary care, eg through requiring premises to be accessible. Failing to use its negotiating power to secure such changes could be seen as a breach by a commissioner of the PSED, as well as a breach of the non-discrimination rules by the service provider.

Example

After a site visit the commissioner becomes aware that consulting rooms in a GP surgery are no longer accessible to those with limited mobility as they have been moved upstairs. The commissioner decides that as there are no downstairs consulting rooms and there is no lift or stair lift, this is a breach of the practice’s duty to make reasonable adjustments under the Equality Act. This in turn is a breach of the practice’s duty under its contract with the commissioner to comply with legislation. In order to comply with the PSED the commissioner takes steps to ensure that the practice complies with its Equality Act duties by raising the issue informally and issuing a breach notice if the problem is not remedied.

Example

A hearing impaired patient complains to the commissioner about their experience with a local (NHS commissioned) provider. The patient was unable to communicate effectively with the provider because of their hearing impairment. When the patient suggested that the provider obtain a sign language interpreter to translate for them this was refused.

It is likely that the provider will be in breach of their obligations under the Equality Act 2010 to make reasonable adjustments. In order to comply with the PSED NHS England takes steps to investigate and enforcement action if needed.

4.2.11 Carrying out appropriate equality and health inequalities impact assessments (EHIAs) is usually critical to proving discharge of the PSED, although they are not as such a legal requirement. This is because if there is no assessment of the impact of a possible change on groups with protected characteristics, it is very difficult to argue that the commissioner had the impact properly in mind when it made its decision. This is the case even if the impact on protected groups is minimal.

4.2.12 It is not always easy to assess the equality impact. A robust service user involvement exercise will help the commissioner to identify any issues. It is advisable to ask question(s) directly aimed at equalities issues. In many cases, it is advisable to take special steps to reach seldom heard groups affected by the decisions (eg by working with local voluntary, community and faith sector groups and holding meetings in community venues). The more likely a decision is to disproportionately affect a protected group, the more important it is to get feedback from that group about the decision. Undertaking a literature search can also be helpful to see what evidence is available. NHS England’s Equality and Health Inequalities Unit has a resource hub with information.

4.2.13 The PSED means that the commissioner must consider equalities issues when making decisions. In some cases, there may be a solution that causes less disadvantage to a protected group but for other reasons is undesirable. In these situations, it is important to acknowledge the disadvantage, work towards reducing the negative impact caused and be clear about why the decision was taken. This may include outlining costs concerns. It also makes sense to monitor the situation, eg does the demographic of service users change as a result of the decision and timetable a formal review in, eg a year’s time.

4.2.14 There are a few themes arising from the cases we have seen on the application of the PSED (and similar duties in previous legislation).

- A need to explicitly recognise that the PSED applies, and equalities issues need to be considered.

- The duty is an ongoing one – to be considered at all stages of decision-making not just at the end.

- A need to be clear about the factors driving a decision, even if these are unpalatable, eg budgetary pressures.

- A need to analyse in some detail the impact of a proposed policy or decision so that the public authority has a clear idea of who is affected and how. Statements of impact need to be supported by evidence where possible.

- If a decision is made that will impact negatively on a protected group, that should be acknowledged, and the rationale explained.

- There should be a detailed consideration as to how any negative impact of the decision could be mitigated. If the steps identified are not practicable, this should be explained.

- The duty must be complied with at the time of the decision. After the event reasoning is rarely allowed so a record should be made at the time about how equalities issues were considered.

4.2.15 Further guidance on the PSED can be found on NHS England’s Equality and Health Inequalities Unit resource hub. Additionally, the Equality and Human Rights Commission publish a wealth of information.

Guidance on the PSED can also be found on the Equality and Human Rights Commission website.

The Equality Act 2010 specific duties

4.2.16 In addition to the PSED NHS England and ICBs are also required to comply with the specific duties contained in the Equality Act 2010 (Specific Duties and Public Authorities) Regulations 2017.

4.2.17 The 2017 Regulations came into force on 31 March 2017. The 2017 Regulations replace the first set of specific duty regulations made in 2011.

4.2.18 The 2017 Regulations among other things require commissioners to publish:

- equality objectives that should be achieved to comply with the PSED (regulation 5). This has to be done by 30 March 2018 and the objectives need to be updated once every 4 years. ICBs should ensure that they are familiar with NHS England’s equality objectives, which have been published on the resource hub.

4.2.19 The Equality and Human Rights Commission can, under sections 31 and 32 of the Equality Act 2006, investigate and enforce a failure to comply with the PSED or the specific duties. Alternatively, a failure to comply with the general and specific duties could be challenged by way of judicial review. Such a claim could be brought by a person or group directly affected by a failure to comply with these duties.

b) Health inequalities duties and the NHS Act 2006 (as amended by the Health and Social Care Act 2012)

4.2.20 Under the Health and Social Care Act 2012, commissioners are required to have regard to the need to:

- reduce inequalities between patients with respect to their ability to access health services

- reduce health inequalities between patients with respect to the outcomes achieved for them by the provision of health service

4.2.21 When making decisions about primary care, particularly about service changes, decision-makers will need to bear in mind the impact on health inequalities. To do this the commissioner will need some data on existing health inequalities, and to consider whether its decision can be used to diminish these. A vast amount of data is available, eg JNSA’s; Right Care packs to help commissioners identify health inequalities in their area.

4.2.22 The key point is that the commissioner can show (through documentation, principally an EHIA) that the impact a decision will have on health inequalities has been considered, and that its decision is based on some relevant data and evidence.

4.2.23 NHS England has made available several resources to assist organisations to find out about information, resources and action being taken to reduce health inequalities in England. Local joint strategic needs assessments (JSNA) prepared by local health and wellbeing boards, ICB system oversight framework indicators and NHS RightCare can be valuable sources of information about local health inequalities.

The other non-equality and health inequalities related duties:

4.3 The regard duties

Introduction

4.3.1 The “have regard”, “act with a view to” or “promote” duties under the National Health Service Act 2006 form a loose hierarchy of legal duties:

- The duty to have regard means that when taking actions, a certain thing must be considered.

- The duty to promote means action must be taken that actually achieves an outcome. Additionally, it is possible to promote something by encouraging others to do it.

- The duty to act with a view to means that action must be taken with a purpose in mind.

4.3.2 In contrast to the promotion duties and the view to duties, the regard duties apply to every action of a commissioner where it is carrying out its primary care functions. (Pausing there, the duty will not normally apply to “private law” decisions that would be taken by any private sector organisation – leasing estate etc.)

4.3.3 The PSED cases are the best guide that we have to how a court would interpret a commissioner’s regard duties under the NHS Act 2006. We can learn from these that:

- Commissioners who have to take decisions must be made aware of their duty to have regard to the various issues outlined in the duties. Failure to do so will render the decision unlawful.

- The regard duties must be fulfilled before and at the time that a particular decision is being considered. If they are not, any attempts to retrospectively justify a decision as consistent with the regard duties will not be enough to discharge them.

- Commissioners need to engage with the regard duties with rigour and with an open mind.

- It is good practice for the decision-maker to refer to the regard duties.

- It is not possible for the commissioner to delegate the duties down to another organisation to comply with. This applies in respect of NHS England delegated arrangements for primary care services (see above). NHS England will always have to comply with its duties under the NHS Act 2006, even if an ICB is carrying out commissioning on its behalf. However, it is a requirement of the delegation agreement that ICBs act in such a way that enables NHS England to comply with its duties. If a commissioner acts through contractors, it must ensure as necessary that they act consistently with the duties.

- The regard duties are continuing ones that apply throughout decision-making. It is not enough to only “rubber stamp” a decision by reference to the regard duties at the end of a decision-making process. The regard duties need to be borne in mind throughout.

- It is crucial to keep an adequate record of how the regard duties are considered. If records are not kept it will make it more difficult, evidentially, for the commissioner to persuade a court that the duties imposed have been fulfilled.

4.3.4 One key point to understand is that there is no obligation to achieve the object of the regard duties, eg it is not unlawful not to eliminate health inequalities (although equally, if health inequalities persist and widen, that fact would need to inform consideration of the regard duty). Nor does the commissioner have the luxury of “pausing” the health service while it investigates health inequality or any other matter. The duties are to have regard, not to achieve perfection, and this is a practical rather than an academic exercise.

Reduce health inequalities

4.3.5 This duty has been discussed above. It is listed here for completeness, as it is one of the regard duties under the NHS Act 2006.

Act with autonomy

4.3.6 NHS England has a statutory duty to have regard to the desirability of allowing others in the healthcare system to act with autonomy and avoid imposing unnecessary burdens upon them, so far as this is consistent with the interests of the health service.

Example

NHS England is considering commissioning new primary care services in a particular area. When deciding what type of contract it wants to award (GMS, PMS or APMS) it should weigh in the balance the desirability of the extra autonomy a PMS or APMS contract offers.

Promote education and training

4.3.7 Commissioners have a duty to have regard to the need to promote education and training of those working within (or intending to work within) the health service.

Impact in areas of Wales or Scotland

4.3.8 NHS England has a duty to have regard to the likely impact of commissioning decisions on healthcare delivered in areas of Wales or Scotland close to the border with England. This will clearly be relevant for those working in NHS England regional teams that border Wales or Scotland. NHS England will also need to comply with the duty when making national strategic decisions about the delivery of primary care – that affect bordering areas as well as others.

Example

The commissioner is considering commissioning new primary care services for a town in England close to the border with Scotland. It is concerned that many of the local residents have difficulty in accessing local primary care services, the nearest practice being based over the border in Scotland. That provider is difficult to access by public transport and in the winter the short route is often impassable. To comply with its duty to have regard to the likely impact of commissioning decisions on healthcare delivered in areas Scotland close to the border with England, the commissioner discusses the impact that commissioning services on the English side of the border would have on the Scottish provider. It takes this impact into account when it makes its decision about the commissioning of services.

4.4 The promote duties

4.4.1 It is helpful to look next at the promote duties. These are:

- the duty to promote awareness of the NHS Constitution among patients, staff and members of the public (in respect of NHS England, see section 13C(1)(b) of the NHS Act 2006; and, in respect of ICBs, see section 14P(1)(b) of the NHS Act 2006)

- the duty to promote the involvement of patients and carers in decisions about their own care (in respect of NHS England, see section 13H of the NHS Act 2006; and, in respect of ICBs, see section 14U of the NHS Act 2006)

- the duty to promote innovation in the health service (in respect of NHS England, see section 13K of the NHS Act 2006; and, in respect of ICBs, see section 14X of the NHS Act 2006)

- the duty to promote research and the use of research on matters relevant to the health service (in respect of NHS England, see section 13L of the NHS Act 2006; and, in respect of ICBs, see section 14Y of the NHS Act 2006)

- a decision which is positively contrary to achieving the relevant outcome might breach a promote duty unless there was some compelling reason to adopt it. In this situation, if the decision is being made by NHS England or by ICBs under delegated authority, the NHS England legal team should be contacted for further guidance

- additionally, some decisions will be obvious opportunities where, eg patient involvement could easily be promoted. In such cases the safest course of action is to ensure that this is done

4.4.2 To meet the duty a commissioner does not have to do everything itself – be more innovative, improve its use of research data etc. It can meet the duty by encouraging other people to do things.

Example

A commissioner decides to run a competition to reward GP practices that are innovative in their use of telehealth devices – smart medical devices that transmit data from a patient to their treating clinician, without the need for the patient to attend surgery. The winners will be showcased so that other practices can follow their lead. This helps to meet the duty to promote innovation in the health service. If a request was received by a commissioner, for example, extra funding to support the implementation of a local telehealth initiative they would not be obliged to support it because of the duty to promote innovation. That duty has already been met by the commissioner in a different way.

4.5 The view to duties

4.5.1 The “view to duties” are:

- the duty to act with a view to delivering services in a way that promotes the NHS constitution (in respect of NHS England, see section 13C(1)(a) of the NHS Act 2006; and, in respect of ICBs, see section 14P of the NHS Act 2006)

- the duty to act with a view to securing continuous improvement in the quality of services in health and public health services (in respect of NHS England, see section 13E of the NHS Act 2006; and, in respect of ICBs, see section 14R of the NHS Act 2006)

- the duty to act with a view to enabling patients to make choices about their care (in respect of NHS England, see section 13I of the NHS Act 2006; and, in respect of ICBs, see section 14R of the NHS Act 2006)

- the duty to act with a view to securing integration, including between health and other public services that impact on health,

- where this would improve health services (in respect of NHS England, see section 13N of the NHS Act 2006; and, in respect of ICBs, see section 14Z1 of the NHS Act 2006)

4.5.2 the duty to exercise its functions with a view to securing that health services are provided in an integrated way where it considers that this would:

- improve the quality of those services (including the outcomes that are achieved from their provision)

- reduce inequalities between persons with respect to their ability to access those services, or

- reduce inequalities between persons with respect to the outcomes achieved for them by the provision of those services

(In respect of NHS England, see section 13N of the NHS Act 2006; and in respect of ICBs, see section 14Z1 of the NHS Act 2006.)

4.5.3 In many ways the considerations for these duties and the promote duties are the same. One difference is that while a promote duty can be met by encouraging others to achieve it (eg encouraging GP practices to make better use of telehealth devices), with the view to duties the actions have to be carried out by the commissioner.

4.5.4 The view to duties are less onerous than the promote duties because they do not require the commissioner to achieve a particular outcome (although that would be desirable) – only to do something that aims to achieve it. This is in contrast to the promote duties, which require an outcome to be achieved.

4.5.5 The view To duties are most likely to affect strategic decisions taken at directorate level within NHS England. Provided the commissioner can show that within the totality of its activities there has been significant action taken with the intention of achieving the outcomes that the commissioner is required to have a view to, the duty is discharged.

4.5.6 As with the promote duties, decision-makers on the ground should be wary of doing something which actively goes against one of the goals set out in the view to duties. In this situation, if the decision is being made by NHS England or by an ICB under delegated authority, the NHS England legal team should be contacted for further guidance. Also, if there is a clear opportunity to help deliver one of the view to objectives, it is best to take it.

4.6 The involvement duty

Overview

4.6.1 Under sections 13Q of the NHS Act 2006, NHS England has a statutory duty to ‘make arrangements’ to involve the public in the commissioning services for NHS patients. (This duty is also placed directly on to ICBs under section 14Z2.)

4.6.2 Section 13Q applies to:

- the planning of commissioning arrangements

- the development and consideration of any proposals that would impact on the manner in which services are delivered to individuals or the range of services available to them

- decisions that would impact on the manner in which services are delivered to individuals or the range of services available to them

4.6.3 The section 13Q duty only applies to plans, proposals and decisions about services that are directly commissioned by NHS England. This includes GP, dental, ophthalmic, and pharmaceutical services. However, under delegated authority ICBs must act in a way that enables NHS England to comply with the 13Q requirements.

4.6.4 (The section 14Z2 duty applies in relation to any health services which are, or are to be, provided pursuant to arrangements made by an ICB in the exercise of the ICB’s own functions, ie commissioning of secondary care.)

The commissioners’ arrangements for public involvement

4.6.5 The statutory duty to ‘make arrangements’ under section 13Q of the NHS Act 2006 is essentially a requirement to make plans and preparations for public involvement.

4.6.6 NHS England has set out its plans as to how it intends to involve the public in the following publications:

- The patient and public participation policy

- The statement of arrangements and guidance on patient and public participation in commissioning.

- The framework for patient and public participation in primary care commissioning

4.6.7 These publications set out and explain the arrangements NHS England has in place:

- corporate infrastructure – how public involvement is embedded in the way that NHS England is constituted and carries out its business

- involvement initiatives – initiatives designed to involve the public in strategic planning and the development of policy or other aspects of NHS England’s activities

- monitoring arrangements – a step-by-step process to help commissioners identify whether the section 13Q applies and decide whether sufficient public involvement activity is already in place or whether additional public involvement is required

- responsive arrangements – guidance to commissioners on how to make arrangements for public involvement where monitoring has indicated that such arrangements are required

4.6.8 As well as setting out the above arrangements, which commissioners should follow, the documentation is regularly reviewed and updated and contains useful resources for commissioners, including:

- details of existing corporate infrastructure and involvement initiatives that could be drawn upon by commissioners to involve the public in their commissioning activities

- reference to NHS England’s framework for involving patients and the public in primary care commissioning, which includes resources developed especially for primary care

- resources to help commissioners identify whether section 13Q applies, put in place appropriate arrangements for public involvement and avoid legal challenges

- guidance on a variety of topics that often arise, such as what ‘public involvement’ means, how to involve the public, who to involve, when involvement should take place, urgent decisions, and joint involvement exercises

- case studies based upon primary care scenarios

- summaries of related legal duties

- details of how to seek further advice if needed

4.6.9 The documentation is intended to be used by both commissioners (who need to understand and comply with the arrangements when commissioning services) and the public (to understand how NHS England involves the public in its commissioning of services). As noted, for ICBs commissioning under delegated authority from NHS England, these arrangements are supplementary to their own requirement to have in place arrangements for public involvement under section 14Z2 of the NHS Act 2006.

4.7 Duty to act fairly and reasonably

4.7.1 Commissioners have a duty to act fairly and reasonably when making decisions. These duties come from case law that applies to all public bodies.

Acting fairly

4.7.2 Normally, to act fairly a commissioner will need to act in accordance with its own policies and relevant policies published by NHS England. For ICBs commissioning under delegated authority from NHS England, this will include NHS England policies concerned with the commissioning of primary care. A commissioner can depart from guidance if there is good reason to do so. In this scenario, the commissioner will need to explain the situation fully to the people and organisations affected and give them a chance to provide their views on the procedure to be followed. This will include why it wants to depart from the usual policy and what it will do instead.

4.7.3 Commissioners also need to be careful about keeping promises made to contractors or the public, eg that there will be a public consultation before any final decision is made on closing a particular pharmacy. It is sometimes (but not always) possible to depart from such promises. Therefore, care should be taken about giving any clear commitments to a particular course of action until the commissioner is sure that it is what it wants to do. If a commissioner is considering departing from a commitment it has given to do a particular thing or follow a particular type of process, then, if the decision is being made by NHS England or by an ICB under delegated authority, the NHS England legal team should be contacted for further guidance.

4.7.4 It is also important to act proportionately, taking into account any adverse impact on patients and/or contractors.

Acting reasonably

4.7.5 The commissioner must take all relevant factors into account when making its decisions and exclude irrelevant factors. It is up to the commissioner how much weight it gives competing considerations and may give a factor no weight at all. The key point is that all the relevant factors are identified and documented.

Example

The commissioner has to decide whether to approve a practice’s application to stop opening on Wednesday evening and open on Saturday morning instead. The practice is based in an area with a high Jewish population. Relevant factors in this decision include whether services will become more or less accessible as a result of the change, any adverse impact on people with protected characteristics (is the Jewish population disadvantaged as Saturday falls on the Jewish rest day?) and any costs implications for the commissioner. An example of an irrelevant factor is that the commissioner has been promised some good publicity by the practice if it agrees to the change.

4.7.6 The reasons for the commissioner’s decisions also need to “stack up”. It is important for the commissioner to document its reasons for a decision as the commissioner needs not only to act reasonably but be able to show that it has acted reasonably by reference to contemporaneous documents. This means that, particularly where a controversial decision is being made the thinking behind the decision needs to be carefully documented.

4.8 The duty to obtain advice

4.8.1 A commissioner has a duty to “obtain appropriate advice” from persons with a broad range of professional expertise (in respect of NHS England, see section 13J of the NHS Act 2006; and, in respect ICBs, see section 14W of the NHS Act 2006)

4.8.2 This means that decision-makers need to collect appropriate information before making decisions. If the commissioner does not have the information it needs, then it should seek out appropriate advice. In many cases, it will not be necessary to do this as all the necessary information is to hand.

4.8.3 The duty is most relevant to strategic decisions taken at the directorate level within NHS England, where decision-makers will need to document how they obtain advice from those with professional expertise (some of whom maybe employees or secondees).

4.9 The duty to exercise functions effectively

4.9.1 The commissioner has a duty to exercise its functions effectively, efficiently and economically (in respect of NHS England, see section 13D of the NHS Act 2006; and, in respect of ICBs, see section 14Q of the NHS Act 2006).

4.9.2 This is a statutory reformulation of a duty that has been contained for many years in Managing public money and its predecessors. If the commissioner has complied with the other duties in this guidance – in particular, the duty to act reasonably – it is highly unlikely that it will breach this duty.

4.10 The duty not to prefer one type of provider

4.10.1 NHS England must not try and vary the proportion of services delivered by providers according to whether the provider is in the public or private sector, or some other aspect of their status (section 13P). ICBs must also act in accordance with this duty when they are commissioning under delegated authority from NHS England.

4.10.2 This means that the commissioner must focus on the services delivered by an organisation and its sustainability. It should not make choices about contractors based solely on their status as, for example, company, partnership, public sector, private sector, charity or not for profit organisation.

5 Working together – commissioning and regulating

5.1 Introduction

5.1.1 This chapter is intended to inform commissioners of work to establish a robust and practical joint working framework.

5.2 Background

5.2.1 Alongside the publication of the GP Forward View (NHS England, 2016), a statement of intent was published by the main national regulatory and assurance bodies, committing to working together with professional bodies and those using services in the development of a shared view of quality in general practice. This would provide the basis of a joined-up approach to monitoring and improvement of quality.

5.2.2 The Regulation of General Practice Programme Board was established in June 2016 to:

- coordinate and improve the overall approach to the regulation of general practice in England by bringing together the main statutory oversight and regulatory bodies and delivering a programme of work which will streamline working arrangements and minimise duplication

- provide a forum for sign-up by statutory bodies to a common framework – a shared view of quality – which will be co-produced with the professions and the public

5.3 Implementation

5.3.1 The Care Quality Commission (CQC), NHS England, and NHS Clinical Commissioners (NHSCC), with the support of the General Medical Council (GMC), published a joint working framework in 2018.

5.3.2 The framework recognises that in many areas’ relationships between commissioners and CQC are working well; in other areas, the framework is intended to help provide structure and support for new relationships with examples of good practice.

5.4 Existing good practice and interim principles

5.4.1 Significant steps have already been taken to streamline processes and share information:

- NHS England regularly share eDec data and information with CQC

- NHS England will share eDec data with all commissioners, including analysis and outlier reports to help commissioners target support locally

- CQC share inspection rating updates every week with NHS England

- CQC share inspection schedules with commissioners wherever possible

- commissioners share local information and intelligence with CQC and NHS England

- in some areas commissioners work closely with GP practices prior to inspections to support them

5.4.2 Collaborative working arrangements:

5.4.3 Positive working relationships are critical for ensuring successful partnership working. Commissioners and CQC have established some formal mechanisms for ensuring successful collaborative working, but these should not be seen as the only means by which those relationships can be developed. We also recognise the role of quality surveillance groups and other forums that have been established for information sharing in some areas of the country.

5.4.4 It is recognised that telephoning the right person at the right organisation at the right time is the best means of developing those relationships and avoiding duplication wherever possible. It is important that commissioners engage with and know their local contacts.

5.4.5 Existing good practice:

- all parties will be transparent, and we will ensure information governance and data protection principles are adhered to without exception and we will ensure GP practices are fully sighted on this

- commissioners should actively and effectively communicate with each other and CQC to ensure GP practices are not overburdened, eg to avoid the situation whereby a commissioner contract visit overlaps with a CQC inspection

- commissioners should keep in regular contact with CQC throughout the year and more targeted and regular communication on the run-up to inspection or annual review

- commissioners should actively engage with and support GP Practices pre- and post-inspection.

5.5 Why

5.5.1 The system of medical regulation has evolved over time, rather than having been designed from a single agreed blueprint. There is a perception within the medical profession that it is over-regulated, with too many bodies setting standards and imposing requirements with potential for regulatory overlap. A lack of clarity about which body is responsible for which areas of monitoring and regulation carries a risk of duplication, but also of potential gaps in the system which is designed to ensure patient safety.

5.5.2 These overlaps exist

- between CQC GP practice requirements and GMC revalidation requirements

- between evidence sought by NHS England for contract compliance and CQC’s regulatory requirements

- between NHS England in its oversight role of the national performers list (NPL) and GMC’s regulation of GPs on the GP register

- between NHS England in its oversight of national contracts and ICBs in their oversight of local contracts and accountability for system performance

1.5.3 NHS England, CQC and GMC already work closely together to share data but there is more work to be done to align our processes and minimise the workload for general practice.

5.6 The ambition being delivered

NHS England, CQC and GMC are committed to;

- identifying immediate actions to support GPs and GP practices to reduce the workload associated with regulation

- align and streamline regulatory and commissioning processes taking a more targeted and risk-based approach to regulation and contract management

- improved information gathering and intelligence about services – we need to ensure that the data and information we identify to collect, measure, and monitor, is clear and consistent, and proportionate to risk

- making it easier for commissioners and regulators to access and use shared information about quality, giving GPs time to focus on improving quality of care at the frontline.

Part B – general contract management

1 Contracts described

1.1 Comparison of contract types

1.1.1 Throughout this document there are many references to standard contracts General Medical Services (GMS), Personal Medical Services (PMS) and Alternative Provider Medical Services (APMS). In addition to the statutory provisions regarding eligibility in 1.2, 1.3 and 1.4 below, the following table provides a quick comparator between the 3 contract types:

|

|

GMS contract |

PMS agreement |

APMS contract |

|

Is the contract time limited? |

No Except in certain circumstances when a temporary GMS contract (see 1.1.2) can be used – see urgent contracts below |

Yes Note that a PMS contractor providing essential services may apply for a GMS contract any time prior to the end of the PMS agreement |

Yes |

|

Can the commissioner terminate at will? |

No |

Yes |

If agreed by the parties and contained within the contract |

|

Must the contractor provide essential services? |

Yes |

No |

No |

|

Is there a standard form contract? |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Does the standard form contract contain key performance indicators (KPIs)? |

No |

No |

No |

|

Can KPIs be added? |

KPIs can be agreed between the parties in relation to supplementary quality-based services |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Payment arrangements | GMS statement of financial entitlement directions(SFE) |

As agreed by the parties and contained within the agreement – there may be reference to the GMS SFE |

As agreed by the parties and contained within the contract |

1.1.2 Following the termination of a GMS contract, NHS England and integrated care boards (ICBs) have the authority, as per regulation 16(2) of the GMS regulations, to enter into a temporary GMS contract with a contractor. This contract allows the provision of primary medical services to the former patients of the terminated contractor for a maximum period of 12 months. The purpose of this temporary contract is to allow sufficient time for a competitive tendering exercise to be conducted, enabling the establishment of a new contract.

1.1.3 While it is preferable, commissioners are advised against entering into a temporary GMS contract due to the associated risks. The APMS contract is typically commissioned for a predetermined period of time, and competing providers would have understood that the contract would only be awarded to the successful provider for a specific duration. Consequently, the market expects that there will be an opportunity to compete for the contract at some point. Merging with a GMS contract would eliminate that possibility.

1.2 Statutory provisions: persons eligible to enter into GMS contracts

1.2.1 By virtue of the delegation agreement, all references in legislation should be assumed to apply also to ‘the commissioner’.

1.2.2 Section 86 of the NHS Act sets out the types of persons (including organisation types) that may enter into a GMS contract.

- In Section 86: “health care professional”, “NHS employee”, “section 92 employee”, “section 107 employee”, “section 50 employee”, “section 64 employee”, “section 17C employee” and “Article 15B employee” have the meaning given by section 93.

1.2.3 GMS regulations, part 2, regulations 4 to 6 set out the eligibility criteria that must be satisfied before any of the types of persons set out in section 86 of the NHS Act can enter into the GMS contract.

1.3 Statutory provisions: persons eligible to enter into a PMS agreement

1.3.1 By virtue of the delegation agreement, all references in legislation should be assumed to apply also to ‘the commissioner’.

1.3.2 Section 93 of the NHS Act sets out the types of persons (including organisation types) that may enter into a PMS agreement (referred to in the Act as 3ection 92 agreements).

- In Section 93: “health care professional”, “NHS employee”, “section 92 employee”, “section 107 employee”, “section 50 employee”, “section 64 employee”, “section 17C employee” and “Article 15B employee” have the meaning given in this section.

1.3.3 PMS regulations, part 2, regulations 4 and 5 set out the eligibility criteria that must be satisfied before any of the types of persons set out in Section 93 of the NHS Act can enter into the PMS agreement.

Note: where 2 or more persons operate their practice as a partnership, the PMS agreement is not treated as being made with that partnership rather the persons agree to contract together as ‘the contractor’.

1.4 Statutory provisions: persons eligible to enter into an APMS contract

1.4.1 By virtue of the delegation agreement, all references in legislation should be assumed to apply also to ‘the commissioner’.

1.4.2 The NHS Act does not list persons who may (or may not) enter into an APMS contract.

1.4.3 The APMS directions 4 and 5 contain provisions relating to circumstances in which certain types of persons or organisation may not enter into an APMS contract. Provided direction 5 does not apply, any person or organisation may enter into an APMS contract.

1.5 Urgent contracts

1.5.1 Circumstances may arise that require the commissioner to put in place an urgent contract. Such circumstances may include:

the death of a contractor

the bankruptcy or insolvency of a contractor

termination of an existing contract due to patient safety

1.5.2 Where continuity of services to patients is required, the short timescales involved may not allow the commissioner to undertake a managed closedown and transfer to a new provider (details of which are set out in the chapters on planned and unplanned practice closedown). Additional information can also be found in the unplanned closures chapter. The commissioner may therefore, look to award a contract to a specific party that is able to provide the services to patients at short notice.

1.5.3 Prior to awarding a contract in this scenario, the commissioner should consider a number of factors that are set out in the paragraphs below.

Procurement

1.5.4 Commissioners should defer to the published statutory guidance on the provider selection regime (PSR). The urgent provisions within the regime may apply to secure immediate needs, eg to establish caretaker arrangements. However, as this will be a temporary arrangement it must be reconsidered after a set period. The statutory guidance provides further information about proper application.

Premises

1.5.5 The previous contractor may own or lease the premises which, as a result, may not be available for the provision of the services under a new contract. The availability of the premises must be ascertained before entering into a temporary contract.

Primary care networks

1.5.6 The commissioner should facilitate a discussion between the incoming contractor and the primary care network (PCN) to which the outgoing contractor was a member, involving the relevant local medical committee (LMC), with the expectation that PCN membership should be maintained in order to ensure that patients continue to receive uninterrupted network services.

1.5.7 If the contractor is still not willing to join the PCN then the commissioner will work with the existing PCN core network practices (GP practices who signed up to and are responsible for delivering the requirements of the network) to ensure continuity of services to its registered patients.

1.5.8 If the PCN is not prepared to accept the contractor as a member, the commissioner may require a PCN to include the practice as a core network practice of that PCN. Where the commissioner is minded to require a PCN to do so, the commissioner must engage with the relevant LMC and, when making its determination, have regards to the views of the LMC. Section 4.6 of the Network Contract DES 2021/22 – PCN requirements and entitlements sets out the process for allocating a practice to a PCN.

1.6 Public involvement

1.6.1 One of the general duties of commissioners is to ensure there is public involvement where a decision leads to an impact on the provision of primary care services. If under a new contract, services are provided from a different location, this will be an impact on the services which may trigger the need to undertake a public involvement exercise.

1.6.2 Where there is no time for undertaking an exercise prior to entering into the contract, the commissioner should ensure that as soon as possible after the contract is entered into, it arranges for such an exercise to be undertaken prior to the commissioner making any decisions about the long-term provision of services.

Commissioner standing orders (SOs) and standing financial instructions (SFIs)

1.6.3 The commissioner may have organisational standing orders and standing financial instructions that require contracts to be procured in certain ways, eg securing three quotes for contracts up to a certain financial value. Where time does not allow the rules to be followed, there may be an emergency process that must be followed.

Other factors

1.6.4 Further factors may be relevant depending on the circumstances of the matter. Please refer to the chapters on planned and unplanned practice closures for a list of all factors that may be relevant.

1.6.5 Commissioners should also consider that if a practice has closed because of concerns in relation to patient safety, the incoming provider may need to be commissioned to undertake a review of systems and processes. This should include but is not limited to, undertaking audits to provide assurance around patient safety. This recognises the additional work that commissioners may need to reflect in the contract to provide assurance with regard to patient safety and public confidence.

Which contract form?

1.6.6 A GMS contract can be used where the commissioner has terminated a contract of another provider of primary medical services, and as a result of that termination, it wishes to enter into a temporary contract for a period specified in the contract for the provision of services.

1.6.7 A time limited PMS agreement may not be attractive in this scenario as the PMS contractor, if providing essential services, can request a non-time limited GMS contract at any time.

1.6.8 It is common for APMS contracts to be used in such a scenario due to the flexibility of:

types of organisations that can enter into APMS contracts

flexibility of types of services and payment mechanism that can be agreed

flexibility around duration and termination provisions

1.6.9 The commissioner should therefore consider what services and duration is required and whether there are any restrictions on the proposed contractor entering into different contract types to meet local diverse health needs.

1.7 Primary care support services notifications